Racist audio leak raises a tough question: Why don’t Latinos vote more in L.A.?

- Share via

Florentina Serna has waited more than three decades to cast a ballot. She still can’t. When election day comes around and she sees the propositions and candidates and knows she can’t do a thing to help change her hometown, she feels powerless.

Her daughter, Maria Serna, can vote but rarely exercises the right her 55-year-old mother covets. It’s a circumstance that frustrates Florentina — and anyone who runs for office in the city of Los Angeles.

“She’s on top of us about it, me and my sister,” Maria, 37, said sheepishly as she stood outside a supermarket in the family’s Arleta neighborhood. Florentina is waiting for her naturalization ceremony to be scheduled so she can register to vote.

“Es importante votar, porque es importante el cambio,” Florentina said. “It’s important to vote, because change is important.”

Nearly a million Angelenos turned out to vote in the most recent mayoral election, a significant increase from the roughly 401,000 who cast ballots in 2013 when Eric Garcetti was first elected mayor. But while the total number of voters increased significantly across all demographic groups, the share of the electorate that was Latino did not. Latinos’ share of votes cast was no larger this year than nine years ago.

White voters make up less than 30% of the city’s residents but were by far the largest portion of those who cast ballots in this year’s election — nearly 60%. Latinos make up about half the city’s population and about 35% of eligible voters but constituted less than a quarter of those who turned out, according to Political Data Inc., a campaign consulting firm whose numbers are widely relied on by political figures in the state.

In part because of that relatively low voter turnout, Latinos’ representation in local elected office lags far behind their numbers.

The gap between population and power lies at the heart of the political scandal that shook Los Angeles this fall — the leaked recording of a meeting in which Nury Martinez, the now-disgraced former City Council president, and two of her colleagues complained — in racist, vulgar language — about the underwhelming state of Latino political power. At the time, Latinos held only four of the 15 City Council seats.

Latinos don’t vote for many of the same reasons people in general don’t go to the polls — feeling that candidates don’t represent their views or that their ballot won’t count, for example.

Other crucial circumstances hamper voting among Latinos more than some other segments of the population, however: A younger electorate. Immigration status. Greater distrust of the political system, an artifact of life in troubled home countries. A lack of voting history in the U.S.

“Sometimes the case for voting is harder to make with some Latino voters because of the lack of representation and the history of marginalization,” said Mindy Romero, director of the Center for Inclusive Democracy at USC. “There’s typically less outreach in Latino communities overall, with great exceptions in L.A. But the overall system usually is connecting with Latinos less. And when they are connecting, sometimes those connections are not effective.”

In the race for mayor, businessman Rick Caruso bet big on Latinos and lost.

He spent a little more than $2 million on Latino-focused radio and television ads during the primary, knocked on doors and held town halls in South Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley. He showed up at restaurants known for being community hubs, such as La Flor Blanca Salvadoreña near USC and La Chispa de Oro in Boyle Heights, northeast of downtown.

“The plan to win was predicated on Latinos — and for that I do think that the polling showed payoffs,” said Sonja Diaz, founding director of the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute. “Ultimately it’s not enough to overcome structural discrepancies in voter behavior in this country, whereby more mature, whiter voters continue to outperform their share of the electorate.”

A bombshell recording has thrown L.A. politics into chaos. What was really being discussed? L.A. Times reporters and columnists pick it apart, line by line.

