Why a novel about a home for ‘feeble-minded women’ resonates with our antiabortion moment

- Share via

On the Shelf

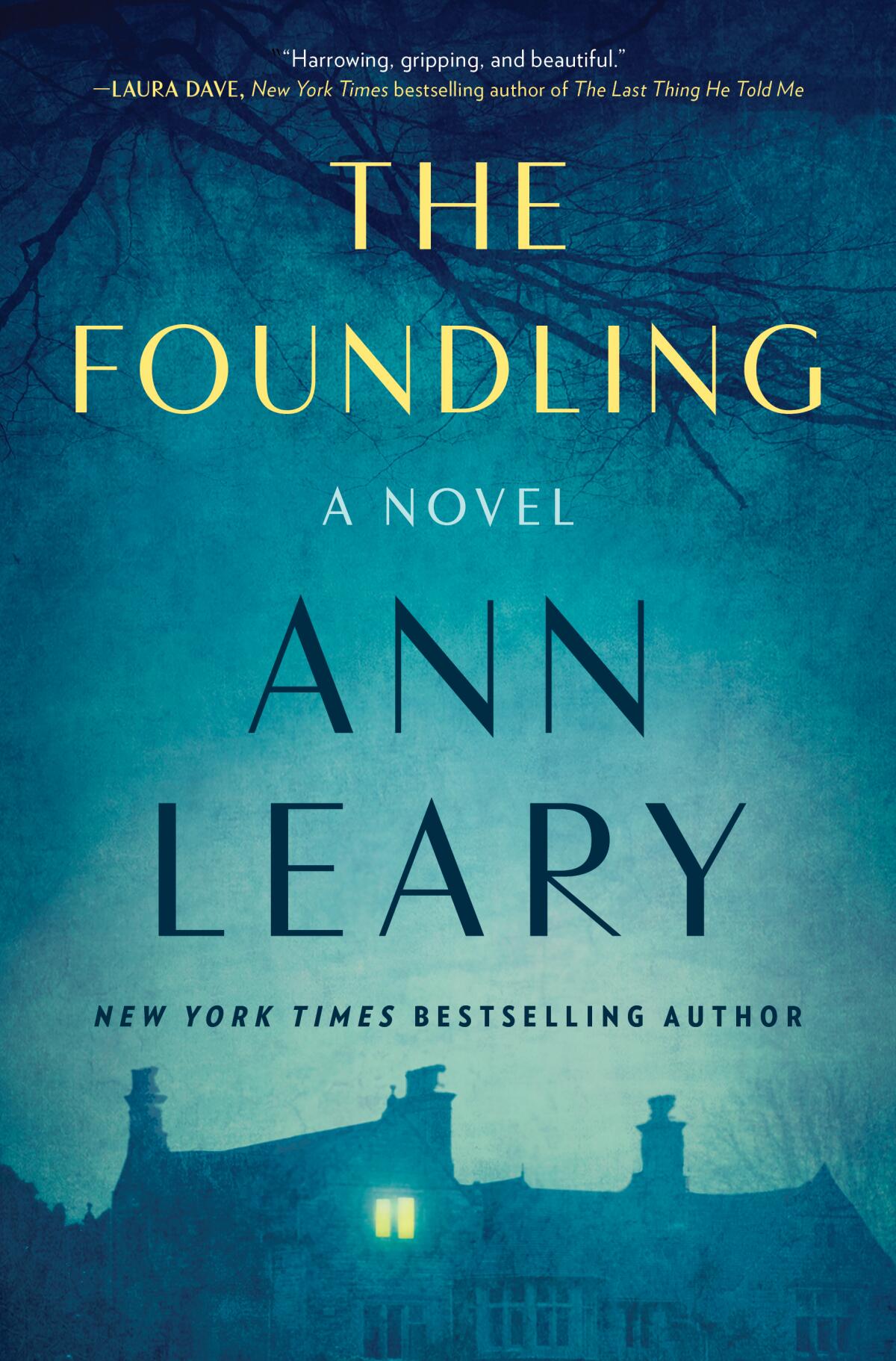

The Foundling

By Ann Leary

Scribner: 336 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The word “timely” is often used to describe novels that appear at a resonant historical moment. But when it comes to the regulation of women’s bodies and the criminalization of sex and reproductive practices, it’s hard to pick a time when a novel like Ann Leary’s “The Foundling” wouldn’t speak to where we are.

Leary, the bestselling author of three previous novels, sets her new one at the fictional Nettleton State Village. It is modeled on the historical institution of Laurelton State Village for Feeble-Minded Women of Childbearing Age, which operated in different forms between 1917 and 1998 in central Pennsylvania. As Leary discovered, it was not a benevolent group home for women with intellectual disabilities. Instead, it was a dumping ground for those deemed morally unworthy of giving birth.

