Looking back at SoCal’s first ska boom: Vespas, the O.N. Klub and Laurence Fishburne

- Share via

A case could be made that the ska music scene in Southern California was born in part because the longhaired dude behind the soundboard at the Whisky a Go Go on the Sunset Strip was playing too much classic rock.

“It was a brilliant club, don’t get me wrong, but if you went there to see the Specials or Elvis Costello, you’d have some hippie sound guy playing the Doobie Brothers on the sound system,” says Howard Paar, who in 1980 founded the O.N. Klub, an early ska, mod and ‘60s soul spot seven miles east on Sunset Boulevard in Silver Lake that burned brightly for four years. “It was so incongruous, especially in those wired, fast-paced days.”

The O.N. Klub and the vital West Coast ska-punk scene it helped spark are featured in a number of new books and podcasts that bring into the present a unique culture-clash L.A. moment. On Oct. 23, the Grammy Museum marked the convergence with an in-person panel that focused on the roots of Southern California ska.

The conversation featured nearly a dozen insiders, fans and scholars, including Paar, whose new book “Top Rankin’” is a self-described “punk/ska noir novel” that uses as its backdrop the O.N. Klub and the scene it birthed. Writer and musician Marc Wasserman’s new book and accompanying podcast, “Ska Boom! An American Ska & Reggae Oral History,” features chapters on Los Angeles and Orange County ska. The event was emceed by DJ and reggae scholar Junor Francis, co-host of the “History of L.A. Ska” podcast.

Members of local ska-driven bands Fishbone, the Untouchables and the Boxboys offered recollections on their work and actor Laurence Fishburne recounted his early years in L.A. as a self-described “skankster.”

“I had a big radio and I looked like I came out of Brixton in London. I would play the Specials and walk up and down Hollywood Boulevard,” Fishburne told the crowd.

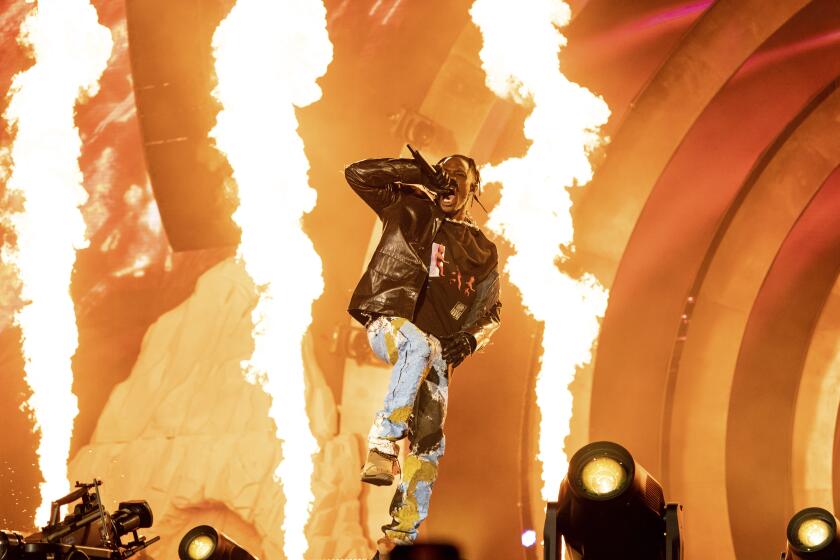

Music festival goers recount the chaos of that day, when eight people died, two dozen were hospitalized and scores more were injured.

As central to Southern California as Dodger dogs and skateboarding, ska, the early-’60s, Jamaican-born upbeat precursor to reggae, has experienced revivals nearly every decade since the early 1980s, but here — and across the Golden State — it’s never really gone away. More than 50,000 fans follow the Alameda-based Ska Punk Daily page on Facebook, and the Long Beach-based record label International City Recordings recently issued “4th Wave Ska,” a compilation gathering 25 bands from around the world.

The original SoCal ska wave was triggered by the British ska craze of the late 1970s, when artists on 2 Tone Records, including the Specials, Madness, the English Beat and the Selector skanked their way and onto the charts by injecting punk energy into the music first played by the Skatalites, Prince Buster and the Wailers. L.A. outfits including the Boxboys, the Untouchables and Fishbone amped up that uniquely Jamaican rhythm with teen-driven energy.

Unlike the mostly white punk scene, ska was an integrated movement, a trait that remains a crucial distinction. In Southern California, that sense of purpose helped spawn the ska-informed bands that stormed the charts in the 1990s, including No Doubt, Save Ferris and Sublime.

