Why these photos of California’s coast are not what they seem

- Share via

Is “criming” a word? The dictionary folks at Merriam-Webster have had criming on their “words we’re watching” list for a while now, noting that “the word ‘crime’ has mostly stuck to being a noun for its half-millennium existence, [but] we’ve recently seen the word reaching into new verb territory, especially in its present participle form.”

Criming is all over social media these days, where we’re watching a functional shift in grammar unfold. The riveting televised Jan. 6 select committee hearings are no doubt the current accelerator — and judging from the past few days, it’s looking like we are about to hit peak criming. I’m Times critic Christopher Knight, in for Carolina A. Miranda this week, and here’s the latest essential arts news:

Seductive estrangement

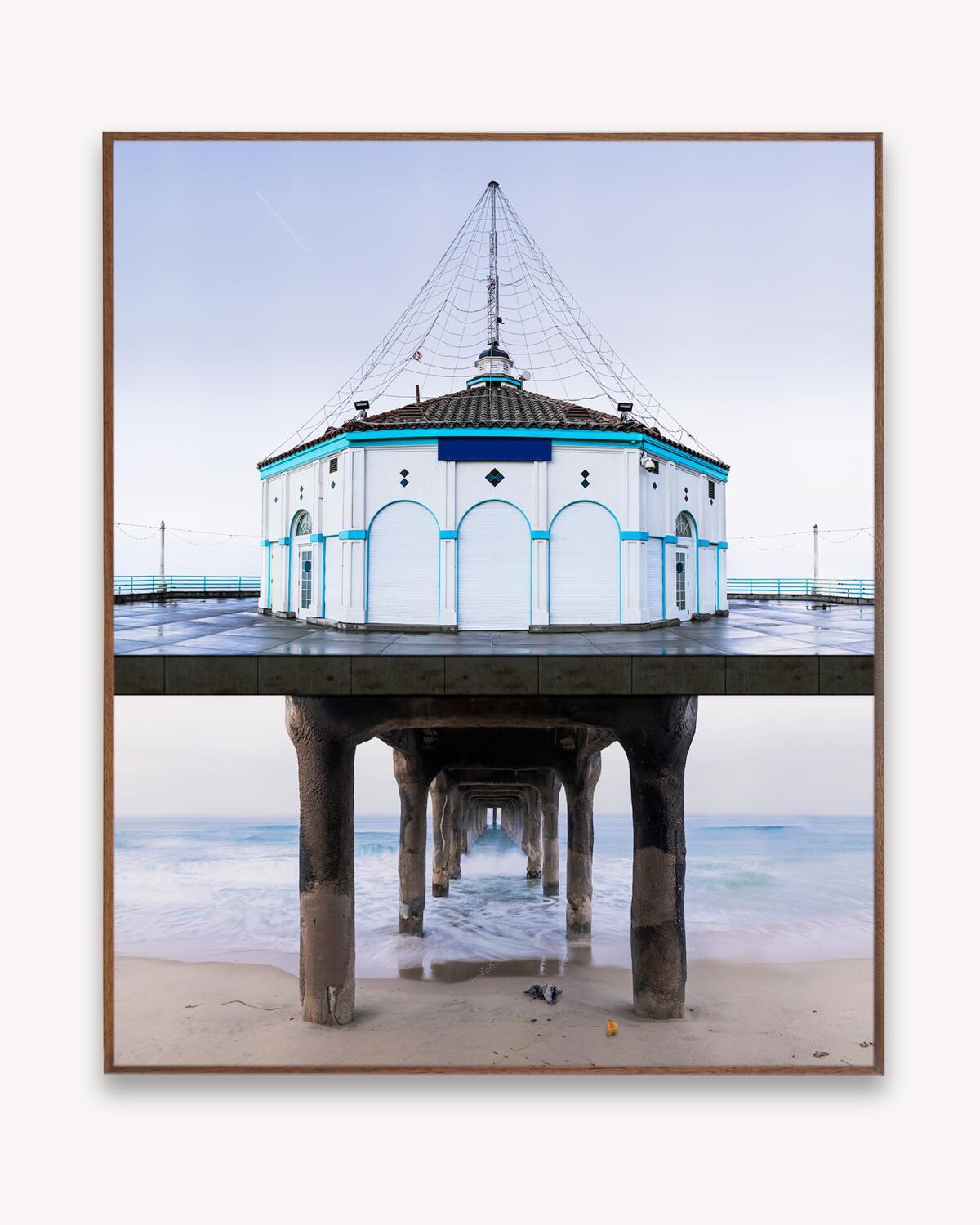

Pandemic disorientation is a surprising subtext of seductive new landscape photographs by Amir Zaki. Twenty-two color photographs at Diane Rosenstein Gallery, all made in 2021 as urban lockdowns and domestic quarantines were underway, show shoreline piers along the California coast. Although the occasional seabird does show up, the piers are unpopulated by human activity. Unpopulated, that is, except for the deft hand of the artist, who creates a subtle sense of estrangement.

They take a visual cue from the celebrated minimalist taxonomy of the late German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, who systematically recorded water towers, blast furnaces, grain elevators and other industrial structures, or the California bungalows and dingbat apartments photographed by Judy Fiskin. It takes a bit of looking to realize that the large-scale, frontally composed pictures, most 2 feet wide and 2.5 feet high, aren’t what they at first appear to be.

Each colorful landscape image is cut in half by a wide band that goes edge to edge — what appears to be the blunt end of the pier. Top and bottom seem to go together, mostly because we casually assume that a camera’s lens captures a transparent view of an actual scene. Here, however, something appears to be quietly out of whack.

Each pier is the site of a restaurant, a sport fisherman’s outpost, a Red Cross station, a tourist lookout or some other mundane use, all of them shuttered and closed down. The top perspective is just above eye level, so that the raised platform’s function is on clear view. Below, where massive wood or concrete structural pilings hold up the pier, a scene of roiling Pacific seawater, lazy waves or wet sand spreads out.

