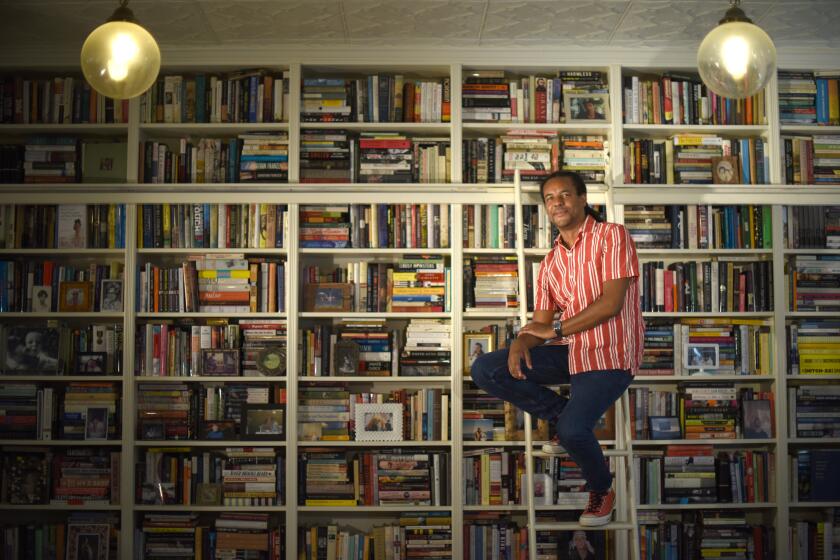

Colson Whitehead just wants to have fun

- Share via

On the Shelf

Harlem Shuffle

By Colson Whitehead

Doubleday: 336 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In Harlem during the summer of 1964, a white police officer shot and killed a Black 15-year-old boy in front of more than a dozen witnesses, setting off six nights of rioting across the neighborhood. “Cool It Baby,” one of three connected stories that make up Colson Whitehead’s new novel, “Harlem Shuffle,” opens in the aftermath of this eruption, when furniture dealer/fence Ray Carney receives a visit from his ne’er-do-well cousin Freddie. Clutching a briefcase full of misbegotten booty, Freddie recounts his experience trying to get a sandwich in the middle of the ruckus: “‘People running up and down, screaming. I’m like, damn, this riot stuff will cramp a brother’s style.’”

Social unrest, crackerjack scene-setting, a perfectly timed laugh: This is Whitehead distilled, in a way we haven’t seen in a while. “I like writing about American history and race, I like writing about the City, I like writing about pop culture, and I like telling jokes — but all those elements don’t always fit into this or that book,” he says, speaking on the phone from New York.

Whitehead started thinking about “Harlem Shuffle” in 2014, before writing his next two novels, 2016’s “The Underground Railroad” and 2019’s “The Nickel Boys” — serious books full of trauma and devastation that won unprecedented back-to-back Pulitzer Prizes. “There’s an element of fun that was missing in ‘Underground’ and ‘Nickel Boys,’ just ’cause of the subject matter. I like to use satire and dark humor.”

The adventures of Ray Carney are, in part, a creative reaction to Whitehead’s years of immersion in the horrific realities of slavery and Jim Crow. “[Carney]’s a Black man in 1960s Harlem, and that’s one of the things that defines him, but not one of the only things,” he says. Compared with the protagonists of his last two novels, Carney is “not subject to the same tragic pressures.” He’s “more free, not as controlled or determined by his environment — and he gets to win.”

Two miles north of Interstate 10, a cool breeze ruffles the overgrown grass around the Dozier School for Boys.

“Harlem Shuffle” is a spectacularly pleasurable read, and while it is, of course, literary, it’s also a pure, unapologetic crime-fiction page-turner. Whitehead has worked in this genre before, if less explicitly; his 1999 debut, “The Intuitionist,” was a speculative, postmodern detective story set in the nebulous world of New York City elevator inspection. He wrote that book after a previous novel failed to sell, to teach himself about plot and structure: “My model was film noir, but I was also diving deep into Elmore Leonard and Walter Mosley and James Ellroy. They were the people I was studying in terms of red herrings, revelations, withholding information and stuff like that.”

