Review: Pancho Villa and the Hubble Space Telescope go on operatic adventures (and the ride gets bumpy)

- Share via

As a genre, the Old World art form of opera lost its rigidity in the New World long ago. Even rock opera has a kind of geriatric connotation these days, when anyone and everyone is invited to make opera into anything they like.

That was certainly the case with back-to-back West Coast premieres of new, loosely operatic works, in what would once have seemed unlikely venues, by what are sometimes known as “alt-classical” composers. The target audience has also changed, with shows hoping to be as alluring to a youngish, hip-ish, social media-savvy crowd as the next hot downtown restaurant.

Tuesday night at the Theatre at Ace Hotel, the Los Angles Exchange [LAX] Festival presented “Pancho Villa From a Safe Distance.” The Austin, Texas-based composer Graham Reynolds is a rock and jazz band leader, film composer (notably for Richard Linklater), collaborator with various dance and theater companies and director of Golden Hornet, called “a composer’s laboratory for the 21st century.”

Then on Wednesday, “The Hubble Cantata” came to the Ford Theatres, co-presented by Los Angeles Opera as part of it’s Off Grand series. Paola Prestini is also a genre-bending (if somewhat more traditionally classical) composer and entrepreneur who runs National Sawdust, the fashionable new music venue in Brooklyn.

Although quite different musically and theatrically, the two “operas” have enough in common to speak of a shared zeitgeist (so much so that Prestini will be participating in a future Reynolds music theater project). Both pieces are for two singers. “Pancho Villa” is essentially a pop song cycle. “Hubble,” which might be called an opera/cantata, also is made of separate numbers.

Both use multimedia — film in the case of “Pancho Villa” and virtual reality for “Hubble” — as a hook. They favor loud amplification. They are musically and visually accessible but get fancy with narrative.

Indeed, it is mainly in the two librettos where operatic pretension becomes a problem. If you don’t know much about the Mexican Revolution or astrophysics, you won’t have an easy time following these works. The idea seems to be that one way to impress the audience is with obscurity.

Another curious coincidence is that the two librettos are structured around a search for meaning. In the case of “Pancho Villa,” a 19-year-old student is trying to find in the life of the famed Mexican Revolution figure some answers to current social and political problems in Mexico. The teen is an extra-musical figure, presented documentary-style on film.

Around that are incidents from Villa’s life, shown visually and sung, with fanciful lyrics by Luisa Pardo and Gabino Rodriguez of the Mexican theater collective Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol. The two soloists, Paul Sanchez and Liz Cass, though, are the heart of the show, both terrific in conveying Reynolds’ comfortable Tex-Mex mix of rock and Mexican musical styles with a hint of Broadway. The quirky quintet of violin, cello, electric guitar, bass (alternating with tuba) and drums led by Reynolds on the synthesizer provide the pop moxie of what would ultimately make an excellent album’s worth of songs about Pancho Villa.

The fascinating image that inspired Reynolds was that of high-society American tourists who stood on the roof of an El Paso hotel to watch through opera glasses the Mexican Revolution as it was being fought across the border. And the fascinating lure for “The Hubble Cantata” is that opportunity to don virtual reality gear to spy on the Orion Nebula.