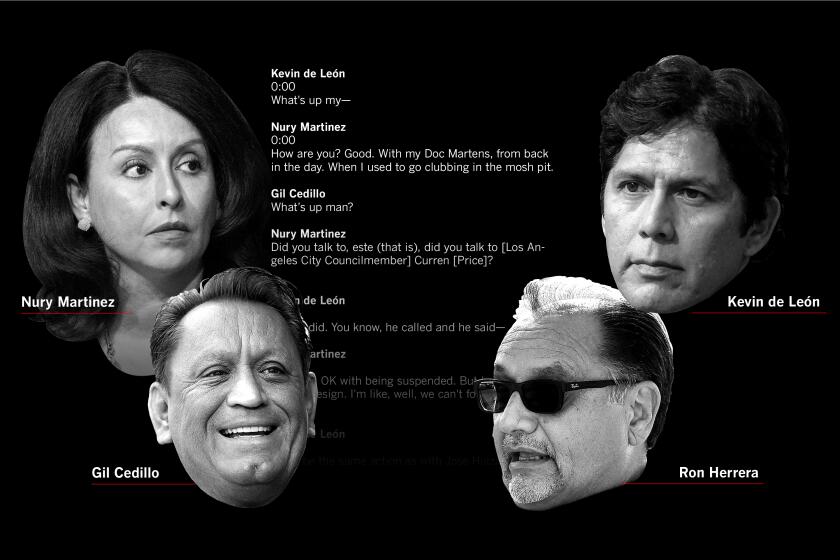

The audio leak controversy, first reported by The Times, centered on a conversation about redistricting, the once-a-decade process of drawing new boundary lines for each council district. Then-Councilmembers Martinez and Gil Cedillo and Councilmember Kevin de León discussed the need to preserve and expand Latino political power while ensuring that they and their allies would have districts that help them win reelection.

The recording captured the three politicians and Ron Herrera, then head of the L.A. County Federation of Labor, as they obsessed, not over Latino outreach or turnout, but over ways to design council districts that would be favorable to their allies — and not so favorable to their rivals.

