Before the laptop came the mainframe. But did computers generate significant new art?

- Share via

I’m Times art critic Christopher Knight, filling in for newsletter regular Carolina A. Miranda, who’s out sandbagging in preparation for the Sierra snowmelt. As record winter blizzards give way to late-spring thaw, that likely disaster is just now getting underway. With threats of epic flooding predicted in pockets of California, here’s what’s happening in the arts avant le déluge:

The computer-themed “Coded” offers compelling social history without much worthwhile art

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Sometime in the late 1970s I did a studio visit at UC San Diego with Harold Cohen. Still new to California, I had heard about an artist working with computer programming to make experimental drawings and paintings, and I was curious to see more.

Since corporations and the military were then the primary users of computer technology, while personal computing was years away, the conversation was especially fascinating. I knew little, but British-born Cohen, self-taught in mainframe mysteries, knew a lot. Refining a complex computer program that the university professor invented with which to draw and paint seemed to represent a post-hippie desire: Wrestle the machinery away from the exclusive province of the military-industrial complex and instead put it to creative uses.

The problem: Every example of computer art I saw in the studio was unmemorable.

Cohen, who died at 87 in 2016, wasn’t able to produce machine-generated work that was more than rote. Tech seemed a focused way to drain the artist’s expressive self from a work of art, the subject of an emotional inner life having been wrung dry by the narrow, droning longevity of Abstract Expressionist painting. But that was a hurdle more inventively overcome by earlier Pop, Minimal and Conceptual strategies.

A few examples of Cohen’s work are included in “Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982,” a puzzling and largely inert exhibition currently at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Age has not improved them. A painting that assigned color-shapes according to a computer-coded schema is torpid, not ingenious. Visiting “Coded” was often like being in his studio all over again, although this time the context of a museum venue had the queasy effect of consecrating the general mediocrity.

To be sure, there is some wonderful art in the exhibition — many by artists well-known (Donald Judd, Edward Kienholz, Sol LeWitt, Bridget Riley and more); and some are by artists who are less familiar. Yet, the relationship between computers and these paintings, sculptures and drawings is either reed-thin or, frankly, nonexistent. The theme pursued in “Coded” is pretty much a shambles.

The closing date of 1982 represents the budding emergence of personal computing. The opening date — 1952 — reflects the moment typically identified as the start of digital art. Iowa mathematician Ben F. Laposky, then 38, tinkered with a cathode ray oscilloscope to produce black-and-white photographs. Laposky manipulated the amplitude, distortions and other properties of a lab machine’s electronic waveforms to draw luminous linear abstractions that swoop and pirouette across the sheet, their glow emerging from inky darkness. Permanent visual form is given to fleeting electrical voltage in electron beams.

These abstractions can be formally lovely, although Laposky’s repertoire of forms is rather limited. (Resembling a monochrome screensaver on a laptop, they have a “seen one, seem them all” quality.) The exhibition then immediately goes off the rails.

A 1968 abstract painting, four feet square, by Los Angeles artist June Harwood (1933-2015) layers curving sets of metallic-silver lines in two different widths against a gray background to create a visually rhythmic, light-reflective network of organic waves. Apparently, we’re meant to think “oscilloscope screen.”

Maybe. Except in the most superficial ways, however, Harwood’s work has roughly zero to do with engaging the emerging computer age.

Harwood is not widely known. She was a second-generation Light & Space painter, a talented artist married to Jules Langsner, the estimable L.A. critic who coined the term “hard-edge painting” in 1959 for artists like John McLaughlin and Lorser Feitelson. In her deceptively simple geometric abstractions, she was engaged in achieving complex spatial effects while using only the spare optical properties of composing with flat color.

That “Coded” doesn’t quite know what to make of Harwood’s art is evident from the catalog. Her handsome untitled painting gets a full page reproduction, but not a word is written about it in 272 pages of text featuring 18 otherwise often interesting essays by 14 different authors (including four by LACMA’s prints and drawings specialist Leslie Jones, the show’s curator).