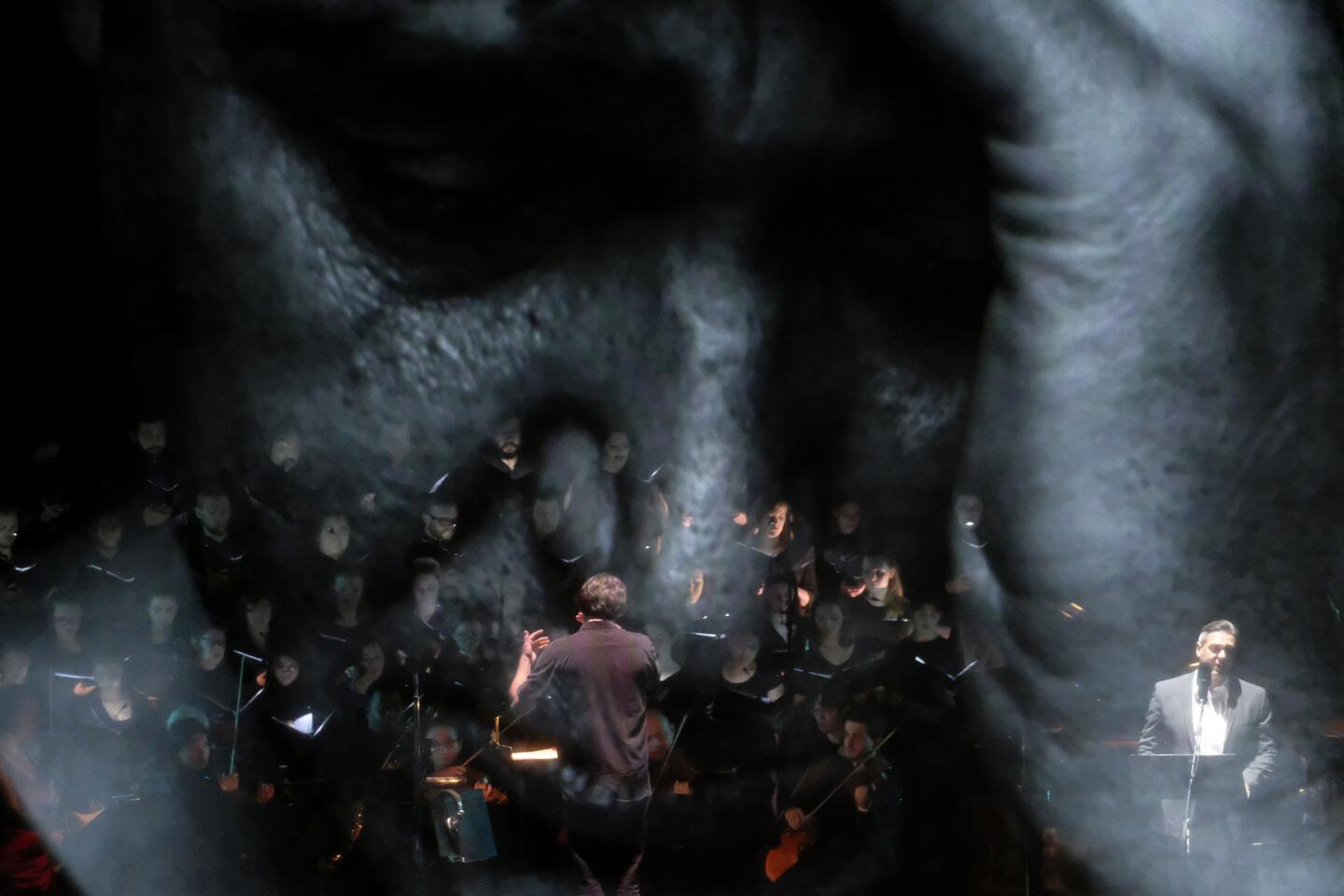

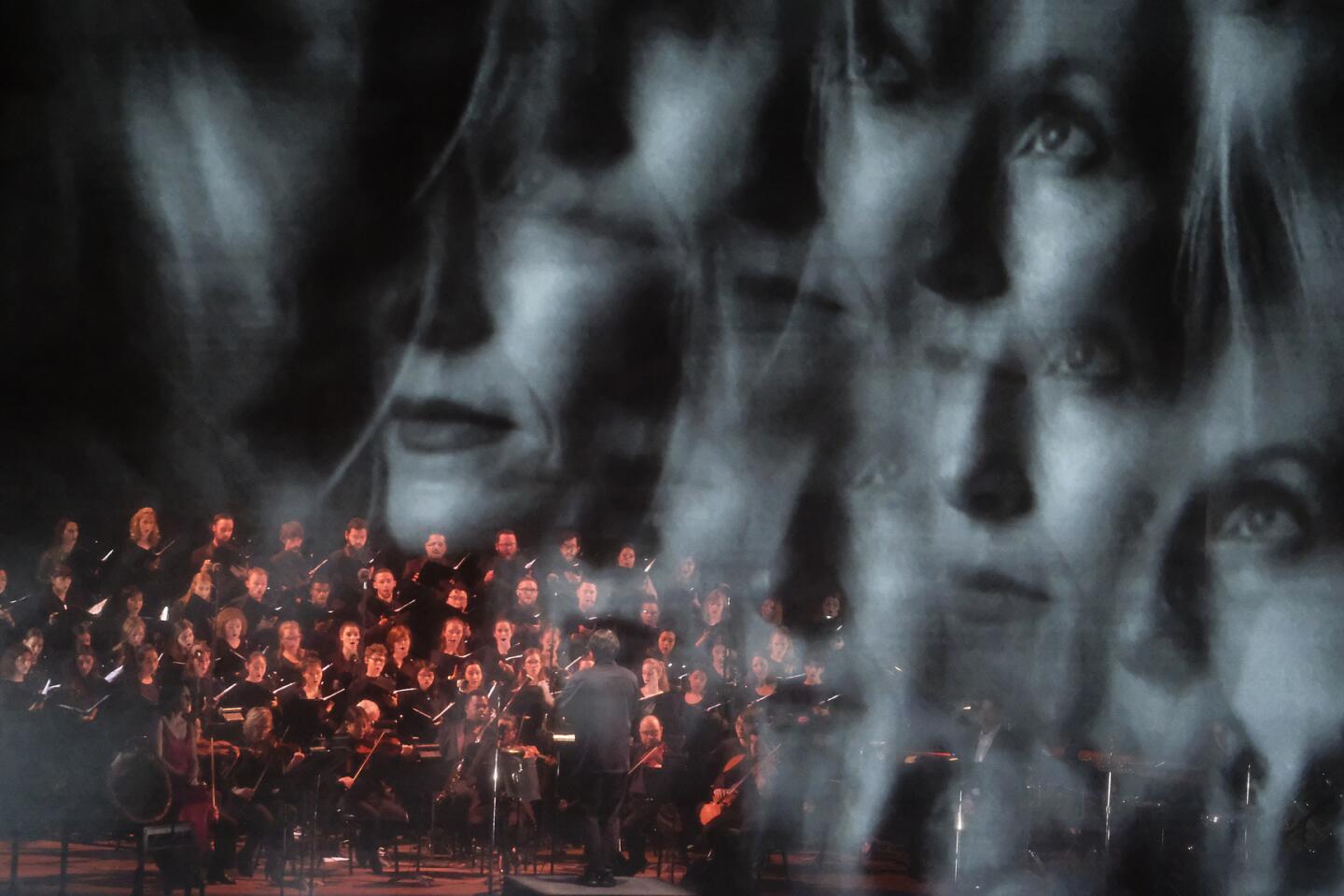

But here, there is even less in the way of real theater. Two first-rate opera singers, Jessica Rivera and Nathan Gunn, stood in front of music stands. Behind them were what were called the L.A. Opera Orchestra and Chorus (but including no regular members) and the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus, conducted by Julian Wachner.

