Why everyone is talking about Bong Joon Ho’s ‘Parasite’: A thriller rooted in class conflict

- Share via

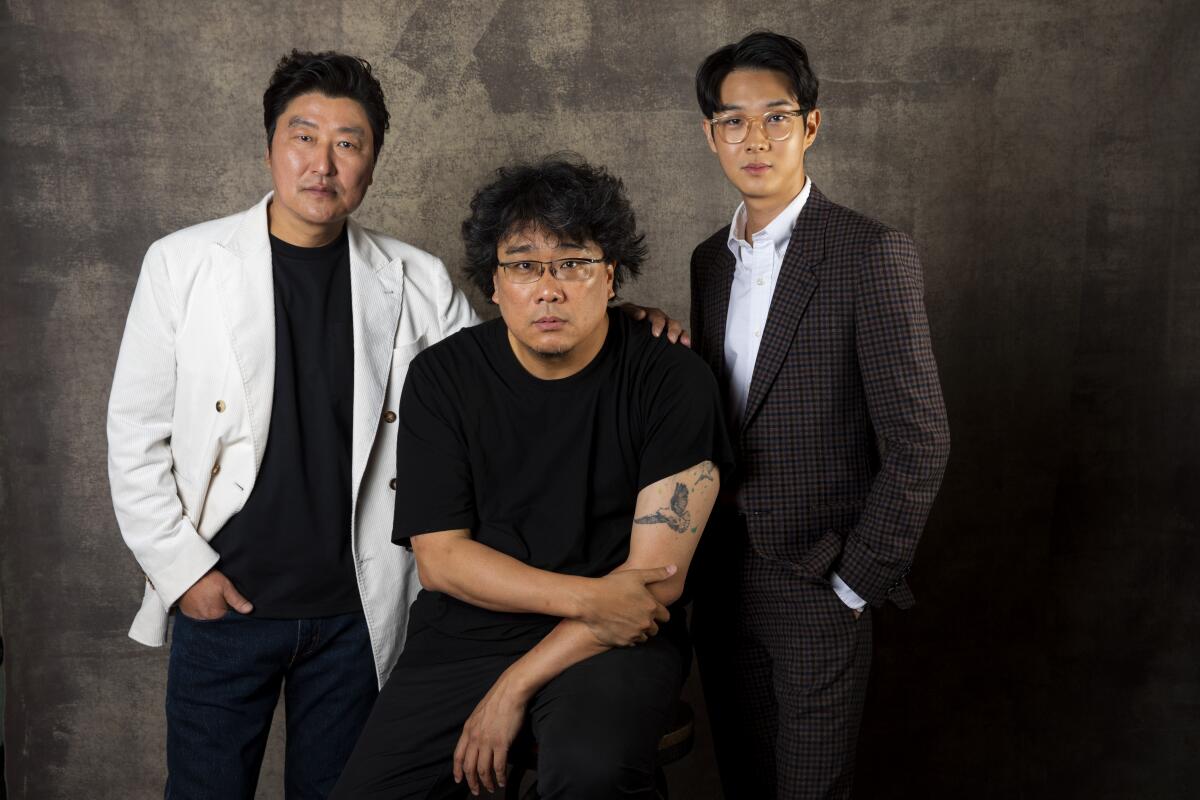

Filmmaker Bong Joon Ho was back in Los Angeles on a recent morning in September, on the dizzying stateside tour for his critically acclaimed thriller “Parasite,” when I asked if he’d heard the day’s news out of his native South Korea. He answered with an exclamation 16 years in the making.

“HE CONFESSED,” said director Bong, wide-eyed with astonishment.

Weeks earlier, Korean authorities had announced the identification of a suspect in the infamous serial killings that inspired Bong’s second film, “Memories of Murder,” the searing 2003 true crime drama he directed at the age of 34. The slayings had shocked and terrified the country three decades ago, the trail long gone cold.

On this morning in 2019, Korean media were reporting that the suspect had confessed. Bong, now 50, with seven feature films and the Cannes Film Festival’s Palme d’Or for “Parasite” under his belt, was floored by the news.

Two very different families collide in Bong Joon Ho’s masterful thriller, which will represent South Korea in this year’s Oscar race.

It had taken so long to glimpse the face of the monster he’d chased onscreen years ago in “Memories of Murder,” a film as much about a killer’s real reign of terror as the failure of justice to find him. The resolution was bittersweet, and Bong admitted he felt conflicted.

“But no matter how complicated I feel, I don’t think it can compare to the people who were actually involved in the case — families of the victims, detectives who struggled to catch the killer, and the suspects who were misunderstood to be the killer and were interrogated,” he said. They should be the ones to speak at length before he does, he added. “I feel very complicated, but I think it’s only a fraction of how much they feel.”

He recalled what he used to say while doing press for “Memories of Murder”: “To remember is to punish,” said Bong.