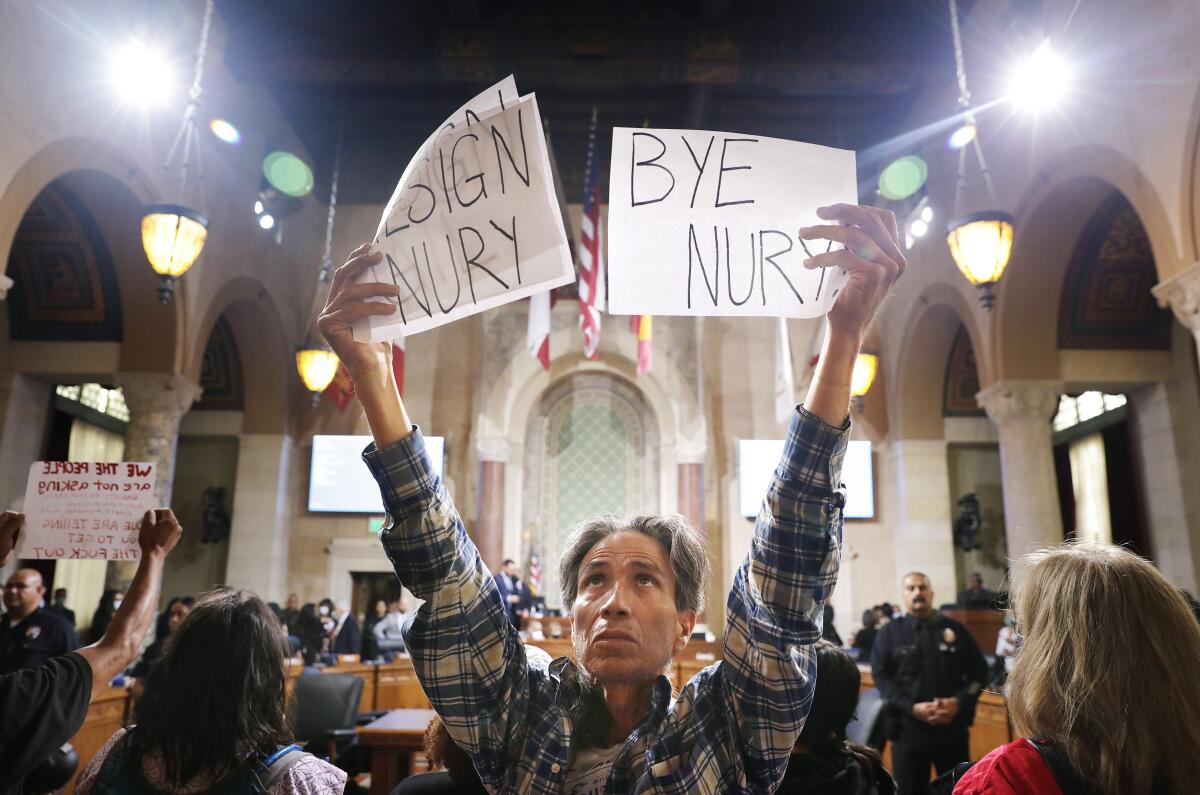

Martinez and Herrera resigned in the wake of the scandal. Cedillo, whose term ended this month, and De León did not.

In a three-page letter after the scandal broke titled “Why I Did Not Resign,” Cedillo argued that, while the conversation “crossed a line at several points,” ultimately he and his colleagues were just doing their jobs and working to ensure Latinos were fairly represented in the redistricting process.

“Since our conversation, the redistricting process has played out, and new Council districts were set,” he wrote. “Did Latinos get a fair share of representation based on the percentage of our population? No, we didn’t!”

Former L.A. City Councilmember Gil Cedillo has written a public letter addressing his refusal to resign from the council in the wake of his involvement in a leaked audio recording that included racist comments.

But to some community organizers, the politicos’ leaked conversation came across as a self-centered enterprise, a way to consolidate their own power rather than increase Latino representation and make it stronger.

“For me, when they were talking about Latino power, it was really a facade for their own political power and their own political circles, not necessarily the needs of the people,” said Ivette Alé-Ferlito, executive director of La Defensa. Alé-Ferlito co-founded the group with Eunisses Hernandez, who unseated Cedillo.

“When you become too disconnected from what’s happening on the ground, and you’re more interested in maintaining your own political power, then you’re really not doing your community a service, and in fact you’re using your community.”

::

Across the U.S., voting has historically been more challenging for every group except white men.

The 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1870, granted men who were citizens the right to vote regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Still, the right to vote remained a white, male privilege for decades.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, a legacy of the Civil Rights movement, broke down many barriers for the Black community. It outlawed racial discrimination in voting and required federal approval of election procedures in states that barred Black people from the polls.

It wasn’t until 1975 that Congress expanded the Voting Rights Act to require that certain jurisdictions provide language assistance to individuals who have limited English proficiency.

While Black voter participation has improved, Latino and Asian American turnout continues to lag.

Lydia Camarillo, president of the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, pointed to differences in cultural attitudes toward voting among demographic groups. Black voters, she said, “talk about why you should vote at the churches, they talk about how people died to make sure that they vote. They have a different history.”

For Latinos, she said, how long their family has been in the U.S. can influence voting behavior. “If you’re a native born, second, third, fourth generation … do people in your family vote? Is there a history, or are you the first person starting that historical trend of voting?”

And then, Camarillo said, “depending on what country [Latinos] come from, that’s also another variable.”

Ruben Lopez, a Panorama City resident, said that he wants to contribute to the community and to society but that, “in my humble opinion, everything is corrupt.” Lopez, who will be a U.S. citizen soon, said he shaped his perspective growing up in Peru.

He had no difficulty pointing to current examples in his home country. This month, President Pedro Castillo was impeached hours after he tried to dissolve Congress, a move denounced by lawmakers as an attempted coup.

Castillo’s successor, former Vice President Dina Boluarte, is the country’s sixth president in about as many years.

::

Jorge Carballo, 21, has voted once in his life, during the 2020 presidential election. A friend, who is more politically engaged, persuaded him to mail in his ballot. He didn’t vote in November.

