The many stages of Michael Mann, plus the best movies to see in L.A. this week

- Share via

Hello! I’m Mark Olsen. Welcome to another edition of your regular field guide to a world of Only Good Movies.

You are reading Indie Focus newsletter

Sign up to get Mark Olsen's guide to movies and what’s going on in the wild world of cinema in your inbox every Friday

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

To kick off the new year, the LAT movies staff came up with a list of 17 movies we are looking forward to in 2024. Among the titles included were Denis Villeneuve’s “Dune: Part Two,” Bong Joon Ho’s “Mickey 17,” Luca Guadagnino’s “Challengers,” George Miller’s “Furiosa: A Mad Max Story,” Steve McQueen’s “Blitz” and Marielle Heller’s “Nightbitch.”

I wrote about Ethan Coen’s “Drive-Away Dolls,” his first fiction feature directed without brother Joel, as well as Francis Ford Coppola’s ambitious, long-awaited “Megalopolis,” in which he invested large sums of his own money.

The men of Michael Mann

Michael Mann has already come up here a few times recently around the release of his new film “Ferrari,” still in theaters. The American Cinematheque is launching a tribute series this weekend, with Mann in person for a number of Q&As. The sharpness and vividness with which he recalls production details of his older films is riveting and will make for a great series of conversations. While the screenings are already sold out, there will be standby lines available.

The series will also bring into focus the ways in which Mann returns to certain archetypes throughout his work, but always brings something new, whether technically in his craft or in his ongoing examinations of masculine identity.

The series begins with a screening at the Egyptian of the 1995 film “Heat,” which has taken on a life of its own through fervent fandom. It will likely be the movie remembered as Mann’s singular masterwork. The performances by Robert De Niro and Al Pacino as, respectively, a thief and the cop out to catch him bring such intensity and power to the film. (“Heat” will also be playing in 35mm at the New Beverly Jan. 11-14.)

As Kenneth Turan wrote in his original review, “No one sees as much epic existential heroism in the romantic fatalism of hard men and the women who try to love them as Mann does.”