Resolution is not something Bong might expect to gain from any of the films he makes, but that doesn’t stop him from using them to exorcise the modern anxieties that plague him. Deliciously entertaining genre blenders, his stories tend toward cutting, witty and ultimately humane social critique, twisty puzzle boxes that reflect our world back to us.

His films expose the erosions of our collective humanity as a dwindling precious resource, from 2006 sci-fi breakout “The Host,” which pitted a working-class Korean family against an environmental monster, to 2013’s English-language “Snowpiercer,” the capitalist warfare-on-a-train actioner for which he enlisted Tilda Swinton and Chris Evans. 2017’s Netflix eco-thriller “Okja,” the tale of a girl and her super pig, excoriated the industrial farming complex enough to encourage some viewers to go vegetarian.

“Parasite,” his first fully Korean-made film since 2009’s mesmeric maternal-murder mystery “Mother,” follows a poor but enterprising clan who ingratiate themselves into the lives of a wealthy family with darkly comic and tragic results.

In his fourth film with director Bong, Song Kang Ho plays Ki-taek, the downtrodden patriarch of the Kim family. Neither he, his former shot put-champ wife, Chung-sook (Jang Hye Jin) or their grown children, Ki-woo (Choi Woo Shik) and Ki-jung (Park So Dam) can land a steady job; they share a cramped sub-basement apartment at the geographical and metaphorical rock-bottom of town. Their lives take a dramatic turn when Ki-woo gets a gig as a private tutor to the snobbishly rich Park family, proceeding to scam all the Kims into gainful employ in the moneyed household on a hill.

The concept took hold, as most of them do, over the span of many years in Bong’s mind. In his youth he’d worked as a private tutor to a rich middle schooler, and the memory of entering their upper-class home as an outsider stuck with him longer than the job did.

He started turning over the idea that would become “Parasite” while finishing postproduction on “Snowpiercer,” and that film’s overlapping themes bled into a more intimate, contemporary tale of class, greed and survival. Five years later, he took the finished script to Song.

“He always starts telling me the idea three or four years back, and it’s always very gradual,” Song explained. “He never lays out the whole project at once — he’ll only share bit by bit, over meals or over drinks. Even I get very curious as well. ... With ‘Parasite’ I was like, ‘What could this film end up being like?’”

Both men describe their relationship as one that never requires much talking or explanation.

“There are always these strange and uncomfortable moments across my films, and I think once those moments go through the filter and amplifier that is Song Kang Ho they become more realistic,” said Bong, speaking alternately in Korean and English with the help of a translator. “They feel more real as they reach the audience. I feel like they gain this persuasive power, through Song.

“Thankfully, Song has never hated the scripts that I write,” joked Bong, who co-wrote “Parasite” with Han Jin-won and is as quick to self-deprecating humor as he is game to philosophize. “We never fought over characters or certain scenes in the way we analyzed them — it’s always been very natural, like how the breeze flows through trees in a forest. It’s always been a natural flow.”

One of South Korea’s most respected actors, Song said director Bong knows his characters so well, he’d often act out scenes for his cast. “On set he would demonstrate for the actors — ‘This is how you should do it’ — and it’s so funny,” said Song. “The actors would try to imitate and follow what he does, but it’s impossible. That’s how good he is at expressing the characters.”

When we first meet for a coffee in the lobby of a swanky Toronto hotel, Bong has recently screened “Parasite” to resounding raves at the Telluride Film Festival, a mountain enclave of elite cinephilia. “But it was mostly industry people,” he said.

“Parasite” is already a blockbuster in South Korea, where it grossed $70.9 million this summer. He’s curious how North American moviegoers will receive it, with its universal class themes and culturally specific details — like the failed Taiwanese castella shop Ki-taek once ran, the frictions of modern South Korean socioeconomics, or the “ramdon,” a rendition of a jjapaguri instant noodle dish that centers one of the film’s most virtuosic suspense sequences.

The answer: Pretty auspiciously. Later that night, “Parasite” will play just as powerfully to viewers at the Toronto International Film Festival. After a quick trip back home to Seoul, Bong will return to the U.S. to see evidence of the film’s crossover potential as it plays, again to the rafters, with the genre-obsessed crowds at Austin’s Fantastic Fest and L.A.’s Beyond Fest, and then at the highbrow New York Film Festival.

Some viewers have shared that the film made them uncomfortable, “and I didn’t dislike that response,” said Bong. “I felt thankful for the audience members who felt uncomfortable but stayed to finish the film. I think it will be very meaningful to reflect on where that discomfort comes from — why do we feel uncomfortable?”

His films often feature working class-characters battling the systems in which they are trapped. Bong suggested that if his work demonstrates a social conscience it’s because he’s simply inspired by what he sees around him. “It’s not because I have some great obsession with politics, or want this to manifest in a political movement. It’s just something I go through and encounter every day.”

Even the most mundane of daily aspects, of individuals, all carry a political-social context with them.