Carballo emigrated to L.A. from Mexico when he was 6. He said politics were “never much of a talking point in the home.” His dad can’t vote; his mom can, but doesn’t.

“For Latinos, it’s never really been a household thing,” the Sylmar resident said. “They kind of just brush it to the side.”

In California, nearly 4.7 million people — 12% of the population — live with a family member who is in the country illegally, according to a 2017 report by the Center for American Progress, a Democratic-oriented policy institute. Of those, 42% are children younger than 18.

“You have household formations whereby it’s the younger people that are aging into the electorate, but maybe in a household where the adults aren’t able to cast a ballot,” said Diaz, of UCLA. “That’s different than the citizenship practices of this country that have afforded white people access to the ballot box.”

Francisco Robledo emigrated to the U.S. from the Mexican state of Jalisco when he was in his early 20s. Decades passed before he became a U.S. citizen and started voting.

He raised two sons on his own after his wife died. Busy with work, he spent his free time teaching them to stay away from drugs and violence. Unable to vote, he didn’t talk to them about politics.

Robledo, now 78, has been a regular voter since 2004. His sons, now in their early 30s, don’t vote.

“I tell them to vote, but they ignore me,” he said, as he sat in a Pacoima laundromat. “I tell them they have to vote for their futures, for that of their kids.”

His sons are evidence of another factor that puts a damper on the Latino vote. Both the Latino and Asian American electorate trend younger — and younger Americans don’t vote at the same rates as those who are older.

The median age of eligible Latino voters is 39, nine years younger than the median age of all adult eligible voters, according to the Pew Research Center. Only about 30% of Latino eligible voters are 50 or older, compared with nearly half of all eligible U.S. voters.

In the most recent mayoral election, Angelenos ages 18 to 34 represented 23% of total votes cast, compared to 28% of votes that came from those over the age of 64, according to Political Data, Inc. That gap had narrowed significantly from the 2013 mayoral election, when younger voters were only 11% of votes cast and 34% of votes came from those 65 and older.

“People say: ‘Oh, Latinos are immigrants, Asians are immigrants and that’s why they can’t vote.’ That’s not it. We’re young,” Diaz said. “Latinos and Asian Americans are not different than other Americans, they’re young Americans who don’t go into the franchise.”

Robledo voted in the mayoral election, casting his ballot for Caruso.

“I vote and it feels like my vote counts for something,” he said. “And the more of us who vote, it’s better.”

::

In Los Angeles, Latinos have historically been underrepresented in positions of power.

Since California became a state in 1850, Los Angeles has had 43 mayors. Only four have been Latino. In addition, the city had one Latino acting mayor who served for less than two weeks. Today, Latinos occupy a little more than a quarter of the City Council seats.

“Latinos are not represented commensurate with their population numbers,” Romero said. “It matters for policy; it matters for real outcomes in communities.”

Romero pointed out a “vicious cycle” in which greater representation at the ballot box could help bring about more representation on the City Council for Latinos, “but at the same time many potential Latino voters look to the council and don’t see as strong a representation as they would like, and that sometimes can discourage.”

When Antonio Villaraigosa won election in 2005, he became the city’s first Latino mayor in more than a century. His election was national news, landing him on the cover of Newsweek magazine with the headline, “Latino Power ... How Hispanics Will Change American Politics.”

In the lead-up to that election, Camarillo helped mobilize Latinos through the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project. The nonprofit, she said, spent a million dollars on billboards, TV ads, registration drives, canvassers and phone banks to turnout Latino voters.

SVREP called voters and asked if they wanted to mobilize their neighborhoods. Hundreds turned up to volunteer and contact their precincts, Camarillo said.

“It was going to be a moment of history if Villaraigosa was elected …. and Latinos were very much energized,” Camarillo said.

In a recent interview with the Times, Villaraigosa said he didn’t think Latinos voted for him only because he would be the first in a century, but because “people saw me as a fighter.”

“I think they voted for me because I had come out of the movement, and I had been somebody that always stood up for immigrants,” he said.