Eugenics came to prominence in the United States in the early 20th century, promoted by social reformers as a way of controlling “undesirable” elements. Not surprisingly, many of these efforts focused on the bodies of women, employing theories closely tied to the pseudoscience of white racial superiority. (North Carolina, for instance, sponsored the forced sterilization of Black women until the 1970s.)

Laurelton warehoused women regarded as difficult daughters, troublesome wives and unwed mothers. For Leary, writing “The Foundling” was a way of exploring this nation’s history — but also the story of her own family. In a preface, she writes that her grandmother had worked at Laurelton as a stenographer from age 17, and while Leary’s novel follows various incarcerated women, its focus is on those who worked there and the tension within them between empathy and complicity.

Her protagonist, Mary Engle, lost her mother as an infant and was initially placed in an orphanage by her father. Later he sent her to live with an aunt, who led the young girl to feel she was forever a burden. At age 17, Mary is invited to a lecture by Dr. Agnes Vogel, one of the few female psychiatrists in 1927. Vogel’s research is on the “feeblemindedness” she believes is more prevalent among women.

A new film adaptation of a 2000 memoir, “Happening,” about a French woman’s illegal 1963 abortion, trades the book’s specifity for universal power.

“I trust you’re familiar with the type of girl I’m referring to,” she tells the audience. “You’ve seen her slinking in and out of bawdy houses and illegal drinking establishments … she may seem normal enough — in fact, she’s often quite pretty. Until you see her again, a few years later, ruined and destitute, begging for handouts, surrounded by her own diseased and illegitimate children.”

Vogel argues that these women are vulnerable to unscrupulous men who take advantage of their limited intellects — although it becomes clear that the only “proof” of such deficits lies in their refusal to adhere to social norms of temperance and marriage. Vogel insists that the compassionate solution is to confine these women in the village compound, where her staff offers the best of care, recreational activities and the benefits of honest labor (through which the women earn their keep).

Vogel needs a secretary, and Mary signs on. For the younger woman, Vogel represents a new ideal, a type of woman she has previously not known to exist. An accredited psychiatrist at a time when women were largely excluded from medical school, she is a figure of aspiration. But what Mary fails to apprehend is that the doctor elevates genetic legacy over the transformative power of education. During a discussion of religion, she tells Mary:

“It’s what you’ve been taught, but it’s not who you are. Who you were when you were born, who your parents were, where they came from, your stock and lineage are what determines who you really are, and who you’re going to be.”

Entranced by Vogel, Mary defends her from criticism by those who question whether the incarcerated women are truly “feebleminded” and worry they are being mistreated. Mary initially doubts such stories, but over time, she witnesses unsettling incidents. While publicly advocating temperance, Vogel strikes a shady deal to acquire the liquor she serves to wealthy donors. When an inmate hired out to serve as a maid is assaulted in her employer’s house, Vogel chooses not to report the crime.

Leary does a brilliant job of showing how the need for emotional attachment — in this case triggered by Mary’s upbringing — can cloud a person’s judgment. How, in other words, fear and neglect, rather than the waywardness Vogel rails against, are what really enfeeble the mind. Nothing is more painful for Mary than letting go of her ideal. But she must, and she does.

Bethanne Patrick’s May highlights include new fiction by John Waters, Chris Bohjalian and Emma Straub, fresh David Sedaris, breakout poetry and more.

“When [Dr. Vogel] released my hand, I caught my breath because I had a sudden sense of falling, the way one does in a dream, and the blood rushed straight to my heart,” Mary thinks. “I used to have dreams about my mother holding my hand and letting go. When she let go … [I] couldn’t stop falling until I awoke, drenched in fear and sorrow.”

Mary’s thinking evolves, but not in some magical moment of epiphany — rather, and more realistically, as a slow accumulation of facts that tip the scale. Having arrived at Nettleton as a teenager, she learns gradually how precarious it is to be a woman in a poisonously misogynistic culture.

It isn’t just Mary’s enthrallment to Vogel that “The Foundling” probes so well, but the way someone like Vogel can not only thrive under patriarchy but perpetuate it. The doctor comes to believe it is her destiny to rise above the limitations imposed on women, in part, through her presumed genetic and racial superiority. Vogel becomes not only a gatekeeper but a prison warden, keeping the “unfit” from besmirching the purity of an American social body weakened by World War I. For her, these views represent the height of science and reason, even though they depend on excluding any data that contradicts them.

“The Foundling” arrives in this century’s ‘20s, a time not so far removed as we’d like to think from the heyday of eugenics or its antiscientific methods. The opponents of everything from abortion to democracy put forth their own cherry-picked data to justify a world in which the natural order is always a pyramid, with them, by rights, on top.

Leary’s novel is ultimately a hopeful one, in which empathy and critical thinking reveal the structural vulnerabilities of such pyramids — built as they are on fabrications, compensations and contradictions that eventually undermine their foundations. Leary is optimistic that reason will prevail.

In ‘Matrix,’ the acclaimed novelist fleshes out the life of a mysterious medieval nun to build a glorious fantasy of female authority freed from men.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.