Newsletter: Essential Arts: What Europe’s Gothic architecture took from Islamic design

- Share via

I’ve been studying up on the first episode of “Keeping Up With the Kardashians” because it’s important to know our culture’s origin stories. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and urban design columnist for the Los Angeles Times, and now that I’ve delivered that critical Kardashians update (with many thanks to my colleague Yvonne Villarreal) it’s time to move on to the artsy fartsies:

The Islamic influence

It began with a tweet.

On April 16, 2019, a day after the Notre Dame Cathedral had been engulfed by flames in Paris, Middle East scholar Diana Darke noted on Twitter that the great icon of French nationhood was in fact inspired by Syrian architecture. “Notre-Dame’s architectural design, like all Gothic cathedrals in Europe, comes directly from #Syria’s Qalb Lozeh 5th century church,” she wrote. “Crusaders brought the ‘twin tower flanking the rose window’ concept back to Europe in the 12th century.”

She followed the tweet up with a blog post titled “The heritage of Notre Dame — less European than people think.” The article went more in depth on Qalb Lozeh (which means “Heart of the Almond” in Arabic). She also noted that some of the design elements prevalent in Gothic architecture can trace their origins to the buildings of the Umayyad dynasty, a Damascus-based caliphate whose descendants later ruled Moorish Spain. (Known as the first great Muslim dynasty, their rule began in the 7th century.)

Darke has expanded that fascinating post (which garnered international media attention) into an equally fascinating book, “Stealing From the Saracens: How Islamic Architecture Shaped Europe,” which was released by Oxford University Press in the United States last November.

And it is revelatory.

In it, she charts the influence of structures such as the 7th century Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, also known as the Dome of the Rock (and recently the site of crackdowns against Palestinian protesters by the Israeli military). Some European crusaders mistook Al Aqsa as the biblical Temple of Solomon, looking to it for inspiration in their own religious architecture.

Among the influences derived from Islamic design was the pointed arch. While not specifically a Muslim innovation (isolated examples existed in locations around Persia and Syria prior to the advent of Islam), its use was spread far and wide via Muslim religious shrines such as Al Aqsa. There are practical reasons for its spread, too. A pointed arch is stronger than the rounded Roman arch, therefore allowing for the construction of taller buildings.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

These innovations came partly from advancements in mathematics during the Islamic Golden Age (which ran from about the 8th to the 13th century). As Darke writes, it was a scholar of Turkic origin, Al-Khwarizmi (c. 780-846), “whose name was Latinised as Algoritmi, from which we get the Western word ‘algorithm.’”

The book details countless other points of influence that emerged out of Middle Eastern and Islamic architecture and centuries later became design staples in Europe. Among them: the rose window, the trefoil arch, as well as sophisticated dome construction and stained glass fabrication techniques — not to mention the minaret, which was likely repurposed as a bell tower by Christians.

Darke tracks how some of these influences were absorbed into European design — via returning Crusaders, roving guilds of masons, Islamic rule in Spain and through cosmopolitan sites of trade such as Venice, where lacy constructions bear the imprint of Middle Eastern influence.

In one particularly startling juxtaposition, she shows the architectural similarities between London’s iconic Big Ben and the minaret from the Great Mosque of Aleppo in Syria (an Umayyad building). Both are squared off towers that rise in four sections, and both are decorated with similar elements, such as trefoil arches. (The minaret, sadly, collapsed during clashes in Syria’s civil war in 2013).

A particularly exciting episode (Hollywood, please take note) details the treacherous odyssey made by the 20-year-old Abd Al-Rahman, grandson of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham, to Spain in the 8th century. It was a cinematic escape from political opponents that led to the establishment of eight centuries of Islamic rule in Spain.

Though dense in parts, “Stealing From the Saracens” ultimately reveals the countless ways in which Western culture has been shaped by Islamic thought — including here in the United States. (Gothic architecture has inspired plenty of religious and academic architecture all over the U.S. Just look at all the pale facsimiles of the style currently planted all over campus at USC.)