Slowly it dawns that there is no way for a person to get from the ground up onto the pier — no stairs, no ladder, no gentle rise where the platform might meet a bluff. Sorry, you can’t get there from here. Zaki’s seamless compositions digitally stitch together separate photographic imagery. The horizontal band, repeated in all the photographs, is a patch. For all a viewer knows, the pier and the supporting posts may or may not even be from the same location, such is the otherwise convincing fiction of the scene.

A pier is a meeting ground between two distinct realms — sea and land. As the catastrophic viral pandemic of COVID-19 was raging around the globe last year, killing more than 6.3 million people (so far), Zaki was out photographing at the plane of transition where, a few hundred million years ago, life crawled out from the sea. The L.A. artist’s pictures record the site of the arrival of an evolutionary process whose lineage created us — a place that has left us cut off today.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Zaki titled each photograph with the year a pier was built, dutifully followed by notations of the years in which the structure was seriously damaged or had to be rebuilt, given the force of nature’s destructive power. The oldest California pier was constructed in 1872 (in Ventura) and, according to the title, was damaged in 1878, 1887, 1921, 1973, 1983, 1986 and 1987, with renovations in 1928 and 1930.

All is not lost, however, as a bit of curdled hope peeks over the horizon. The piers in the pictures being fabrications, what you see is not documentary. Zaki’s shrewd and elegant digital photographs offer the newest pier renovation, so life does go on — at least for the moment. Whether that digital sleight-of-hand ranks as construction, damage or perhaps both is up to you.

Tuesdays-Saturdays, through July 16, at Diane Rosenstein Gallery, 831 N. Highland Ave., L.A. (323) 462-2790.

Outrage of the week

Cal State Long Beach’s art museum has decided to use its walls to showcase the painting of (surprise!) a major donor. Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld gave $10 million to the institution formerly known as University Art Museum, and now Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld artwork is exhibited inside the Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Gallery at the renamed Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum.