He stressed that Latino participation in the political process “is key to elected officials adequately representing everyone, ‘cause they won’t if we don’t participate.”

“I think at the end of the day, we have a lot of work to do,” he said. “We can’t just focus on the Latino vote during election time. We’ve got to focus on the entire Latino community. We’ve got to do it in between elections.”

Political Data Inc. found that a little more than 220,000 Latinos turned out for the recent mayoral election, a huge jump from the 93,432 who voted in 2013. But the same share of Latinos cast ballots as did nine years ago: 23%.

“In terms of the numbers, this isn’t the progress that people would want to see,” Romero said. But, she stressed, “people should not take these numbers and think that the Latino vote can’t be mobilized or that there hasn’t been good work that’s been done.

“What this emphasizes is just how challenging it is and how much work still needs to be done and how much resources still need to be deployed in Latino communities to help increase participation,” she said.

::

In Lincoln Heights, Maria Contreras and Genaro Oceguera are a couple split when it comes to voter participation.

Both emigrated from Mexico and are now U.S. citizens. Contreras has made it a point to vote over the last six years, including in local elections. Asked on a recent afternoon why she felt it was important, she pointed to a nearby street corner where a gray sofa bed and white dresser drawers had been dumped.

“We need people who really want to help the community,” she said from her front porch. In the recent election, she cast her vote for Caruso, “because he speaks Spanish and supports the community.” She relied on her son to help her fill out the ballot.

Her husband doesn’t vote. He tried to vote for the first time in 2020 for then-President Trump. But his ballot was returned to him without being counted, apparently because of an issue with his signature on the document.

After that, he said, he grew distrustful. And, he said, he feels unsure of how the voting process works. He didn’t cast his ballot in November.

“I don’t know how to vote,” Oceguera said as he kept an eye on their year-old grandson toddling outside their blue house. “If I learned more, I think I’d vote.”

“A lot of us don’t know how to vote, and there’s not enough information,” Contreras chimed in.

Groups such as InnerCity Struggle, based in the Eastside, are trying to help.

Around election time, members go door knocking in the community, reach out via text, place advertisements in local media and use social media to encourage voters to turn out.

With more funding, interim Executive Director Henry Perez said, the nonprofit would be able to expand its efforts year-round and hire larger voter-outreach teams.

Perez bemoaned the fact that candidates and campaigns tend to focus their resources on regular and high propensity voters. Meanwhile, Latino voters, he said, are “perceived to be low propensity voters.”

“Basically you are in a way fulfilling the destiny that these voters don’t vote. If there’s not investments in reaching out to them and contacting them and speaking to them, then these voters will not have the information necessary for them to vote,” Perez said.

Said Diaz, with UCLA: “If the campaigns and candidates continue to exclude and mark Latino and Asian American voters at the periphery, both in terms of how they spend, who gets to be a strategist, who gets to be a candidate, then the least that those elected and appointed can do is the voter education.”

::

Jasmin Hernandez was among the more than 200,000 Latinos who voted in the most recent mayoral election.

The 25-year-old studied both Bass and Caruso closely. Her family had been pushed out of Echo Park and into the San Fernando Valley because of gentrification, she said, and “to me, it was just important to see that more of that wasn’t going to happen.”

Ultimately, she cast her ballot for Bass, expressing concerns that Caruso was being funded by people who might further displace community members.

Hernandez learned about voting when she was 15, after her dad — an immigrant from El Salvador — became a citizen. She still has her dad’s first “I voted” sticker plastered to the dashboard of her car.

“He made it a very big deal about the fact that in this country you have a voice and you have a choice to choose the people you want to see up there,” she said. “Being first generation Latina, we don’t get much of a voice anywhere.

“So it’s nice to know that at least in some place, some aspects, I could have a say in who is going to be running things around me.”

Times staff writers Benjamin Oreskes and Nathan Solis contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.