- Share via

On the Shelf

The Reformatory

By Tananarive Due

Gallery: 576 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

October is Black Speculative Fiction Month, but that doesn’t begin to explain why Tananarive Due is so busy. The author, screenwriter and professor who has been called the “doyenne of Black horror” is teaching “The Sunken Place” at UCLA — its title taken from a scene in Jordan Peele’s breakout film “Get Out.” Created in 2017, the wildly popular course explores racism and survival through the lens of Black horror film and fiction, drawing on her experience as the author of more than a dozen horror novels and executive producer of “Horror Noire,” a groundbreaking documentary on the subject.

And there is her writing. With the WGA strike settled, she and husband-writing partner Steven Barnes are working with producers to adapt two of her works for TV. (They wrapped work in the writers room on “Crystal Lake,” Bryan Fuller’s eagerly anticipated prequel to the “Friday the 13th” franchise, just before the strike). She’s supplemented her April short story collection, “The Wishing Pool,” with a new story for an anthology out this month, “Out There Screaming,” which was curated with an introduction by Peele. On top of that, she’s about to publish her second book of the year, “The Reformatory,” a coming-of-age novel about the horrors faced by Black and white children at an infamous Florida juvenile correctional facility.

An exhibition at REDCAT is built on Octavia E. Butler’s “Parable of the Sower.” Its creator, American Artist, talks with Tananarive Due.

Joe Monti, the new novel’s editor at Simon & Schuster, was surprised when the manuscript first came across his desk. He had spoken to Due about providing a blurb for Stephen Graham Jones’ “The Only Good Indians” but didn’t know she was working on a new novel, her first in almost a decade.

Monti had been on the lookout for BIPOC voices within horror for a few years. “Of course, I was aware of Tananarive as a towering presence in the horror community and had read ‘The Good House’ years before,” he said in an email. “But I came back to that book and read one of her earlier novels, ‘My Soul to Keep,’ to help define what I was looking for when I wanted to publish horror by looking at its recent past.”

While Due is a trailblazer in Black horror, she thinks often of other pioneers. As she speaks over Zoom from her home office in Upland about her three decades as a journalist and writer, a poster looms over her shoulder: the cover of “Freedom in the Family,” a 2003 memoir she wrote with her mother, Patricia Stephens Due, a civil rights activist who died in 2012. (Her father, John D. Due Jr., now 88, was a civil rights attorney.)

“I had the unwavering support of my parents, especially my mother,” Due says. “Even before I was published, my mother would buy me ‘The Writer’s Market’ [a guide to publishers and agents] every year as a birthday present. Writing mattered to my mother.”

But during her undergraduate studies at Northwestern University, Due received mixed messages about what kind of writing mattered. “While admiring Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ got me praise in my writing classes,” she remembers, leaning into the camera for emphasis, “liking Stephen King got me raised eyebrows.”

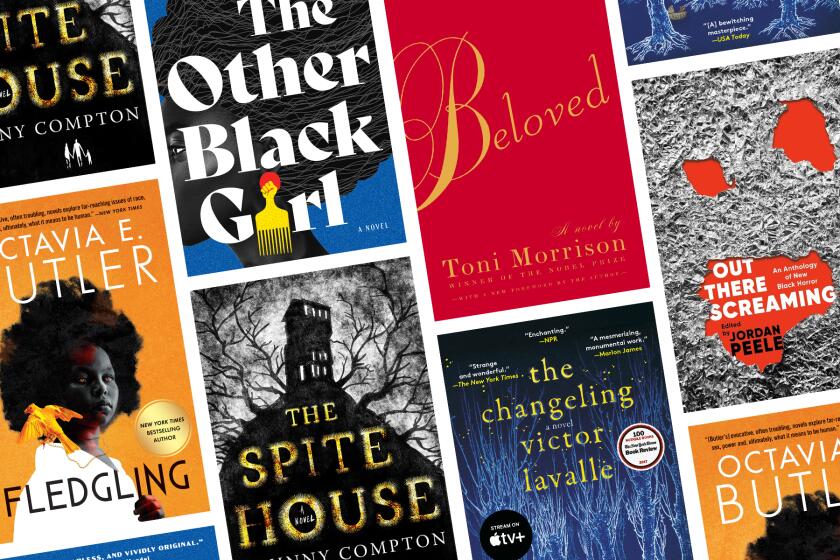

Black horror pioneer Tananarive Due helps us pick 6 great books from the genre, from a Toni Morrison classic to a new anthology by Jordan Peele.

Not so in the Due household. “My mother loved horror. That was how I learned to love the genre.” Due’s parents were self-effacing, but she gleaned from the history books that they were highly respected figures. Their genre approval should have been enough — and yet she wrestled with the weight of writing something meaningful. “I worried I would not be respected if I wrote horror,” she says. “I couldn’t give myself permission to even imagine myself doing that.”

A major turning point proved to be Due’s 1992 interview, as a reporter at the Miami Herald, with Anne Rice. Rice had been accused by critics of wasting her talent writing about vampires, but the bestselling author had the perfect comeback. “Rice said, ‘Everybody knows who Jane Eyre is … and everybody knows who Frankenstein’s monster is. These are great, powerful, heroic images that allow you to go outside of yourself to really talk about questions that change you.’” Rice went on to describe the impact of Homer on his listeners, transported by his epic tales of Achilles and Troy. “It was not just escape, but it was an escape that improves you. You go back feeling different. That’s what literature should do.”

