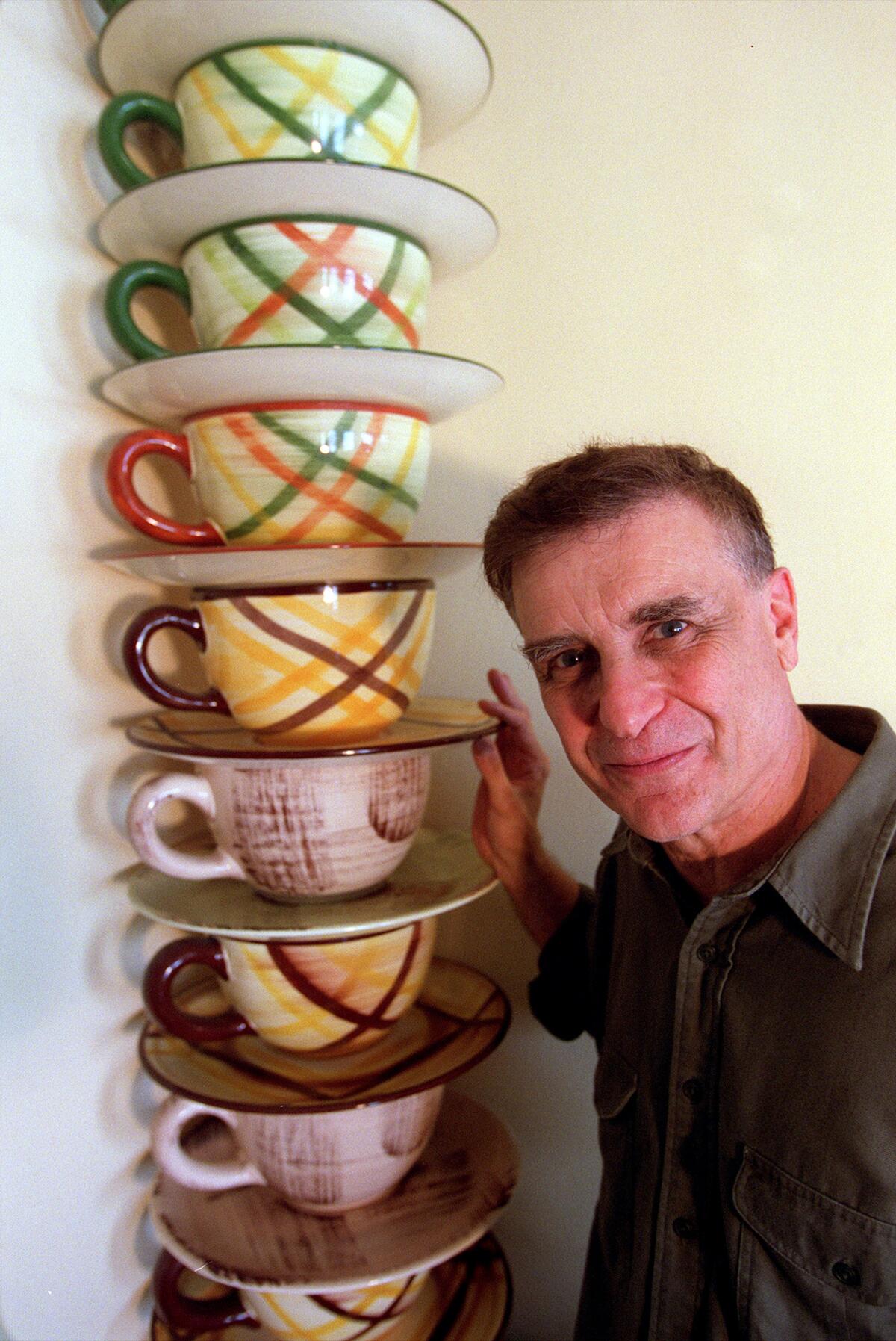

Bill Stern, champion of California ceramics, is dead at 78

- Share via

Bill Stern, the energetic Los Angeles food critic turned curator who went on to found the Museum of California Design, a pop-up curatorial project that examined the underexplored corners of California design, including design by women, has died at 78.

Stern, whose death was confirmed by the museum’s chief financial officer, Michael Michaud, died in his sleep of unknown causes in his Los Angeles home on Saturday.

For the record:

5:59 p.m. March 14, 2020An earlier version of this story reported that Bill Stern was 79 at time of death. He was 78.

With Stern’s death, says Michaud, the design world has lost a font of information about California industrial design — Stern’s primary area of interest was commercial ceramics. “I don’t know who else had the kind of knowledge he did.”