Celebrated British Op artist Bridget Riley, on the other hand, whose parallel bands of rippling color in the marvelous 1964 “Polarity” are based on the curvy pattern of a sine wave, gets extensive catalog consideration. Oddly, we are told at length that scientific data, computation systems and mathematical theory are irrelevant to her work, which is another way of saying Riley’s painting has next to nothing to do with the “Coded” theme either. Nice painting — but why is it here?

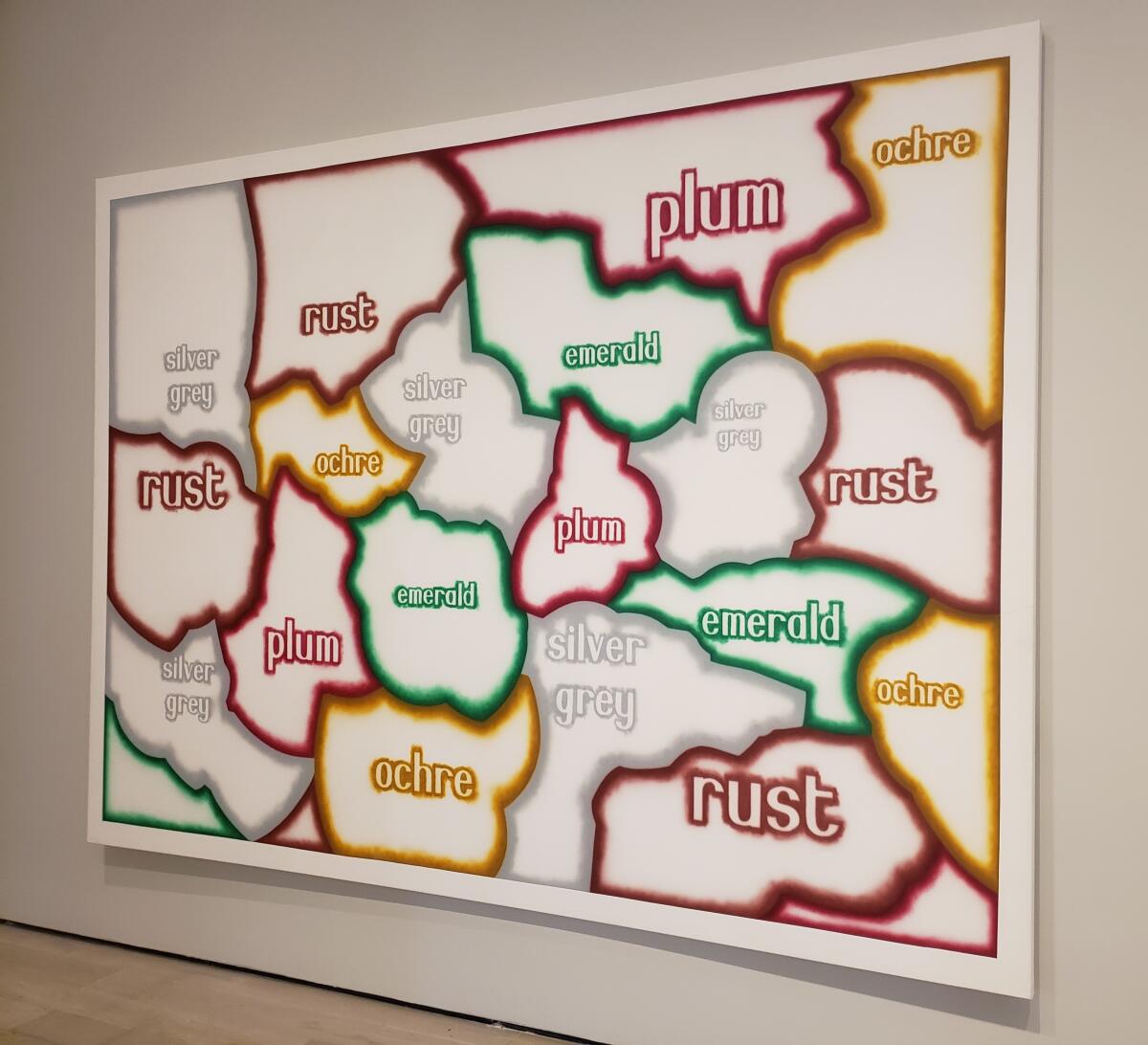

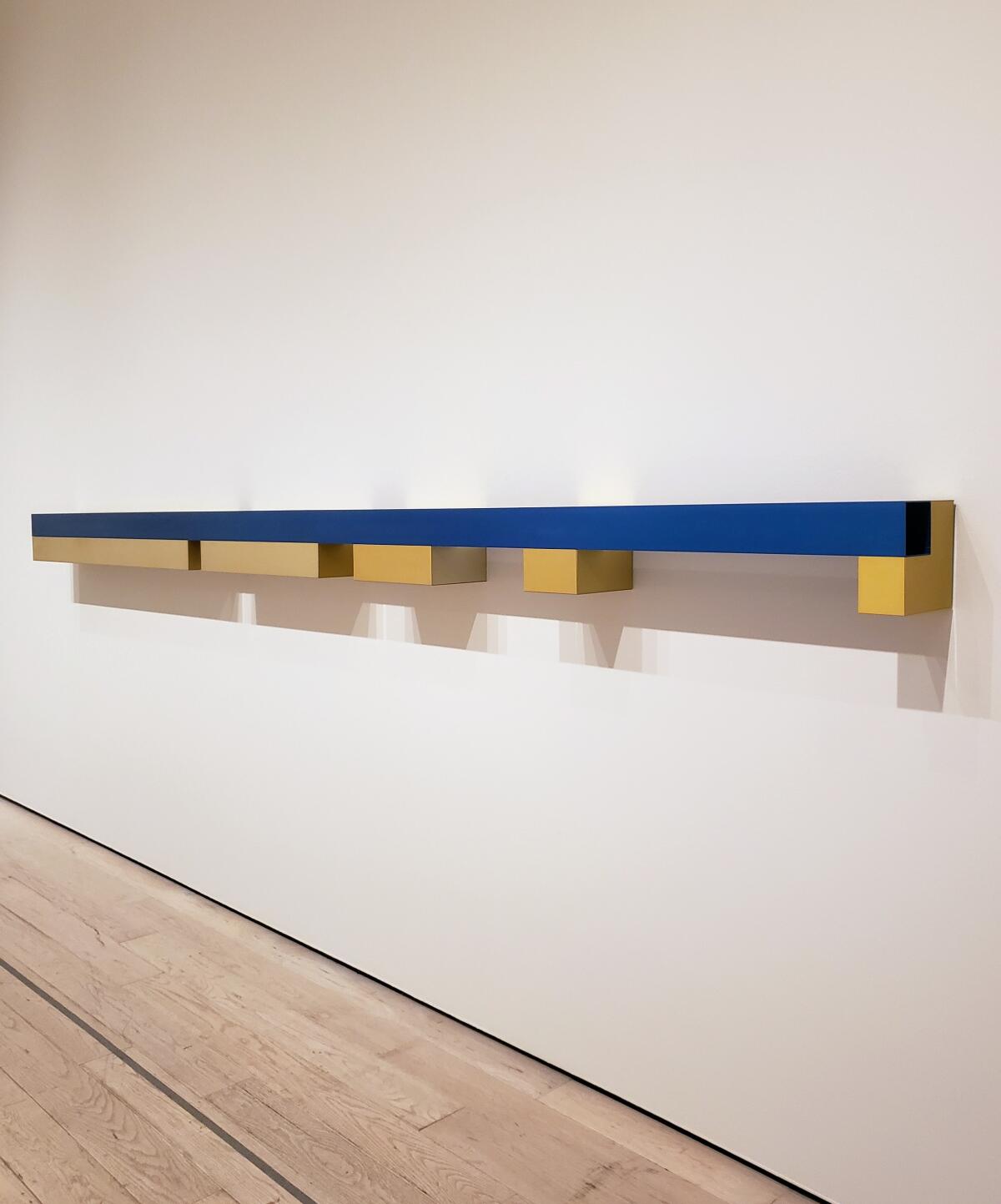

Minimalist artists who used mathematical principles in composition, like Judd and LeWitt, do get included. The arrangement in Judd’s 1971 “Wall Progression” sculpture of rectangular, blue and yellow anodized aluminum boxes — and the matching spaces flipped between them — derives from the Fibonacci sequence, in which each digit is the sum of the prior two: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, etc. LeWitt’s 1974 sculpture of “Incomplete Open Cubes” compiles all the ways to make a free-standing, three-dimensional form with sides of equal height, width and depth without ever making a complete cube.