For the record:

10:55 a.m. Oct. 26, 2023An earlier version of this article stated that Tananarive Due and husband-writing partner Steven Barnes are back in the writers room working on “Crystal Lake.” The two have wrapped work on the film. The article also stated that Due had won an NAACP Image Award. She was nominated for the award.

Nine months later, inspired by the notion that horror fiction could speak to life’s greatest challenges, Due finished “The Between,” a novel about a man whose belief that his near-death experiences have put him in a state of limbo almost destroys his marriage. Two years later, she followed with “My Soul to Keep,” the story of David Wolde, a 500-year-old African immortal who’s conflicted about his need to protect his identity, which would mean abandoning his human family. In 2009, “Blood Colony,” the third book in what had become the African Immortals series, was nominated for an NAACP Image Award.

Due was by then no stranger to accolades, but this nod marked another turning point. “My mother told me that, in the 1960s, the NAACP put a lot of thought and effort into establishing the Beverly Hills/Hollywood branch because they understood then the importance of representation, which was another front in the battle for civil rights.”

L.A.s 13 most essential works of speculative fiction, from Octavia Butler, Philip K. Dick, Aldous Huxley, Salvador Plascencia and many more.

Civil rights history was a constant in Due’s formative years. “My mother was such a griot in our family,” Due says. “That’s the reason I co-wrote ‘Freedom in the Family’ with her: not just to preserve the work of both my parents but, important to her, the work of other unsung activists whose stories would be lost save for her telling them.”

Due’s reverence for Black history — and the trauma it inflicted on everyday people who lived through its horrors — infuses “The Reformatory,” the suspenseful coming-of-age story of Robert “Robbie” Stephens, a 12-year old in fictional Gracetown, Fla., who’s sent to a notorious boys’ detention center for defending his sister from a white teen’s unwanted advances.

Inspired by the real-life loss of a relative in the 1930s at Florida’s infamous Dozier School for Boys, also the basis for Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Nickel Boys,” Due started the novel shortly after her mother’s death.

“We never had a chance to talk about what happened,” to the great-uncle who died at the Dozier School in 1937, Due says. Her sadness at the loss — and the missed opportunity — is palpable during our conversation. “There were so many times I wished I could change the history of the real-life Robert Stephens, dying so young in an unmarked grave at that horrible place. They said he was stabbed, but I believe there’s dishonesty in some of those records. And that’s not too far-fetched, because when you have complete control over an environment like that, you get to control the narrative.”

Due takes back the narrative by setting her novel some 13 years after her great-uncle’s death. The Reformatory is still a place where boys are brutally beaten for minor infractions while “haints” — ghosts of boys who died at the hands of the vicious warden — both guide and haunt Robbie. Much as this is a racism-as-horror story, however, “The Reformatory” is also about the heroism of Robbie’s older sister, Gloria, who embarks on a quest to free the brother who had defended her from sexual assault — and been brutally punished for it.

Jordan Peele knew “Get Out” had a shot. The reviews were glowing. The tracking was strong.

The speculative elements are sparse — a fact about “The Reformatory” that surprised Monti. “The horror is almost exclusively generated from its being rooted in Jim Crow-era Florida,” he says. “It’s the horror of Ellison’s ‘Invisible Man,’ and that’s why it’s so riveting.”

“The Reformatory,” along with several short stories in “The Wishing Pool” also set in Gracetown, weave together the many threads of Florida’s racial history and Due’s own family saga, creating a setting as potent as Stephen King’s Castle Rock is for horror fans. But Due’s inspiration for Gracetown is William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, albeit with one important difference: “I wanted my county to be a place where magical things happen, especially as they relate to Black children.” While there is definitely magic in Gracetown, it’s also a place where characters process and heal from trauma.

In the wake of “Get Out” and the “Horror Noire” documentary, Due started to make a connection between her mother’s love of horror and her trauma dating back to the 1960s. “My mother was tear-gassed by police and had to wear dark glasses because of damage to her eyes,” she recalls. “In another incident, her sister was kicked in the stomach. My aunt became so disillusioned with America that she immigrated to Ghana and broke out into hives every time she tried to come back to the United States.”

Due wonders whether horror was a balm for her mother. “There can be something strangely comforting about horror when you’ve actually been through trauma,” she says, “because on one level a book or a film is a validation of your emotions and fears. You realize you felt the same fear in a movie as in your real life, except it’s in a different context. And the more it’s a fantasy context, the more it can be separated from the actual trauma that you suffered. I have to believe my mother found it healing in that way. I don’t know if she would have agreed with that. But as I’ve gotten older and suffered my own traumas, the biggest being the loss of my mother, I get it now.”

In 2018, Jordan Peele became the first black writer to win an original screenplay Oscar.

Watching the aging and decline of her father, who now lives in Atlanta with her sister, has also made Due appreciate how horror can soothe. “I find comfort watching horror movies about caretaking because the real horror is watching someone you love who can no longer take care of themselves the way they used to,” she says. “The real horror is thinking about the loss of a loved one. But in a horror movie, that’s just where we start.”

Her eyes twinkle as she adds, “And then you add a demon, and the horror can get resolved.”

Woods’ “Inner City Blues,” the first in the Charlotte Justice series, was recently named by Time as one of the 100 Best Mystery/Thriller Books of All Time.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.