“A permanent chunk of a public university’s tax-subsidized museum facility and artistic program has been effectively privatized to advance the personal interests of a wealthy patron,” I write in a column. “CSULB has now made a sizable commitment to continuing in perpetuity a worthless but high-profile art project.

“What is the university teaching students through such an arrangement?”

Now I’ll turn over the newsletter to my Times arts colleagues, who will run down the rest of the week’s culture news.

Design time

Architecture critic Alexandra Lange’s latest book, “Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall,” is well timed for a city whose most famous mall magnate is running for mayor. Carolina A. Miranda dials into Lange’s arguments, including observations that plentiful seating and generous air conditioning make malls great places for seniors to socialize. “Commercial imperatives accidentally created an architecture that accommodates those who often have the least societal power: the young, the old, the disabled, and the poor.”

Carolina also marks the passing of architect Harry Gesner, who designed prized homes across Southern California. Wave House, Eagle’s Watch, the Hollywood Boathouses, the Sandcastle — his idiosyncratic creations made the most of dramatic sites that sometimes were written off as unbuildable.

When The Times polled experts in 2008 and asked them to rank the best SoCal residential architecture of all time, the design that finished No. 1 was none other the R.M. Schindler’s King’s Road House, which celebrates its 100th birthday this year. Carolina checked out an exhibition diving into the history and legacy of a quintessential California retreat.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

