This church was vital for L.A.’s Chicano movement. Now it’s getting the landmark status it deserves

- Share via

A Lincoln Heights church with vital ties to the Chicano civil rights movement of the 1960s has secured a spot on the National Register of Historic Places — bringing formal recognition of its status as a landmark worthy of protection.

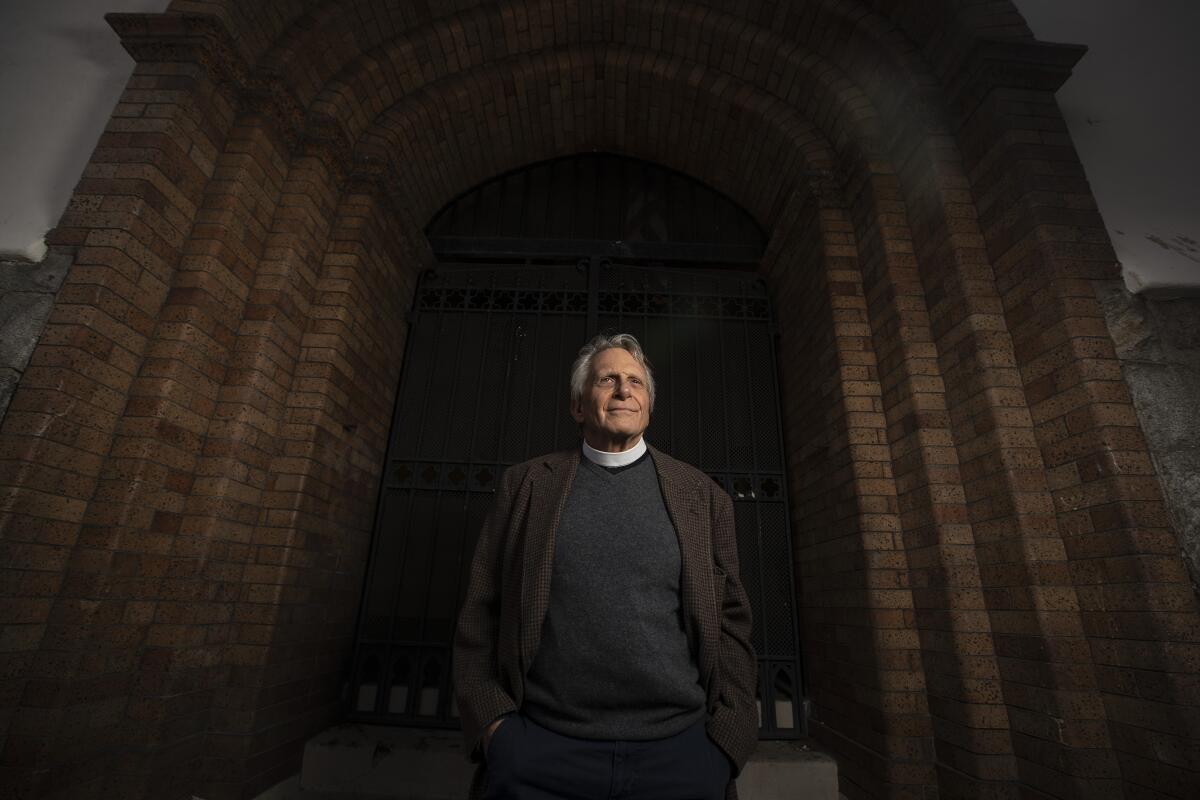

The Church of the Epiphany — built in 1887 and revered as the oldest operating Episcopal church in Los Angeles — announced the honor this week as part of a push to raise funds for a restoration project that includes rehabilitating the basement, where much of the community organizing and activism took place.

“That is the legacy of this church,” said Father Tom Carey, the church’s vicar, in a recent phone interview. “It is a place where people have spoken up.”

The National Register designation is made all the more noteworthy because, according to Los Angeles Conservancy President Linda Dishman, only 10% of the city’s 1,203 historic-cultural monuments are associated with women or with BIPOC or LGBTQ communities. Nationally, according to National Register statistics, that percentage is less than 8%.

The emphasis for qualification, said Dishman, has long been on architecture as opposed to culture and history, but that is slowly starting to change. Evidence of the shift was marked last year when key sites along the march routes used by demonstrators with the Chicano Moratorium were listed on the National Register.

