‘Crouching Tiger’ composer Tan Dun will give L.A. Phil a martial-arts workout

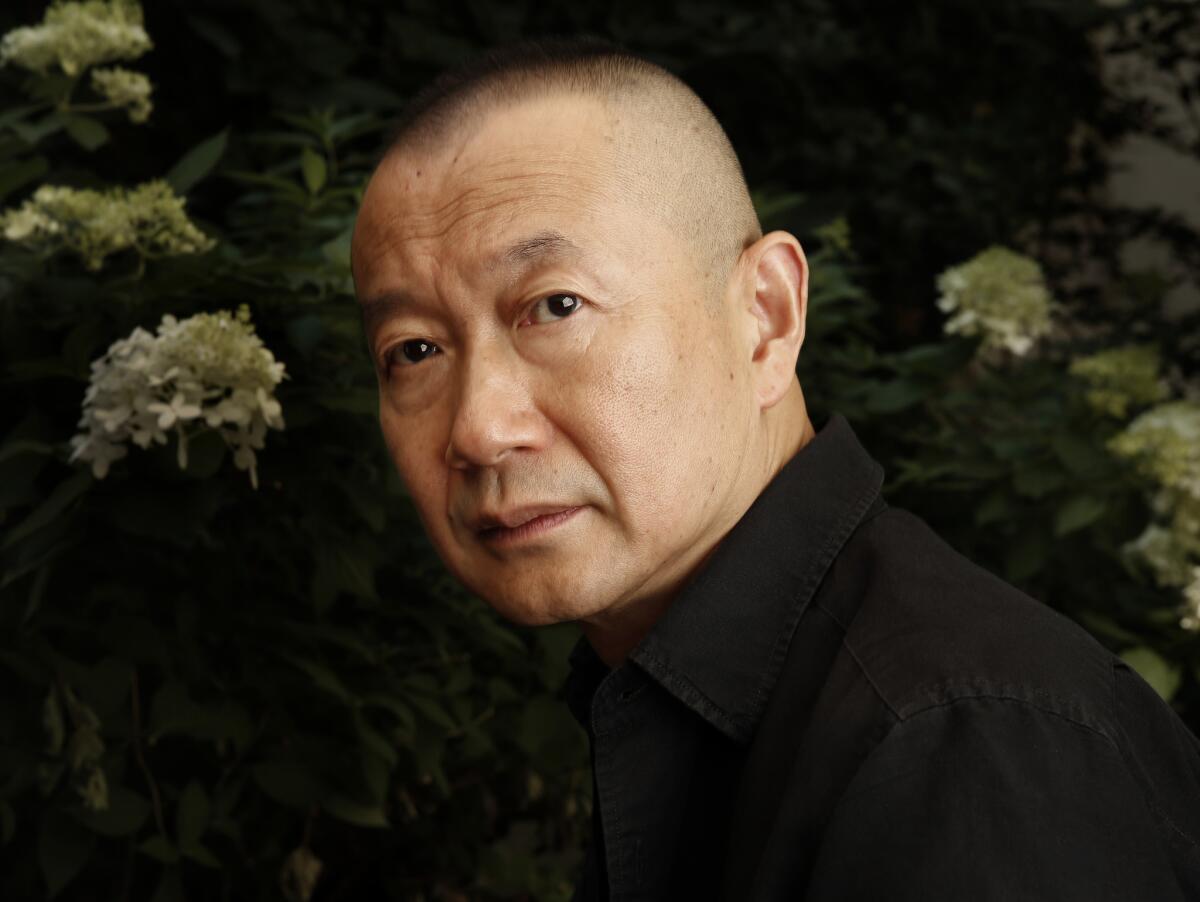

Composer-conductor Tan Dun at his home in New York City in July 2015.

- Share via

Tan Dun is a composer of many sounds. He has coaxed birdsong from cellphones and is intimate with the pipa, the ancient Chinese lute. At once global and local, he is an old soul tuned to modern fascinations, mixing Asian and Western styles that fit as well into cinema as they do the concert hall. Tan won the Academy Award for his score for Ang Lee’s martial arts film “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.” He will conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic on that score and music from two other films as part of his multimedia “Martial Arts Trilogy” at the Hollywood Bowl on Aug. 13.

You have said that your “Martial Arts Trilogy” program was inspired by Richard Wagner’s “Ring” cycle of operas.

The trilogy is a cinema- and opera-linked concept. Opera is ancient cinema. The love, hope, dream, fighting, revenge and soul themes are very much like Wagner’s “Ring” cycle. All the themes come jumping together. I used the river and water theme as a base to link the “Crouching Tiger” dream theme, the “Hero” hope theme and “The Banquet” love theme to all come back as a super trio.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

Orchestras are struggling to reach new and younger audiences. But are they being experimental enough, especially when it comes to multimedia?

Everyone is trying to do something with image and sound. But in most cases they use images as a complement to sound and sound a complement to images. But a multimedia show should focus on a synchronization of color and timbre that becomes so powerful. If you see Martial Arts Trilogy you will see everything is synchronized. The music should be the most dramatic, the most operatic and meanwhile we use image and story to the best multimedia effect.

You grew up during China’s Cultural Revolution and now live in New York and Shanghai. You conduct and perform around the world. How has globalization influenced how classical and other forms of music are composed, presented and listened to?

It doesn’t matter if it’s globalization or nationalism. You have to have drama, theater and the visual. The rest of the things are actually pretty much practical orchestration or stylistic kinds of things. It’s like Federico Fellini. I love Fellini’s films. His work is Italian, but it talks to everybody. It’s very global, dramatic and visual.

How can composers incorporate the sounds of different cultures to bring people together?

The composer or artist has to be trained in various techniques. The Western orchestra technique or maybe the media or computer technique. They must have a strong knowledge of Eastern or African or Aborigine or indigenous sound worlds. If you are trained, you can put something very powerful together. It depends on technique and philosophical needs and how culturally trained you are.

Your new composition, “Passacaglia: Secret of Wind and Birds,” was recently performed in Carnegie Hall by the National Youth Orchestra of the United States of America. You used mobile phones to create birdsong. What inspired this?

The ancient instruments always started with the birds singing. I was thinking for a long time if I wanted to turn social media or the cellphone into an instrument. If you’re using hundreds of cellphones to play this ancient instrument of birds singing, it’s really like an unbelievable forest of sounds. This convinced me that the cellphone could be an instrument in today’s symphony orchestra. The question is how to transpose the digital birdsong into the orchestra. It’s a miracle. It’s so fun.

You’ve characterized China as taking a long nap from the international community following the end of the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s. Today, China is emerging as a global economic power. What are your thoughts on where your native land is headed culturally and in other ways?

When I was young I experienced this very bloody revolution, almost every family was broken. This made me think of human beings, of life, the future. People ask me why my music has that haunting or lonely or kind of melancholia [quality]. Maybe this is from early childhood or a Cultural Revolution suffering memory. But now China is waking up as a new force for culture, specifically for classical music.

You really feel China is going to be the home of classical music. Every month there’s an opera house or concert hall debuted. Thirty million kids are studying piano and 25 million are studying violin. And every day in Europe and America we are shrinking orchestras, shrinking budgets. But in China, government funding is growing year by year.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.