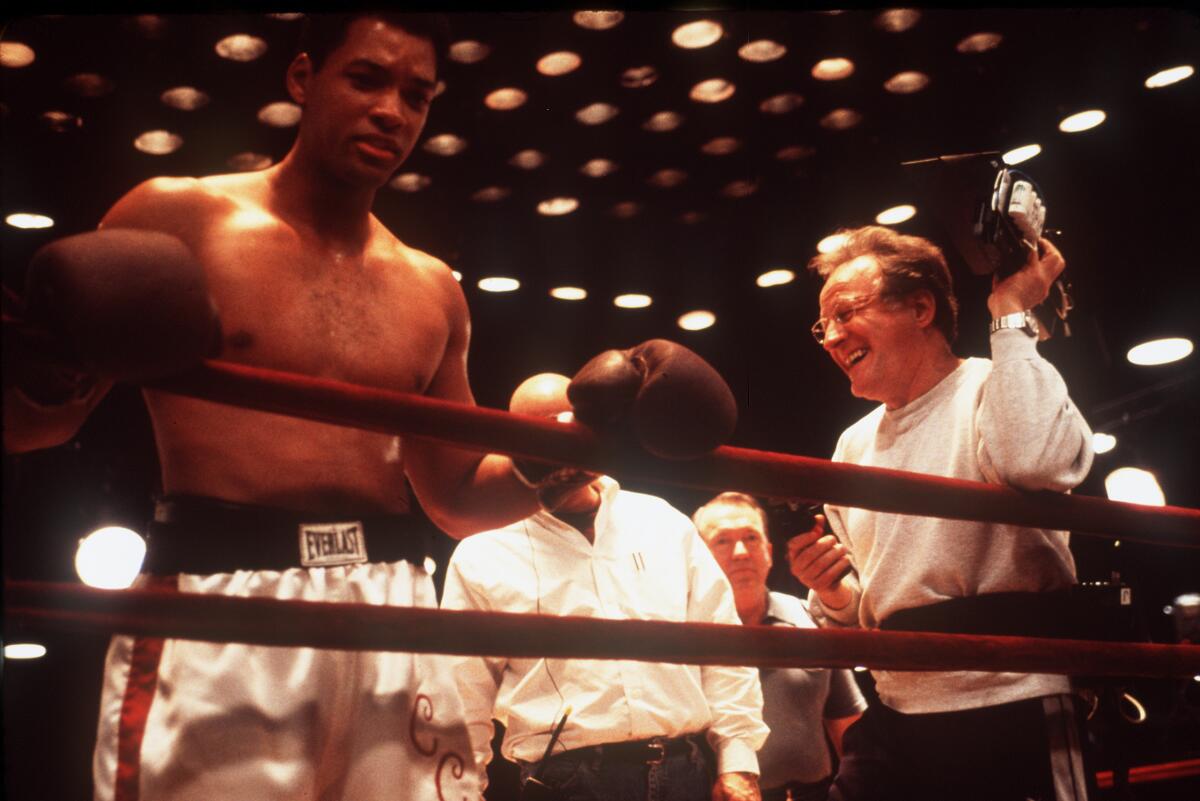

Saturday will see a double-bill at the Aero of “Ferrari” along with “Ali,” Mann’s 2001 portrait of boxer Muhammad Ali. (Of the films in the Cinematheque series, “Ali” screens the least often and may be the one really worth an extra effort to see.)

In a 2001 interview with Michael Sragow, Mann spoke about how he approached conveying the full sweep of what Ali had been through. “How did I come up with the structure?” the director asked? “Out of desperation, the way I come up with any of these things. I can’t possibly bring you into this movie with some expository scene. I have to bring people as much as I can into Ali’s life.”

The Tom Cruise-Jamie Foxx-starring “Collateral” will be playing at the Egyptian on Sunday, Jan. 14, with a Mann Q&A moderated by critic Katie Walsh, who co-hosts the “Miami Nice” podcast that exhaustively examines Mann’s 2006 movie version of “Miami Vice.”

In his review of “Collateral” Kenneth Turan wrote, “As a result of Mann’s craftsmanship and concern, ‘Collateral’ crackles with energy and purpose, a propulsive film with character on its mind and confident men and women on both sides of the camera. ‘It’s what I do for a living,’ Cruise’s Vincent likes to say when pressed. Making films like this is what Michael Mann does for his.”

Mann was also a part of our recent Envelope director’s roundtable, which is now available to stream on YouTube and broadcasting on Spectrum. As Mann said when asked to describe the job of directing, “It’s everything. You are the film, the film is you. You’re living every part of it, every component of it, and you’re trying to figure out what strategically, if I break down all the different tasks, what’s critical? What’s not critical? Everything’s expressive, but how is it expressive? So it’s kind of symphonic.”