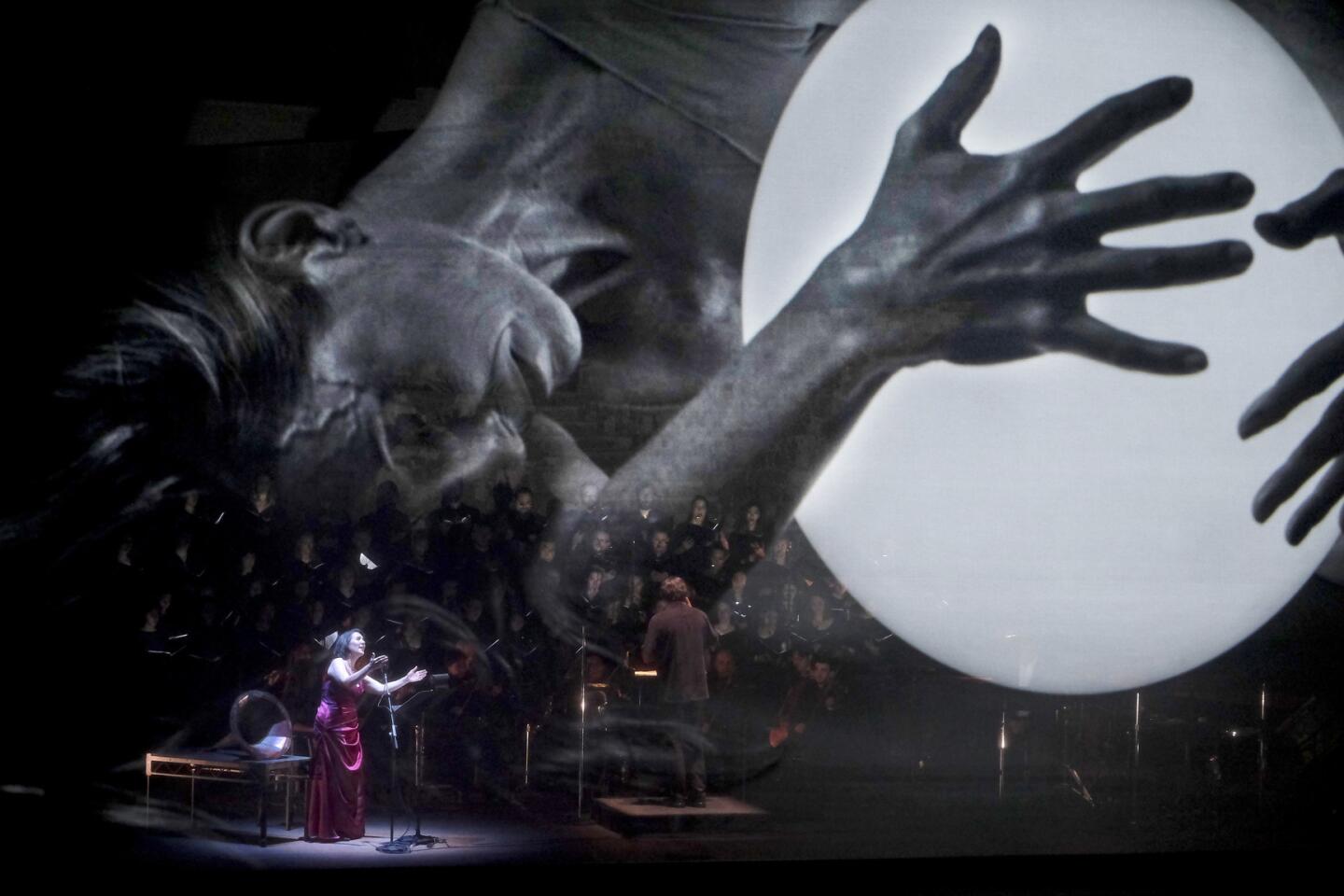

On a giant scrim in front were projected images of the universe and a woman lost in it. She is meant to be the wife of an astrophysicist who has committed suicide after the death of the couple’s child. Answers to life’s great and terrible meaning are sought in the sky above. A guide is the physicist and popular author, Mario Livio, who adds recorded narration (although he could have done it more effectively live on stage, since he was present for a pre-performance talk).

For the last 10 minutes of the 55-minute work, we were expected to have downloaded an app on our phones, which we then used with supplied virtual reality gear to have a 3-D look around at the Hubble telescope floating in space and what it sees beyond. Our bodies being nothing more than star dust, we become one with the great beyond. The score begins and ends with the choruses singing “Lie in the grass … Collect your stars.”

As an opera/cantata, at least as presented at the Ford, the “Hubble” was a mess from start to finish. It is hard to say much about the music, because the Ford’s new sound system and aggressive sound design conspired to greatly distort voices and instruments. What did work, however, were the electronic outer space effects, including chopper noise that had me looking around for annoying helicopters.

The main problem, though, was that Royce Vavrek’s libretto, sentimentally anthropomorphizing outer space, seemed to send Prestini astray. There was little here on the level of her exquisite earlier opera, “Oceanic Verses.” Even Eliza McNitt’s VR film, “Fistful of Stars,” proved anti-climactic. Climatic music receded into the background as we fiddled with phones and low-end viewers (blurry for glasses wearers).

In the end what may be the most operatic about “The Hubble Cantata” is not the soap opera attempt to dramatize the universe but just the opposite, the work’s ability to evoke the sheer vastness of what lies beyond our experience. That really is a promising new world for opera.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.