What’s their relationship to computer coding? Merely that they all use mathematics, apparently. Well, so does the entire history of Western painting that employs the graphic systems of one- and two-point perspective — that choo-choo disappearing down railroad tracks or the building corner thrust toward you. Like Cohen’s algorithmic painting, the art of Judd, LeWitt and others labors against visual illusionism, so “Coded” tosses them into the stew.

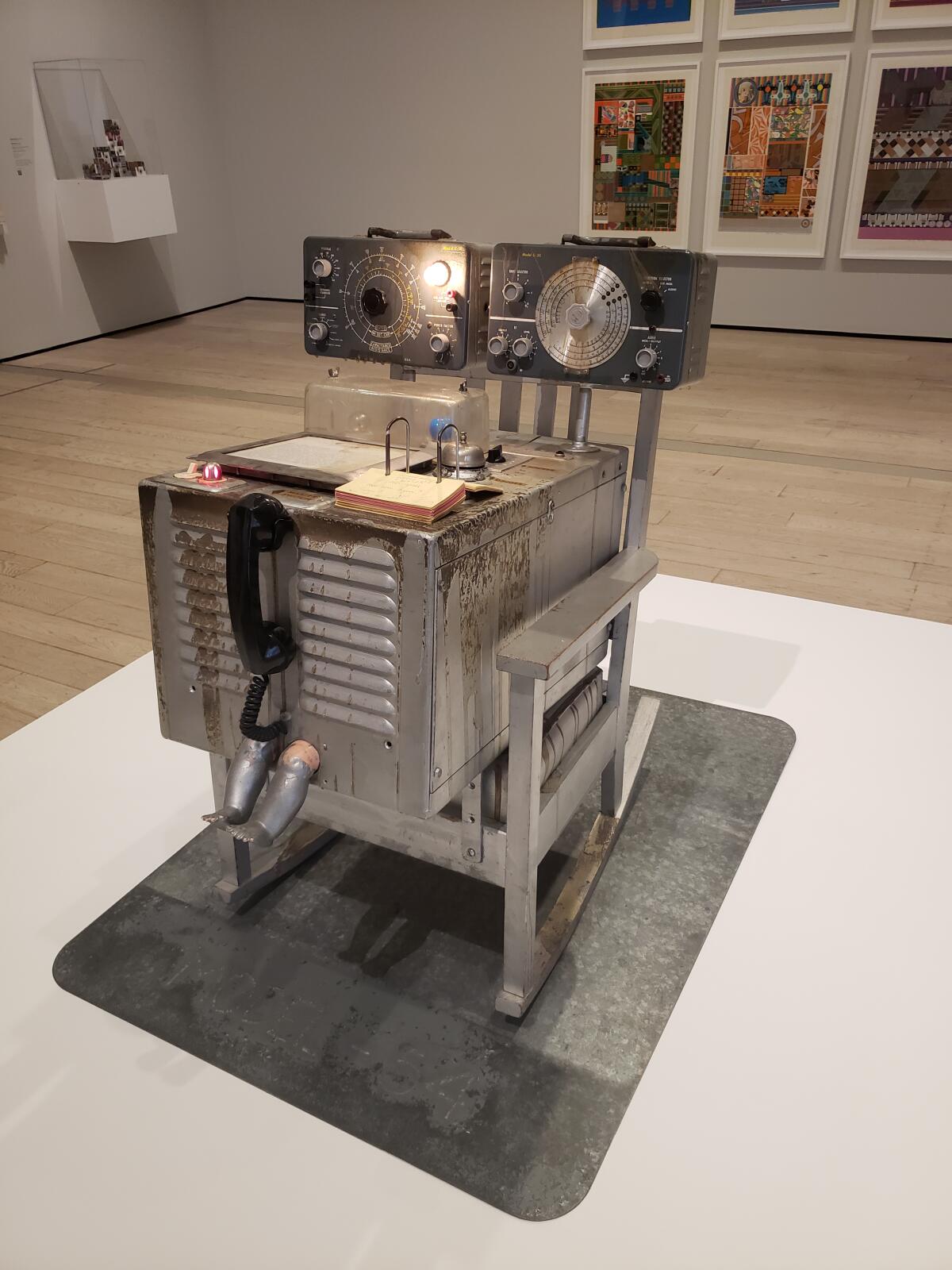

Ed Kienholz’s “The Friendly Grey Computer — Star Gauge Model #54,” one of only a few to directly address the digital environment, went straight for biting satire. The 1965 sculpture put a rusty workplace model of computer and some battered desk equipment into a cozy rocking chair, attaching instructions to give the poor overworked office machinery a periodic rest. (Doll-baby feet protrude at the bottom.) The computer age gets similarly overworked as the show’s theme.

This is one of those odd exhibitions effectively relaying an interesting social history that frankly produced almost no significant art. (Picasso said that, for art, computers were “useless. They can only give you answers.”) Last September, LACMA did something similar with “The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art.” The critical difference: The Korean show tracked what artists were up to, which made it meaningful, while “Coded” tracks the general culture, then overlays it on art.

Doesn’t work. Error404.

LACMA, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., (323) 857-6000, through July 2. Closed Wednesday. www.lacma.org

It’s Tony time

Broadway’s Tony Award nominations were announced Tuesday, with Jessica Gelt reporting that the musical version of the classic 1959 Billy Wilder movie “Some Like It Hot” took the lead with 13, while three plays tied for six each (“A Doll’s House,” “Leopoldstat” and “Ain’t No Mo’”). Scanning the lists, Times theater critic Charles McNulty observes that “the spirit of boldness that marked Broadway’s reopening in the wake of a once-in-a-century pandemic and widespread societal reckonings on equity, diversity and inclusion was still apparent, though bottom-line realities aggressively reasserted themselves.” Two steps forward, one step back. Among the forward steps, reports Ashley Lee, are nods for J. Harrison Ghee and Alex Newell, the first nonbinary-identifying actors to be nominated for Tony Awards.