And in that regard, Darke’s book serves a vital purpose. “Are we ready, in the current climate of Islamophobia,” she writes in the introduction, “to acknowledge that a style so closely identified with European Christian identity owes its origins to Islamic architecture?”

Darke is unsure of the answer to question. But her eye-opening book is a solid first step.

Design time

For the price of a McMansion in Brentwood, writes classical music critic Mark Swed, Inglewood got itself a new concert hall. Well, not entirely new. The Beckmen YOLA Center occupies what was once a dilapidated bank building on South La Brea Avenue, which has now been reconfigured by Frank Gehry and his team into a new practice and performance space for the LA Phil’s Youth Orchestra Los Angeles. The hall isn’t open yet. But Swed got in for an early sound check.

In other Gehry-related news: Philly Inquirer architecture critic Inga Saffron has a look at his firm’s redo of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a renovation project that has been 15 years in the making. It’s a design that defers to the building’s original design, executed in the 1920s by a collaborative team that included Horace Trumbauer, Julian Abele, Paul Cret, C. Clark Zantzinger and Charles Borie Jr. “Instead of wreaking havoc,” writes Saffron, “the 92-year-old architectural radical has played against type and given museum officials precisely what they wanted: clarity, light, and space.”

And the Venice Architecture Biennale has opened its doors in Italy. The show was already in the works when the pandemic hit, but it nonetheless was set to address global issues such as climate change, mass migration and inequity. “The pandemic will hopefully go away,” curator Hashim Sarkis told the New York Times. “But unless we address these causes, we will not be able to move forward.”

Plays and players

Culture reporter Ashley Lee talked with filmmaker Jon M. Chu about the making of the cinematic version of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway musical “In the Heights” and the ways in which he was inspired, early on in his career, by movie musicals. “There’s a truthfulness of why music and dance exist in these stories in the first place,” Chu tells Lee. “It’s not because a melody is catchy but because just saying the words isn’t sufficient to communicate whatever that character wants to express.”

Jessica Gelt writes about the Geffen Playhouse‘s new virtual musical for kids, “The Door You Never Saw Before.” The show, whose themes explore the isolation of the pandemic, literally brought her to tears. “Along the way, children choose which door to open or not open, and whether to visit the overpass or underpass, the lost and found or the library,” she writes. The actors play “a variety of characters whose songs gently tap into deep emotions children may have dealt with during an isolating year.”

In the galleries

As the USC Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena reopens, it will be with a new lens on the collections, reports Times contributor Scarlet Cheng. This includes a reevaluation of the nature of the objects (such as those that exoticize Asian cultures), as well as their provenance. Plus, the museum is looking to integrate more contemporary artists into the program. “The Asian experience and the Asian American experience is so flattened by the way we typically talk about it,” says curator Rebecca Hall. “As a curator, I know artists can fill that out in a rich way.”

The L.A. landscape

A frequent trope about Los Angeles is that it is not a philanthropic city (one repeated in a recent story in the New York Times). Well, I looked into the numbers and found that the assertion simply isn’t grounded in fact. Not only does L.A. score above average on giving, it is several notches ahead of New York. But, ultimately, megadonor philanthropy is not something a city’s art scene should rest on. As I argue this week, it’s time to “retire the outmoded idea that the most important factor in a city’s cultural landscape is the presence of some white knight bearing a checkbook.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Which reminds me, D.J. Waldie published this excellent assessment of Eli Broad‘s legacy early last month: “Often the buildings he fretted over reflect Broad’s image more than the city’s, particularly the cheerless museum he named for himself.”

This week, the L.A. City Council voted to approve historic-cultural monument status for the building that once harbored the studio of Corita Kent, who made a name for herself in the 1960s as the “Pop Art Nun,” producing work that pushed the boundaries of convention. I write about why the designation is a big deal: It’s a rare case of a solo female visual artist being honored in the city’s landscape.

Plus, the Huntington Library has acquired a cache of images that depict daily life in L.A.’s old Chinatown.