The Chicano Moratorium, which protested the Vietnam War and its toll on Mexican Americans, used the Church of the Epiphany as a gathering place for planning and discussions. La Raza, a newspaper published by Chicano activists, employed the church basement as its editorial headquarters. Youth leaders met in the basement to organize the East L.A. student walkouts, which called for more inclusive representation in school administrations and safer, more equitable campuses.

Rosalio Muñoz, 74, a key organizer of the Chicano Moratorium, grew up in Lincoln Heights and was a Cub Scout at the church during what he calls his “little rascal” phase of life, before the draft, the war and activism strengthened his bond with the church and those who used it as a home base for worship and social justice. Until the recent renovations, Muñoz kept an office at the church, using it to gather and catalog pamphlets, photographs and other archival ephemera related to the church’s civil rights history.

Muñoz is a living encyclopedia of that history, reciting off the top of his head the names of prominent organizers tied to the church, and tracing the lineage of its activism back to the 1940s. The success of the church as a hub for social justice, said Muñoz, came because those involved knew that “the community has to have its own voice in order to be active with its own culture.”

History echoes through places, and buildings tell stories, Dishman said, which is why recognition on a national level matters. The importance of the church is known to the neighborhood and its community, but having it on the National Register ensures that its story — and that of L.A.’s Chicano Movement — is recognized far beyond the city.

The basement is, in many ways, the heart of the church, yet it has been used as a glorified storage space for decades, said architect Frank Escher, who with partner Ravi Gunewardena has been working on restoration projects at the church for more than a decade.

The church, which never ceased being a focal point for social activism, doesn’t have a lot of extra space, so making the basement a place where activity can again occur is essential to its commitment to the community going forward, Escher said.

The original brickwork has been exposed, as have some beautiful redwood beams and a long-forgotten window, Carey said. A meeting and exhibition space are being added, as are several offices.

“The church is almost in original condition,” Escher said. “Its original interior, plus this incredible social and cultural history, make it a very unusual place.”

The added functional space will enhance the church’s ability to continue social-justice work. In recent years, activists at the church have brought supplies to refugee centers in Tijuana, accompanied people to immigration court, walked picket lines in support of protections for grocery-store workers during the pandemic, been active in HIV testing and education, hosted the Eviction Defense Network for free legal advice and more.

The Church of the Epiphany’s past importance, combined with its present commitments, appeals to groups that have helped to fund its renovation over the years. Those groups include the National Fund for Sacred Places, which works in collaboration with the National Trust for Historic Preservation to support historic houses of worship that, according to its website, “contribute significant value to their communities.”

Allison King, the grants program manager for Sacred Places, said the Church of the Epiphany received the program’s highest award of $250,000, which is doled out as a matching fund — $1 for every $2 raised by the congregation. The year the church applied, it was one of 15 winners selected out of nearly 300 applicants.

“They do such a diverse amount of programming,” King said. “They host so many different groups, and their art shows and concerts are quite special.”

Artists have flocked to support the Church of the Epiphany for many of the same reasons preservationists have. In 2014, an auction featuring the work of nearly three-dozen artists, including Barbara Kruger, Fritz Haeg and Corita Kent, raised funds to further restore the building, including four stained-glass windows.

More than 60 artists, including those who organized at the church decades ago, contributed to a 2018 exhibition at the church titled “The Art of Protest: Epiphany and the Culture of Empowerment.” Art lends itself to the natural beauty of the structure, which maintains noteworthy architectural significance in the city.

The original building of the late-1880s Church of the Epiphany was designed in the Romanesque Revival style by the English architect Ernest Coxhead. Membership grew, and by 1913 more space was needed. Arthur Benton, known for his work on Riverside’s Mission Inn, created a new structure using a variety of revival styles including Gothic, Mission and Romanesque. The existing church was incorporated into the new building and converted into the parish hall.

Over the years, Lincoln Heights transformed from a white enclave to a working-class Latino neighborhood. Today the church sits on a quiet residential corner, nestled snugly against two single-family homes, and across the street from a blocky, modern apartment building. Construction is ongoing and services are remote, but a large banner still notifies the public of an operating food bank.

“The pandemic has really shaken up our idea about what constitutes church and community,” Carey said. “Because we haven’t been able to meet in person since March.”

The pause in services, however, will allow the renovations to continue at a decent clip. To date, the church has raised nearly $750,000, and it hopes to hit $1 million soon. When this last fundraising push is over, and the fog of coronavirus restrictions lift, the community will welcome a historic church made more resilient than ever.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.