Paar, who in the subsequent decades has become a successful music executive and music supervisor, was a young British expat living in Los Angeles. He’d secured the keys to a former Vietnamese restaurant, Oriental Nights, near the intersection of Silver Lake and Sunset boulevards after its owner discussed opening a punk club. “I went into an impassioned rant,” Paar recalls. “It was the dawn of hardcore and punk was getting very head-bangy and misogynistic. Kids who were into high school football were suddenly in the mosh pit.”

Paar’s pitch: Unlike crowded punk club lineups, the O.N. Klub would “only do one band a night — ska, soul or reggae — and then I’d DJ the rest of the night and play records that matched it.” Through a combination of what Paar calls “passion and desperation,” the owner signed on. Among the most popular acts were the Boxboys, widely considered to be the first Southern California ska group, and the Untouchables, the first L.A. ska band to sign to a label, Stiff Records.

Said the Untouchables’ Jerry Miller during the panel: “Through word-of-mouth, people from around L.A. County and Orange County converged on the O.N. Klub. I was like, ‘Where did all these people come from?’ I thought we were the only ones doing it, and lo and behold, we weren’t.”

The Untouchables, a band founded by Miller, Chuck Askerneese, the late Clyde Grimes and others, earned their most prominent attention when they appeared with their Vespas in a scene from the 1984 sci-fi comedy “Repo Man,” where they prevent, with a few swift kicks to the stomach, Emilio Estevez’s character from repossessing a relative’s station wagon. The band’s most popular songs, “I Spy for the F.B.I.” and “What’s Gone Wrong,” were regional hits but failed to crack the charts.

Though Boston, Chicago and New York had their own variations in the ‘80s, writer Wasserman says that in L.A., “you have a bringing together of not only the music but the style in a way that doesn’t happen in a lot of other ska cities. There’s great weather so you can get a scooter, ride it around and look cool.”

Fishburne described the Silver Lake ska scene as being “straight out of ‘Quadrophenia,’” referencing the cult-classic 1979 film — based on the Who’s 1973 rock opera of the same name — about turf wars between mods and rockers in working class Brighton, England. The movie highlighted the scooter culture that propelled the mods, and Southern California youth took to the distinctive form of transportation. As with lowrider culture, the Vespa-obsessed tricked out their scooters with stylish accents. One local L.A. news segment from the early 1980s noted that scooter sales in Orange County had jumped by more than 20% due to “the mod scene.”

The movement coopted “Quadrophenia” fashion as well. The stylistic prerequisites included army-surplus trench coats festooned with pins and badges, pork pie hats and anything with a checkerboard pattern. Unlike sloppy punks, the crowd preferred short, clean haircuts and tight-fitting suits.

Talking on a podcast about his support of Marilyn Manson and DaBaby, the rapper now known simply as Ye said he’s ‘above’ cancel culture.

The style driving the city’s ska and mod movement was notable enough at the time to earn a feature in The Times’ fashion section. “Mods: Stylish Code Makes a Movement” described its members as being “a new breed of well-behaved young people whose trademarks are shiny Vespa scooters.” One attendee of the O.N. Klub, asked whether the scene was more than just a passing fad, replied with certainty.

“I know I’ll still be into it when I’m older,” replied the teen. “I’m just starting to get lots of lights on my scooter.”

Along the way, the O.N. Klub drew its share of marquee names. Parr recalls the night that Tom Waits and Rickie Lee Jones paid their cover charge, started walking in “and pulled the ratty curtain back. [Jones] looked at the insanity on the dance floor and did a knife-throat-slash and they got into a huge argument about it. She left, he stayed.” Paar added that members of bands including Blondie, the English Beat and the Clash came down after their Palladium shows to hang out. Years later, Jodie Foster told Paar that she used to go dancing there.

“It was fun. It was loose,” said Paar.

By 1984, Paar had met so many music professionals that his own opportunities were expanding. After booking a few other clubs, he shifted to publicity in the 1980s. Paar has since become an award-winning music supervisor, earning acclaim for his work for films and series including “20th Century Women,” “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” and “The L Word.”

As he did so, the sound he helped foment at the O.N. Klub grew to become a multimillion-dollar business, spawning festivals, clothing lines and record labels. And though third-wave ska’s reign in the late 1990s had subsided within a few years, a backyard concert scene in Orange County and the San Fernando Valley continued virtually unabated until the COVID-1`9 pandemic, one fueled by renewed interest in Berkeley ska-punk legends Operation Ivy and Rancid.

“A lot of that is driven by Mexican and Central American kids,” says Wasserman, adding that “Mexico itself is one of the leading countries for ska in the world.

“The beauty of ska is it’s always been rebellious music,” he adds. “And it’s still appealing to these kids, who have heard it from their parents or even their grandparents at this point.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.