Over the course of a peripatetic career — which included a stint as a park ranger in Alaska, a period spent dubbing Hollywood films into different languages and numerous years as a restaurant critic for The Times and the L.A. Weekly — it was California pottery that would become his greatest obsession.

And it began with collecting. In 1981, he acquired his first set of dishes — bright Vernonware, made in Vernon — from a porn star neighbor who was moving away. That sent him down a rabbit hole of flea markets and estate sales in search of what Stern once described in a 1994 interview as, “Mmmore, mmmore.”

Michaud, a long-time friend of Stern’s, recalls a home stuffed with ceramics.

“Plates, bowls, lamps, everything you could think of,” he recalls. “The house was packed, from the floor to the ceiling. You’d open a cabinet and it would be stacked with plates in every color of the rainbow from Bauer,” the firm known for the colorful lines it first produced in the early 20th century.

The collecting habit ultimately led Stern to curating.

In 1999, he established the Museum of California Design as a way to organize a range of programming on the topic, including numerous exhibitions staged in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Palm Springs. Among the more notable shows Stern organized was “California Pottery: From Missions to Modernism,” which was displayed at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2001, before traveling to L.A.’s Autry Museum of the American West two years later, as well as the 2012 group show “California’s Designing Women, 1896-1986,” also shown at the Autry.

The latter exhibition featured more than 200 works by 46 female industrial designers from California. These included established figures, such as housewares designer Gere Kavanaugh, as well as those who were virtually unknown, including Wilmer James, an African American designer of earthenware whose work had never before been displayed in a museum.

Jeff Weinstein, a New York-based arts journalist (and long-time friend of Stern’s) who edited the catalog for the exhibition, says the show helped create a record of work by women that may have otherwise been forgotten.

“It was was a personal victory for him to interview women who were fine women and fine designers who were hidden and still alive in L.A.,” he says. “Many of them were in their eighties and nineties, and he got the story. It was a fabulous show.”

When LACMA presented its “California Design, 1930-1965: ‘Living in a Modern Way’” exhibition, part of the 2011 Pacific Standard Time series, Stern was not only a consulting curator, many pieces from his own collection were included in the show.

Cobb died this week at 93. His U.S. Bank Tower, formerly the Library Tower, upgraded Los Angeles’ previously dull downtown skyline.

William B. Stern was born May 13, 1941, in New York City to a doctor father and an artist mother. For his undergraduate studies, he went to Alaska, completing his Bachelor of Arts at the University of Alaska in 1964. During that time, he also worked as a park ranger.

“He told me a lot of stories about living on salmon he would catch and canned goods people would drop by parachute,” Weinstein says.

In the late 1960s, Stern returned to New York to study comparative literature at Columbia University.

He moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1970s, landing a job at Warner Bros, where he deployed the various languages he had picked up in college in the field of film dubbing — helping to produce scripts and hire voice actors to translate films for European release.

Yaro tutored the actor who played Animal, the rumpled photographer on “Lou Grant”

In the 1980s, he began pursuing food criticism, writing restaurant reviews first for the Los Angeles Reader, followed by the L.A. Weekly and The Times. At the latter, he showed an interest in a wide variety of food, reviewing a Russian banquet hall, a Western steakhouse and a Barcelona-style bistro.

In a 1990 story titled “The Offal Truth,” he sung the praises of offal in a city where he felt not enough restaurants served it: “Although chicken livers and gizzards are as rare as hens’ teeth in these parts, you can find them fried at some Pioneer Chicken outlets.”

In another story, he described biscuits and gravy as “one of the gummy horrors of American country cooking.”

By the end of the 1990s, more than a decade after acquiring the fated dishset from his neighbor, he was curating entire shows on ceramics. But he was always most interested in the ceramics produced in California, ever protective of the state’s contributions to design.

In 2001, a journalist writing about the “California Pottery” show at SFMOMA asked him about Fiestaware, the Virginia-made ceramics that filled U.S. kitchen cabinets with bright colors in the late 1930s, at a time when most china was white.

“It’s a rip-off,” said Stern. Fiestaware was a California idea, he told the interviewer. “The rest of the country was aesthetically still an extension of Europe — ivory china with intricate floral patterns around the edges.”

“Part of my role,” he told a writer for this paper in 2003, “is to transmit this knowledge of a heretofore unacknowledged part of American culture. I firmly believe that every human being has to be taught that what they see wasn’t always there.”

Stern is survived by his cousin Margaret Stern, who lives in New York.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.