Sort of related: the National Trust for Historic Preservation has issued its yearly list of the 11 most endangered historic places. Among them, the Trujillo Adobe in Riverside and Summit Tunnels 6 and 7 and the Summit Camp Site in Truckee, important Transcontinental Railroad links built by Chinese railroad labor.

Art after coronavirus

The Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra on June 26 will be the first group to take the stage at Walt Disney Concert Hall since it was shuttered by the pandemic more than a year ago. Among the invited guests will be 200 winners of a ticket giveaway (for those who are fully vaccinated). Plus, there will be plenty of rules governing everything from staging to audience seating. “It’s been an exercise in organizational agility and fluidity,” Executive Director Ben Cadwallader tells The Times’ Deborah Vankin.

The Music Center has also returned from its somnolent state with its outdoor Dance at Dusk shows. Jessica Gelt attended a tap extravaganza featuring a performance by queen of tap Dormeshia. The show, she writes, awakened “L.A.’s cultural nerve center.”

A survey sponsored by the American Alliance of Museums shows that damage from the pandemic may not be as severe as originally anticipated. Last year, it was reported that nearly a third of U.S. museums might permanently shut down as a result of COVID-19. That number has now been revised to 15%.

Essential happenings

As LGBTQ Pride Month kicks off, The Times’ Matt Cooper rounds up the best things to do, including an outdoor exhibit organized by the ONE Archives Foundation and a virtual benefit featuring performances by Lil Nas X, Dolly Parton and Ricky Martin.

The Natural History Museum has created a worthwhile online exhibition component for Barbara Carrasco‘s portable mural, “L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective,” which it recently acquired. This includes the ability to zoom in on key details and read background on the histories and historical objects that shaped the work.

If you’re looking to see something IRL, make time for “When I Remember I See Red: American Indian Art and Activism in California” at the Autry Museum of the American West. This group exhibition captures a period in which increased Indigenous activism over issues related to civil rights and federal termination policies (which sought to put an end tribal autonomy) brought together Indigenous communities from around the country in potent ways.

The show includes some stunning paintings by Tony Abeyta, Dalbert Castro, Frank LaPena and Rick Bartow, as well as a set of wry sculptures by Mooshka (born Kevin Cata) that riff on kink and kachinas. Also in the show: the logbook employed during the Indigenous occupation of Alcatraz in the 1960s and ‘70s, described by one scholar as that protest’s “holy grail.” (I wrote about it late last year.)

“When I Remember I See Red” is on view at the Autry through Nov. 14, autry.org.

Passages

Raimund Hoghe, a German dancer and choreographer who served as a dramaturge to Pina Bausch and later incorporated his physical disabilities into his work, has died at 72.

Chi Modu, a photographer who helped chronicle rap’s ascendancy, making portraits of figures such as Eazy-E, Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G., is dead at 54.

Sophie Rivera, a photographer known for her elegant portraits of Puerto Rican New Yorkers and other inhabitants of the city, is dead at 82.

Jay Belloli, an independent Los Angeles curator who was intrigued by the ways in which art intersected with space (the galactic kind), and who served as interim director of the Pasadena Museum of California Art from 2016 to 2017, has died at 76.

In other news

— A report that is equal parts chilling and enlightening on how robots are being used to mitigate isolation among the elderly.

— How a group of dancers confronted state violence in Colombia with some well-timed vogueing. A remarkable piece about dance as resistance.

— Urban design often overlooks the needs of teenage girls, writes critic Alexandra Lange. A new movement is trying to change that.

— Some execs at L.A. Metro want to keep widening freeways, despite what the residents around those freeways or the EPA have to say about it.

— The Mexican government sent troops to seize land next to the ruins of Teotihuacán, where authorities have reported that bulldozers were wrecking part of the outlying parts of the ancient city.

— Good recycling: A New York City art project repurposed plywood that was used to shutter storefronts during last year’s protests.