He cites a parallel set of forebears for his new book: lo-fi heist movies, Richard Stark (also known as Donald E. Westlake), Chester Himes and Patricia Highsmith. Stark’s Parker series — which follows a ruthless thief across 24 short, punchy novels — is the clearest influence. Whitehead sees “Harlem Shuffle” as “three novellas that come together Voltron-style to make a novel”: Each can stand alone, “but together, they gain power.”

Clocking in at just over 100 pages each, these interlocked narratives track Carney’s schemes, victories and misdeeds, as well as the changes in his life, in 1959, 1961 and 1964. With every section, “I’m pulling back more and more on Carney’s world,” Whitehead says. “We get introduced to the street-level crime in the first book. We pull back and get more of a sense of Harlem, and the corruption and the social structure — the hierarchy, the other forces working upon Carney and the other people in Harlem. And then we pull back and see the real power in the city.”

The through-line, and what keeps the author interested, is his study of Carney, “this very slow portraiture of this character.” Carney is not like Stark’s Parker (though Pepper, a vivid recurring character, very much is — a “terse professional … always being pulled down by the inevitable losers you have to associate with”). Carney considers himself “only slightly bent when it came to being crooked,” not a thief but a legitimate business owner who also operates as a fence: “There was a natural flow of goods in and out and through people’s lives, from here to there, a churn of property, and Ray Carney facilitated that churn,” Whitehead writes.

For ‘The Underground Railroad,’ about the harrowing escape from slavery, director Barry Jenkins took a novel step: hiring a mental health counselor.

“A fence is in between the straight world and the crooked world,” says the author, and that position — its duality and precarious nature — shapes Carney’s circumstances, movements and personality. Whitehead found inspiration in Highsmith’s Tom Ripley novels, “Ripley’s divided self. He’s homicidal, he’s queer, but never overtly expresses it, and the way his personality peeks out in the text was very interesting to me. Carney is not an unreliable narrator but he doesn’t admit to the truth he knows about himself. He doesn’t have to become a fence, he doesn’t have to keep being a fence. So why does he do it? He won’t admit why.”

Metaphorically speaking, Whitehead says, “Being a fence, in its in-betweenness, is particularly suited to the way I see things.” Many of his characters occupy unsettled middle spaces with fragile borders — between childhood and adulthood (“Sag Harbor”), freedom and captivity (“Underground,” “Nickel Boys”), life and zombie death (“Zone One”). “I sometimes make my protagonists into writers,” he says. He did this overtly in earlier books but, “Starting with ‘Sag Harbor,’ I found different ways to have people who are in but also without, the same way that writers are in the world but also stepping back a little bit to observe.”

“Sag Harbor,” a comedic autobiographical reflection on a teenager’s summer in the Hamptons, is almost entirely plotless. Its structure is as dissimilar to the propulsive heists of “Harlem Shuffle” as its tone is to the somber register of “The Nickel Boys.” “Different stories demand different tools, different ways of talking about the world,” says Whitehead. If fans of his Pulitzer winners can’t get behind a revelrous crime novel, he doesn’t care.

“Other people’s expectations aren’t really my problem, so I don’t think about them,” he says. “Changing up is part of my process, it’s how I work, and I’ve always realized that people come aboard and then get off at different stops. All I can do is the work that I find personally compelling.”

Right now, that work is a second Carney book, also in three parts, set in the 1970s. “I find the constraint of 110, 120 pages interesting to play with, and I have more things to say about Carney,” he says. Series characters are a staple of crime fiction but this is Whitehead’s first time writing so much as a sequel. “Having a character I enjoy this much and a world that still holds interest is new. It’s nice to know that I can do this for 20-something years and then have a new thing come into my life creatively.”

Could there be even more Carney books? “I can’t say,” he says. “I don’t feel obligated to do anything. If it’s not fun, I’ll just stop. If it’s not fun, I’ll do something else.”

Novelist Katie Kitamura on her latest novel, “Intimacies,” which follows an interpreter in The Hague grappling with complicity and a bad boyfriend.

Cha’s latest novel is “Your House Will Pay.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.