McNulty also caught David Lee’s production of Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler’s “A Little Night Music” at the Pasadena Playhouse, and he has just one question for star Merle Dandridge: “Where have you been all my theatrical life?” Read about why McNulty dubs her performance “a musical theater dream come true” here.

And writing from New York, McNulty took in “Prima Facie,” the one-woman Broadway play starring Jodie Comer that charts the way the judicial system puts rape survivors through the wringer. He notes: “It’s an ideal guide for understanding what E. Jean Carroll is up against in the civil trial against Donald Trump, whom she has accused of raping her in the mid-1990s in a New York department store.”

Mediation, please

When multiple artists work as a collective, deciding who did what, when and where, who controls the legacy and — not least — who holds the copyright can be a tad thorny. ASCO, the important Chicano artists collective that helped to define art in 1970s Los Angeles, has tussled over those issues for years. And they still are, as Times art and design columnist Carolina A. Miranda discovered when she discussed it with Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk (Glugio Nicandro), Willie Herrón III and Patssi Valdez. The infighting continues.

The subject as artist

Spanish court painter Diego Velázquez’s brilliant, circa 1650 portrait of his enslaved studio assistant Juan de Pareja is one of the great treasures of European painting in the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pareja — a Morisco man from southern Spain, and an artist in his own right — is currently the subject of an unprecedented Met exhibition of his life and art. David Pullins, co-curator with biographer Vanessa K. Valdés of “Juan de Pareja: Afro-Hispanic Painter in the Age of Velázquez,” has a lot to say in an interview with historian Tyler Green for the Modern Art Notes podcast.

Exploitation of enslaved studio workers was common in 17th century Spain — which raises an intriguing question: As an artist, to what degree might Pareja have been engaged in the workshop aspects of painting Velázquez canvases? Don’t miss the commentary on Pareja’s own monumental 1667 painting, “The Baptism of Christ,” which the curator astutely describes as frankly “wild.”