A Colin Higgins double-bill

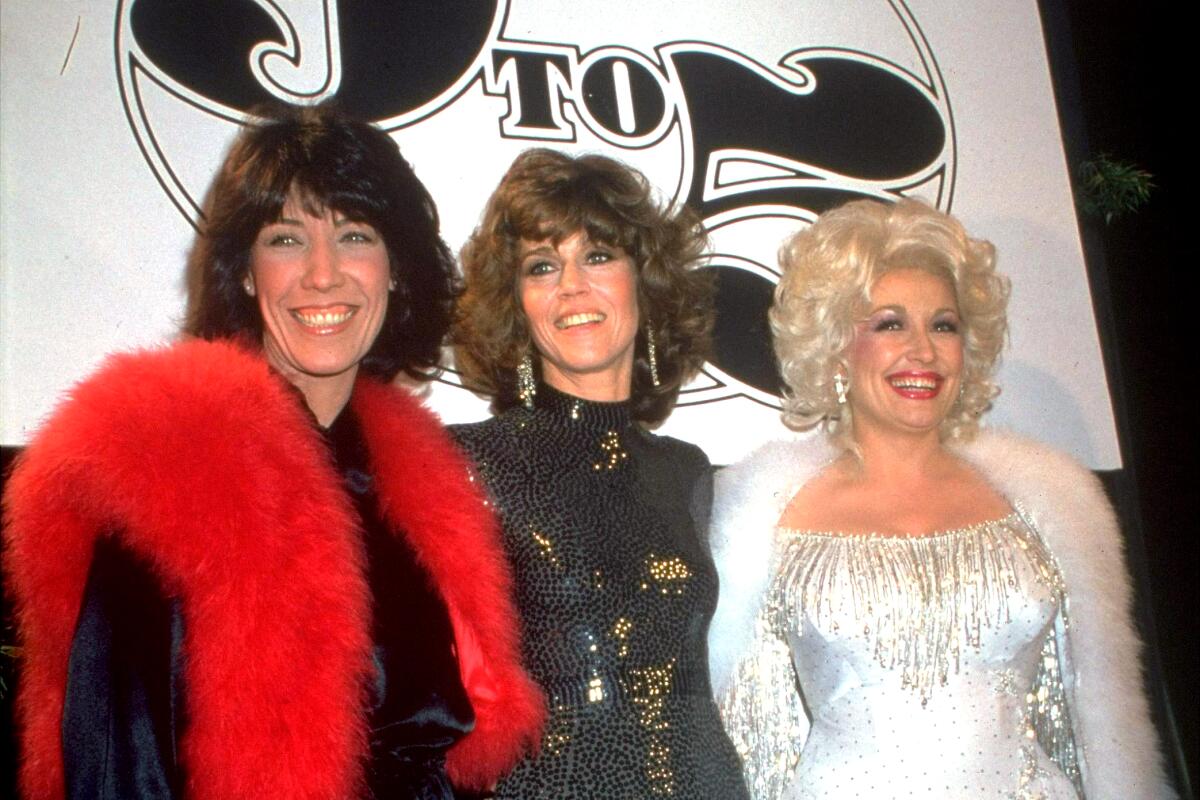

The New Beverly Cinema will be screening a double-bill of films directed by Colin Higgins on Tuesday and Wednesday, including 1980’s “9 to 5” and 1982’s “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.” Higgins is an intriguing and undersung figure, the screenwriter of “Harold and Maude” before transitioning into a directing career that was tragically cut short by his death from AIDS-related illness in 1988 at age 47.

“9 to 5” stars Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin and Dolly Parton (in her film debut) as three office workers who find themselves taking over from their chauvinist boss (Dabney Coleman) when circumstances lead them to accidentally serve him rat poison in his coffee and then kidnap him to cover it up.

In reviewing “9 to 5,” The Times’ Kevin Thomas wrote that the film’s stars “deliver the goods in high comic style, scoring some points for women’s equality in the office.” Thomas added that the film “appears to be an audience-pleaser that never missed an intended laugh. However, it strays so far from reality for so long that it threatens to become mired in overly complicated silliness and to lose sight of the serious satirical points it wants to make. Happily, it does pull together for a finish that’s as strong as it is funny. In short, its stars are more satisfying than their material, as good as it so often is.”

“The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” is an adaptation of the stage musical of the same name, in which a madame (Parton) and a friendly sheriff (Burt Reynolds) run afoul of a television personality (Dom DeLuise) and try to keep her brothel from being shut down.

In her original review of the comedy, Sheila Benson wrote that the star personas of Parton and Reynolds don’t mesh together well, “so we have two larger-than-life-size images that float through the movie like those vast Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloons. They can’t do much more than bump into each other regally and drift away.”

Benson did give special notice to Charles Durning’s song-and-dance number “Sidestep,” saying it “might very well be worth all the rest of the whole petty-vulgar movie put together and almost worth the price of admission. … This shouldn’t have been so much of a surprise. But it is — a real, tear-down-the-house show-stopper, the sort of number you play over and over in your head, savoring his deft, tiny foot movements and that vaudeville trick of putting his hat on sideways, then changing direction under it, so it’s on him the right way. The rest of the film should have such life.”

Other points of interest

‘El Norte’

As part of a series on films selected for the National Film Registry (itself established in 1988), the Academy Museum will screen Gregory Nava’s “El Norte” on Friday. Having premiered at the Telluride Film Festival in 1983, the film was released in 1984 and would go on to be nominated for an Academy Award for original screenplay. The story follows two siblings as they flee Guatemala and make the difficult journey to the United States.

Speaking to The Times’ Reed Johnson about the film’s 25th anniversary in 2009, Nava said, “We made the film not to make a commercial hit but to make a film about the human tragedy of a very tragic situation that still continues to this day. I’m very, very gratified that the film is still considered to be so relevant, and it saddens me because the issues are still there.”

De Palma and Schrader’s ‘Obsession’

Though it is now something of a lesser effort in both of their looming filmographies, the 1976 film “Obsession” brings together Paul Schrader as screenwriter with Brian De Palma as director. With a score by Bernard Herrmann to boot, the film is a self-conscious riff on Hitchcock’s “Vertigo”: An American businessman (Cliff Robertson) who has never fully recovered from the death of his wife and daughter 16 years earlier, falls for a woman (Genevieve Bujold) who reminds him of his late wife.

The film will be screening in 16mm at the Lumiere Music Hall on Thursday, Jan. 11.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.