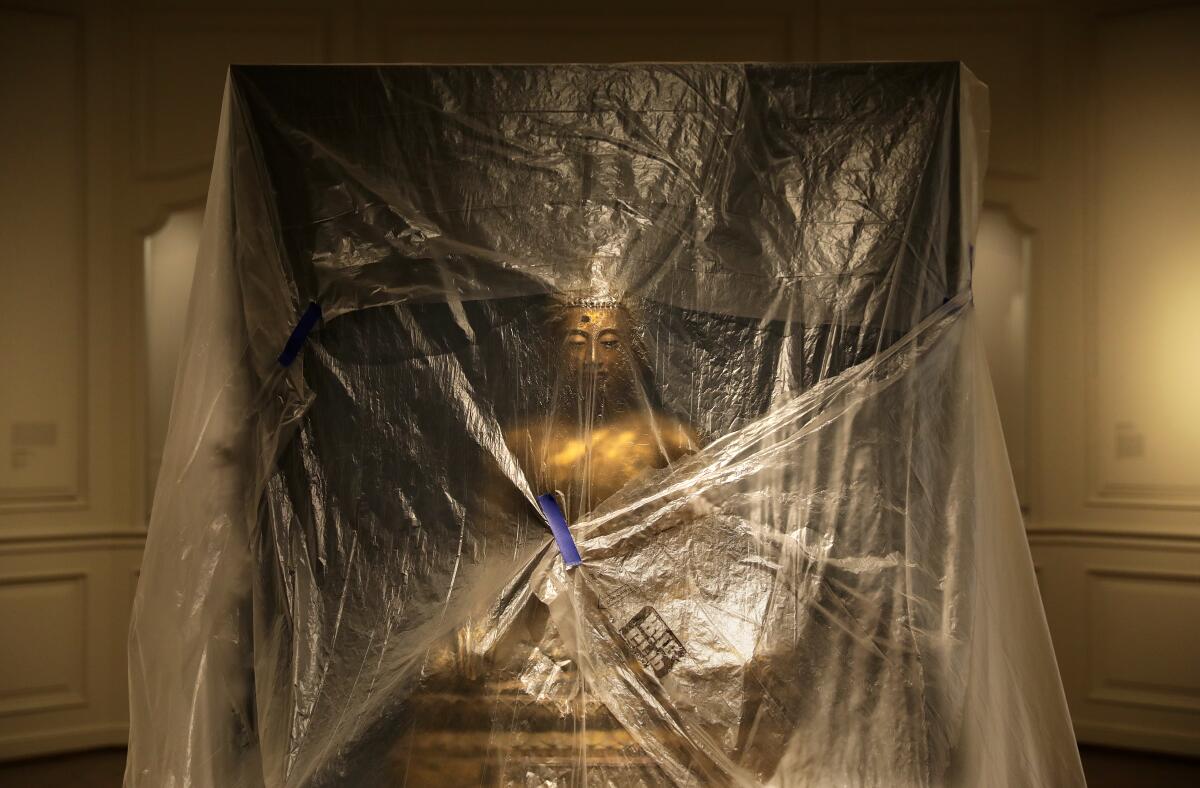

— “The Hiroshima Panels,” a series of famous paintings made by Iri and Toshi Maruki in reaction to the atomic bombing of Japan, are set to receive needed conservation work for the very first time. (Contributor Jeff Spurrier wrote about these singular works for The Times last summer.)

— John Yau digs into the mysteries of Jasper Johns’ “Green Angel” motif.

— Jillian Steinhauer on the art world’s fetish of “rediscovering” old women artists.

— In Wisconsin, Mary Louise Schumacher reports on Art Preserve, a unique exhibition site that marries an art museum with an art storage facility for unique works by folk and self-taught artists. Highly intriguing!

— Emily Colucci is not having the wall text for the Alice Neel show at the Met.

And last but not least ...

I’ve really been enjoying the poetry of “Lost Notes,” culture critic Hanif Abdurraqib’s music history podcast for KCRW.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.