The book bag

Just announced in the Getty Museum’s ongoing Illuminating Women Artists series of monographs, publishing in partnership with the UK’s Lund Humphries, is the June release of books on Italian Baroque painter Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665) and Venetian portraitist Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757). They’re the first English-language publications on two artists not widely known now but famous in their day.

If you forgot to buy advance tickets for “Vermeer,” the pack-’em-in exhibition of the hugely famous Dutch painter, winding up in a month at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, you are flat out of luck. Unless you can track down a trustworthy scalper — a contradiction in terms? — they cannot be had anywhere, online or at the museum. Next best is the catalog by Pieter Roelofs and Gregor J.M. Weber, its English edition arriving in about a week from Thames & Hudson. Synthesized recent scholarship meets extensively detailed photographs (200 of them!) of all 28 paintings in the show, seven more than were in the 1995 Washington, D.C., blockbuster at the National Gallery of Art. (Only about 35 Vermeers are thought to exist.) Nice.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Moves

- California Arts Council’s Individual Artist Fellowships provide unrestricted funding in support of artistic practice. Applications for three fellowship categories — emerging ($5,000); established ($10,000); and legacy ($50,000) — are due June 2.

- The juries for the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts have announced 10 prizes to 11 artists for 2023 in dance, theater, music, film and video, as well as visual arts — the last to the pseudonymous American Artist and Park McArthur. Each award carries an unrestricted prize of $75,000.

- The Ellsworth Kelly Foundation has awarded $2.75 million in grants to 50 American museums in honor of the artist’s centennial (Kelly died at 92 in 2015). The artist’s widower, photographer and foundation president Jack Shear, also made targeted donations of Kelly’s works on paper from his collection to amplify museums’ existing holdings. Southern California recipients of the largesse are the Broad museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego and Norton Simon Museum. Locally, centennial exhibitions are planned of Kelly’s lithographs at Gemini G.E.L. and photographs at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

Passages

Aerial landscape painter Yvonne Jacquette died of a heart attack on April 23 at her home in New York City. She was 88.

Thomas Kong, a Chicago collage artist who filled his Rogers Park convenience store with work pieced together from package wrappers and shopping bags, has died at 73.

L.A.’s Fountain Theater co-founder Deborah Lawlor has died at 83.

Essential happenings

In the L.A. Goes Out newsletter, Steven Vargas recommends Thornton Dial’s first major solo exhibition in Los Angeles, at Blum & Poe — plus lots more.

And Matt Cooper, fresh off rigorous Cinco de Mayo duty, maps the culture guide to theater, movies, dance, classical music, museums and more.

In the news

- A production assistant on the HBO Max drag series “We’re Here” has accused reality star Darius Jeremy (DJ) Pierce, who goes by the stage name Shangela, of sexual assault. Pierce has strongly denied the accusation.

- Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum is reportedly considering loans of two Parthenon fragments in its collection to the Acropolis Museum in Athens. One depicts two young riders, and the other shows heads of two processional figures with olive branches, known as thallophores.

- Is the Conglomerado Atelier do Centro, an art school in São Paulo, Brazil, actually a cult? Some students say yes.

- The Alice L. Walton Foundation, Ford Foundation, Mellon Foundation and Pilot House Philanthropy have joined forces to commit $11 million over the next five years to increase racial equity in leadership positions in 19 museums, including L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art and the Riverside Art Museum. Participants have pledged to make positions permanent when the initiative’s five-year funding cycle ends.

And last but not least ...

New York’s Met Gala fashion fundraiser jumped the shark eight years ago, when the massive train on Rihanna’s fur-trimmed, canary-yellow Guo Pei gown became a social media meme-a-palooza — the most memorable being a digital image merging it with a giant pepperoni pizza. This week saw assemblage artist Willie Cole expressing reasonable Twitter fury at the 2023 Gala set design’s chandeliers made from recycled plastic bottles — a near-signature motif the New Jersey-based sculptor has been using for a decade. (A “blatant rip-off,” he said, with some justification.)

But the social media fan favorite had to be the actual cockroach photographed among the glamazons climbing the august museum’s grand staircase. Maybe it was looking for pizza? Whatever, when a fundraiser snags $17 million, as the schlocky Met Gala did last year, what are a few bugs?

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.