— Bong Joon Ho

“Every time we pass by someone on the streets or the subway, regardless of whether or not we want to we can smell their scents,” he said. “And when we smell them we can kind of think about, ‘Oh, this person went through this today. This person is probably not doing so well today.’ We can all kind of feel that. I think even the most mundane of daily aspects, of individuals, all carry a political-social context with them.”

At Beyond Fest, Bong pointed to similarly minded recent films by Jordan Peele (“Us”) and Hirokazu Kore-eda (“Shoplifters”), to which “Parasite” has been compared: “I think it would actually be strange for an artist never to deal with this issue at one point in their career. ... It’s not as if we gather together as directors and talk about how we should make films about this issue,” he joked. “I think as artists it’s just an issue that we can’t avoid in this day and age.”

When“Parasite” won the coveted Palme d’Or in May, Bong became the first Korean filmmaker to be awarded that honor. Since then “Parasite” was selected as South Korea’s official 2020 Oscar submission in the newly dubbed international film category and has emerged as a strong contender for major nominations in multiple categories including best picture, screenplay and director.

His devoted cineaste fan following — dubbed the #BongHive during Cannes — have embraced the wave of “Parasite” acclaim and wear T-shirts emblazoned with “Bong d’Or,” a savvy marketing move by distributor Neon, which plans a gradual nationwide rollout for “Parasite” following the opening in New York and L.A.

But Bong is not one to bask in the attention or accolades. Asked about the “Bong d’Or” shirts, he lights up. His first thought, he said with a laugh, went to the other kind of bong, something he learned he shared a name with when he brought “The Host” to the U.S. in 2007. “B-O-N-G … [I thought] it would be great to have a gold bong. ‘Bong d’Or.’”

Times critic Justin Chang is filing dispatches from the 72nd Cannes Film Festival, which ran May 14-25 in France.

While attending prestige festivals like Cannes, Telluride and Toronto, the auteur — who co-founded his own film club at university and remembers learning some particularly spicy English while translating Spike Lee films into Korean off of illegal VHS tapes — has been excited to catch new work by filmmakers he admires. Once a film geek, always a film geek.

“For me personally, the more wonderful thing is those nine jury members, they decide everything,” he said in Toronto, reflecting on the Palme victory. “Everyone on the jury are fellow filmmakers that I really admire ... When [Cannes jury president Alejandro G.] Iñárritu said that the decision was unanimous … just that word really made me happy. It really freed me,” he added, smiling and pausing a beat. “And I felt very grateful because otherwise I would have been like, ‘Oh, who hated my film?’”

“‘Hollywood kid’ is a term we have in Korea for people who’ve grown up watching and being obsessed with Hollywood cinema,” said Song, who joined Bong in Toronto. “And director Bong is one of those people.”

Among the works that have lately invigorated Bong: Kelly Reichardt’s “First Cow” — “the most quiet and poetic film” — due out next year, and the Safdie brothers’ upcoming Adam Sandler vehicle “Uncut Gems,” which is “crazy,” he said, smiling. “It feels like an overdose of drugs. In a good way!”

Alice Rohrwacher’s “Happy as Lazzaro,” he says, was the last movie to make him cry.

He cries often in movies, actually, but not at your typical run-of-the-mill sentimentality. “For example, when I first saw Stanley Kubrick’s ‘The Shining’ — you know that iconic, very famous moment of slow-motion flood of blood from the elevators? It was so shocking and beautiful. I cried with ‘The Shining’ because I was like, ‘How was it even possible to shoot this?’”

Bong also shed tears watching post-apocalyptic combatants get sucked up into an epic sandstorm in George Miller’s “Mad Max: Fury Road.” “I was speechless and thought, ‘What a master.’” He paused, contemplating the savage perfection of Miller’s dystopia. “Such is a masterwork. Something we cannot describe with our words: All we can do is just cry.”

When we meet again in Los Angeles after Bong’s month of traveling, film festivals and nonstop press, he reveals that if he wasn’t a filmmaker he might have been ... a hermit. “‘Hikikomori.’ You know the word?” he asked, referring to the term, popularized in Japan, for a condition of extreme social withdrawal. “It was very likely for me to become someone like that.”

I think in a way, film saves me.

— Bong Joon Ho

“I think in a way, film saves me,” he said. “Because I’m a filmmaker I get to meet people and live a life. I think if I did not become a filmmaker I would just stay at home for 10 years at a time as a hermit. ... I have a lot of fears and anxieties. I always ask, how can I be less anxious?”

Of course, his next film ideas are already gestating — at least one inspired by something he read in the news and already alive, in his brain. One, he has teased, will be another Korean project that exists approximately in the horror realm. If he plays coy in interviews, it’s partly because he’s still putting the pieces together. “I have three parasites in my head,” he said with a smile. “They’re just squirming inside me.”

On this September morning, the day of the Hwaseong suspect’s confession, he contemplated his relationship with moviemaking and volunteered the far-off eventuality when he might, perhaps, even retire.

“It’s always a struggle,” said Bong. “It’s always a burden that I put on myself. And one day there will be a time when I have to stop, and I think I would feel horrible … but at the same time, free.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.