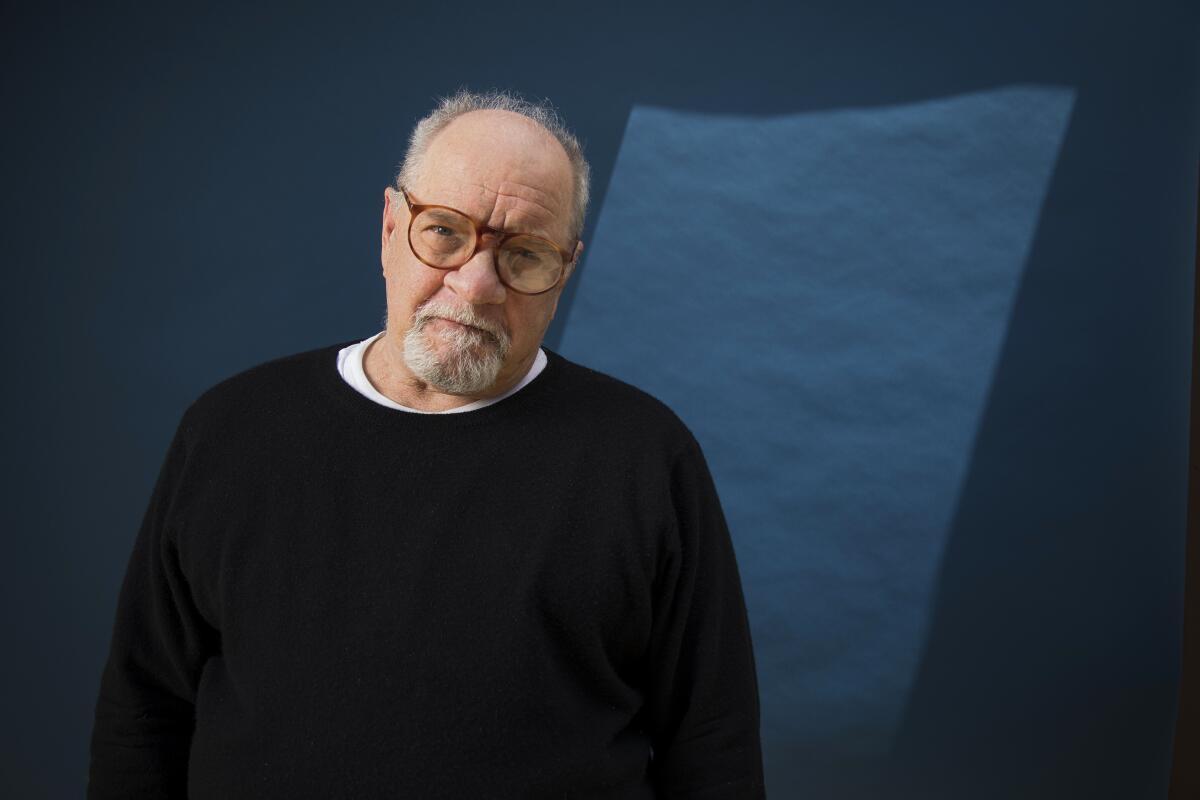

How Paul Schrader deals with a national stain in ‘The Card Counter’

- Share via

In a sense, Paul Schrader is alone in his room, making movies about a man alone in his room, both immersed in their professions and drawn alongside larger issues.

“I’ve gone back to it four or five times, indirectly other times,” says the writer of “Taxi Driver” and writer-director of “American Gigolo,” “Light Sleeper,” “First Reformed” and this year’s “The Card Counter” — all specimens of this cinematic category he embraces as his own.

“I stumbled on it with ‘Taxi Driver.’ It was transplanted from fiction; it really wasn’t a movie genre: the existential hero. It was out of European, 20th century fiction — Dostoevksy, Sartre, Camus. I discovered it was something I was good at; it was natural to me and other people weren’t doing it.”

He delightedly quotes a review of the new film that says he’s working in a genre of his own making: “It doesn’t get more complimentary than that.

“When you have idiosyncratic gifts, you think it’s the easiest thing in the world. Then you see people trying to copy ‘Taxi Driver’ and you think, ‘Well, it’s a lot harder than I thought,’” he says with a laugh. “You look at Preston Sturges and say, ‘That’s easy,’ and you try to do it and you say, ‘That’s hard.’”

“The Card Counter” finds that lone man played by Oscar Isaac; his rooms are hotel accommodations made more faceless by his own idiosyncrasies (such as wrapping the furniture in blank cloth). The former Marine now called William Tell has, since his release from prison, become a quiet, methodical poker player mechanically executing gambits, controlling his environment. Eventually relationships develop (with characters played by Tiffany Haddish and Tye Sheridan) that shake him from his doldrums and force him to confront a past he long ago deemed unforgivable.

“What could he have done that he can’t forgive himself for?” Schrader ponders. “Even serial killers and Ponzi-scheme guys have justifications. Then I thought of Abu Ghraib — to besmirch the image of your nation. You’ll die and everyone else will die, and that stain will remain. There’s nothing you can do about it; it will always be a stain on your country and you put it there.”

In “The Card Counter,” there is a showboating, star-spangled gambler, Mr. U.S.A., who’s from Ukraine. The protagonist is called Bill, and there’s a hefty one coming due, and of course a Tell is any poker player’s Achilles heel. The emptiness of routine is a defining characteristic of this world: Bill’s rote existence is his flatly played profession, a kind of background thrum like the Zen of repeating a task until the task disappears.

“He’s waiting,” says the writer-director. “He doesn’t have the courage to die or the will to live. He’s in a limbo of unforgiveness. Society has forgiven him, but he hasn’t.”

The writer paraphrases a bit of Bill’s emotionless narration:

“‘Poker is just about waiting. You wait hand after hand after hand, then it happens. That magical hand happens once a day or every two days, when two players are convinced they’re going to win and they both go all in. Until then, you’re just passing the time.’”

Schrader says, “The line that I wrote relatively unknowingly in ‘Taxi Driver’ is one that comes back. Travis [Bickle, of that film] writes in his journal, ‘Every day is like the day before. The hours pass, the years pass. And then there is a change.’ I wrote that in 1972 and I’m still writing that.”

Perhaps surprisingly, it wasn’t the opprobrium of Abu Ghraib that served as the film’s seed.

“I was watching poker players on TV and thinking about people who sit hour upon hour in the casinos. Today with slot machines, you don’t even have to put money in, you don’t have to pull the lever. You just sit there and life flows past you. It must be somebody who thinks this is a simulacrum for life itself.

“People think it started with Abu Ghraib. No, it started with the metaphor of what kind of person counts cards, plays poker 10, 12 hours a day, six, seven days a week. When you can find something original about that occupation —”

And the auteur is back into the guts of his genre:

“Everyone knew what a taxi driver was — he was the best friend of the protagonist who cracked jokes and sat in the front seat while the romantic couple sat in the back. When I looked at him, I saw the black heart of existential dread. I saw a kid locked in a yellow box, floating through the sewers, completely alone and angry.

“When you find a new way into an occupation, it makes the viewer think of it in a different way. That’s not how I thought of playing professional cards; that’s not how I thought of being a taxi driver. That’s not how I thought of being a drug dealer [in ‘Light Sleeper’]. I didn’t know being a drug dealer was essentially boredom,” he says with a laugh.

More to Read

Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.