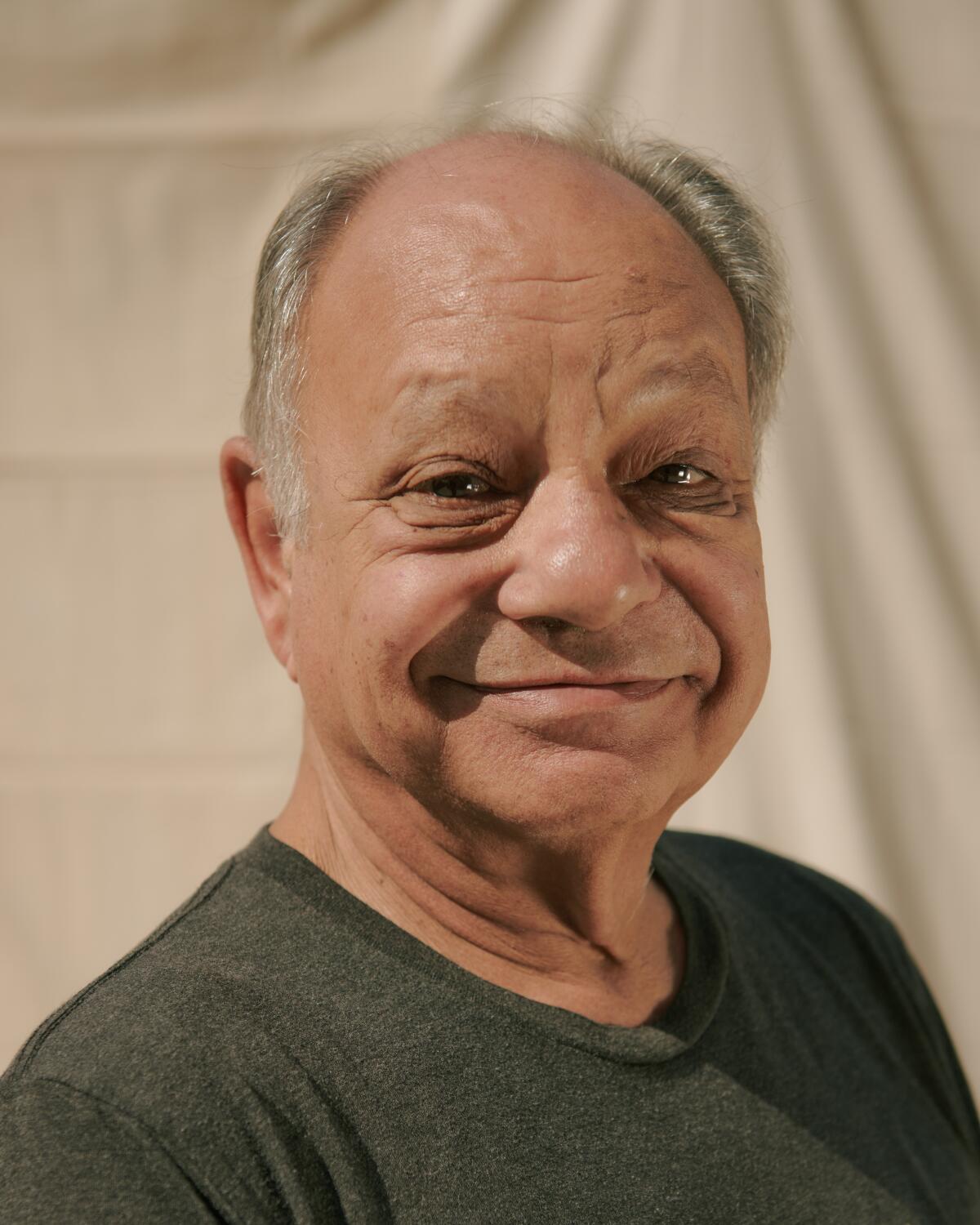

Meet the Cheech

It’s billed as the only permanent art space in America devoted exclusively to Chicano and Mexican American art. Yes, the official name really is the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture of the Riverside Art Museum, and yes, you can just call it “the Cheech” — please. In advance of the opening Saturday, The Times’ Melissa Hernandez got a peek at some of the 550 works from Marin’s personal collection on permanent rotation and talked to the museum’s namesake about how it came to be.

A stage set for change

The big headline out of the Tony Awards was the underdog victory for creator Michael R. Jackson’s “A Strange Loop” for best musical. “This victory is significant not only because this unapologetically Black, queer musical ... is a stunning artistic achievement,” writes Times theater critic Charles McNulty. “The show represents a breakthrough for what kind of stories can be successfully presented on Broadway stages.”

L. Morgan Lee lost her bid to be the first transgender performer to win Broadway’s biggest honor, but “A Strange Loop” producer Jennifer Hudson got her EGOT, reports Ashley Lee. And the understudies, swings and standbys who toil with little fanfare behind the scenes finally got a little love and appreciation.

Moving forward, the success of “A Strange Loop” provides hope for people of color aiming to break into that most rarified of theater clubs: producing. Lee talks to folks in the Theatre Producers of Color program, which is breaking down barriers to entry and building a new generation of theater leaders ready to push new stories and new faces onto stages across the country.

Catching up

Lisa Fung checks in with filmmaker Amy Rice, actor Jesse Tyler Ferguson and his husband, producer Justin Mikita, about how they captured the real-life drama of Broadway’s historic COVID-19 shutdown into the documentary “Broadway Rising,” which had its premiere at the Tribeca Festival.

Mark Swed wraps up the Ojai Music Festival, which, guided by American Modern Opera Company as music director, was by turns thrilling, mysterious, collaboratively comforting and startling confrontational.

Things to do

Matt Cooper has your best bets for the weekend, including Juneteenth celebrations in Leimert Park and Costa Mesa. You can find some additional SoCal options for Juneteenth in this magic map. And don’t forget our list of the best SoCal museum exhibitions in June.

While we’re on the subject: The Times is in the process of reinventing its listings of concerts, exhibitions, stage shows, festivals and more. Want to share your feelings about what kind of SoCal culture calendar would be most useful to you? Send your suggestions to calendar@latimes.com and we’ll incorporate your feedback into our planning.

And last but not least ...

The Times is launching a new portrait series celebrating Black culture in Los Angeles. It’s called “Behold,” and you can sneak a peek on Instagram before the big drop Sunday — in print as a multicover Calendar section package and online as a dedicated landing page within the Entertainment and Arts section.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.