‘He mirrors us.’ Tongva artists see the Indigenous story in the tragedy of P-22

- Share via

When Los Angeles’ most celebrated mountain lion, known as P-22, was euthanized Saturday, his passing prompted headlines across the country, accolades from prominent politicians and a memorial hike in honor of what one congressman called “our beloved mascot.”

But perhaps the most heartfelt tribute came from representatives of the Tongva, Los Angeles’ first people, who feel, like P-22, displaced from their own land.

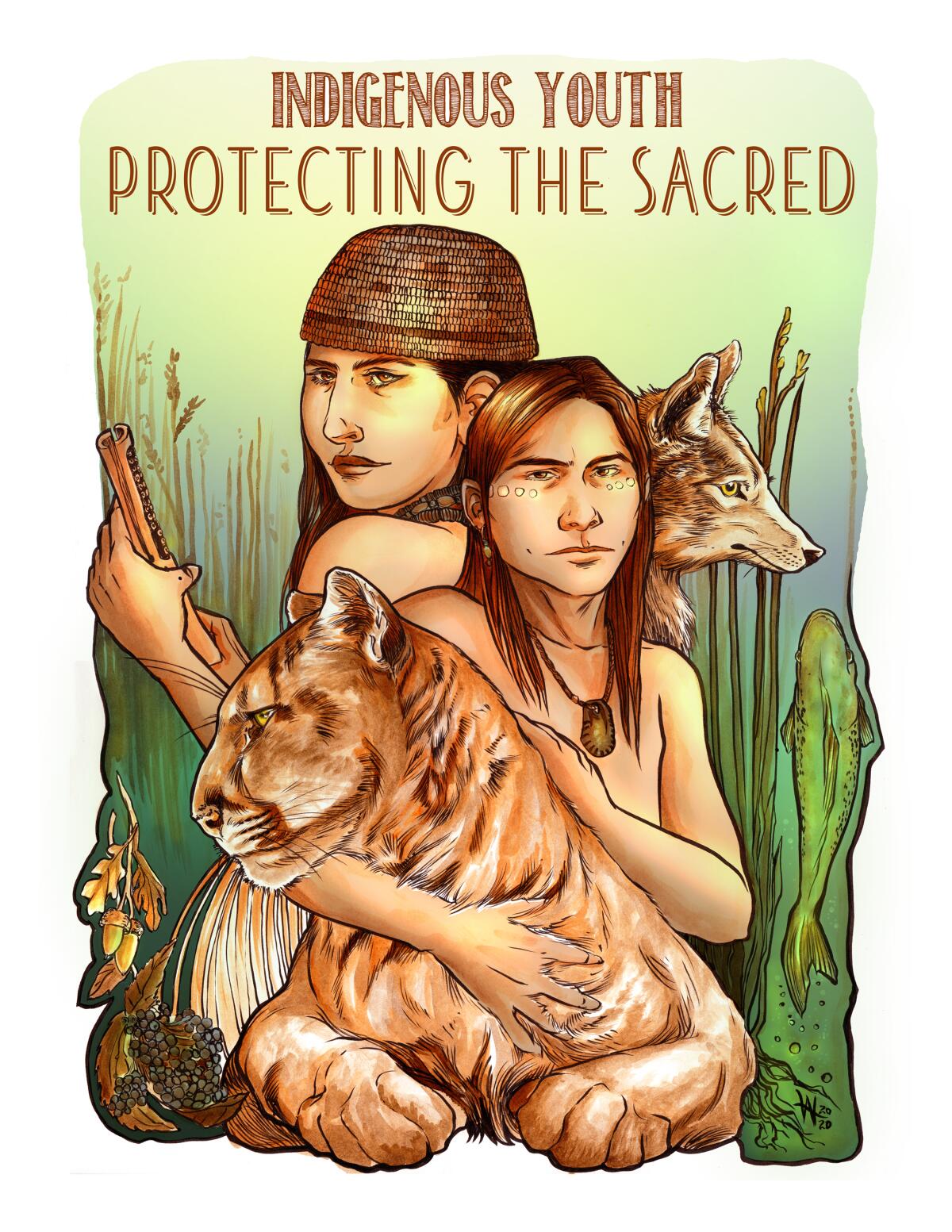

Tongva artist Weshoyot Alvitre posted on Instagram a montage this week of photos of the mountain lion accompanied by a song she sang in the Tongva language to the celebrity cat, “to send you back, in our language, so you’re not stuck in this world after all the suffering you endured.”

The post drew more than 1,500 likes and several comments.

For Alvitre and fellow Tongva artist Mercedes Dorame, the death of the mountain lion hit particularly hard because the cat’s story of displacement reflects that of their own people.

“He mirrors us,” Alvitre wrote in a poem posted on Instagram about the cougar. “He was born on this land, like those who came before him. I’m angry and saddened he won’t have a chance to return to the land in the way he should.”

The Tongva, Los Angeles’ first people, lived in Southern California for thousands of years before Spanish, Mexican and white American settlers destroyed their villages and subjugated them. In October, they received a one-acre parcel from an Altadena homeowner, establishing Tongva tribal land for the first time in nearly 200 years.

The parcel, like P-22’s hunting grounds around Griffith Park, is squeezed by suburban sprawl.

Wildlife authorities say the mountain lion suffered from a series of ailments — including old age — and was likely hit by a car in recent weeks, which may have explained his recent interactions with humans and their pets.

Alvitre noted that cars like the one that probably hit P-22 are traveling freeways built over Tongva trade routes and atop traditional burial sites.

“Colonization has affected the land and the health of the land and the health of everything that relies on the land,” she said.

The Tongva people have a special relationship with animals.

“We don’t place ourselves above them; we consider them our relatives,” Alvite said. “And when we see them suffering, it’s really a reflection of us suffering.”

And many of us will meet an untimely death, with direct contributions from all these triggers effecting our minds, our bodies and our spirits. Most of us will not achieve our full quality of life because of where humanity has darted us, and taken us, drugged on stretchers. He mirrors us. He was born on this land, like those who came before him.

— Weshoyot Alvitre, Tongva artist, via Instagram

Both Alvitre and Dorame said the “wildlife overpass” above the 101 Freeway in Agoura Hills being created for cats like P-22 is necessary but is an insufficient step in addressing how the built environment has displaced wildlife and distanced people from nature.

Indigenous animals and humans have a connection to the Los Angeles basin, Dorame said.

“You can’t isolate the individual from the land, you can’t isolate a community from its base,” she said.

She was troubled by P-22’s celebrity status, which she said reduced the cat to a “scintillating, sparkling specimen,” and overshadowed the tragedy of the big cat’s habitat in decline.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.