Review: Helen Molesworth’s final show at MOCA is the anti-celebrity show we need right now

- Share via

Persuasive group exhibitions of contemporary art are just about the toughest kind for a museum to successfully pull off. That’s one reason that the thoroughly engaging “One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art,” newly opened downtown at the Museum of Contemporary Art, is so special.

Another is that it’s exactly the kind of exhibition we need right now.

In our often soulless, lopsided celebrity culture, it’s an anti-celebrity show — iconoclasm for an age swamped by icon worship. “One Day” celebrates the virtues of the quotidian, the curious and the eccentric. And it is built around a superlative exemplar of those irreverent qualities.

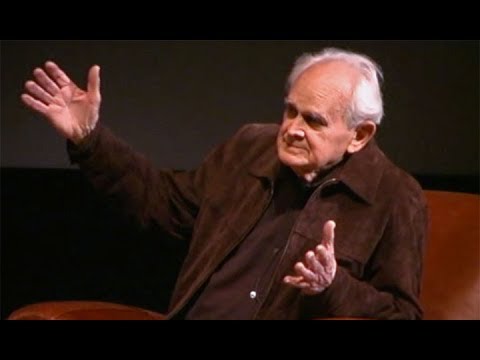

I think of Manny Farber (1917-2008) as a painter who wrote movie criticism on the side. His paintings and his criticism are both marvelous. Yet, the writing has had the broader cultural impact.

One obvious reason is that movies have far bigger audiences than paintings do — especially paintings made in San Diego, where Farber lived, worked and taught (at UCSD) starting in 1970. He was born in Arizona, went to school at Berkeley and Stanford, and lived in New York in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s. Farber’s movie criticism — published in the New Republic, the Nation and elsewhere — is revered for its punchy style, close observation, openness to the overlooked and, not least, its wit.

“One Day” is a monographic show interwoven with a group exhibition. The former consists of the still life paintings Farber started making in the mid-1970s. The latter represents 36 artists who were not necessarily influenced by him but whose work shares a sensibility or displays a certain affinity with elements of those paintings.

The merger is about framing a way of thinking visually. That’s a tough thing to execute, but it is beautifully accomplished.

The show opens with several of Farber’s so-called “candy,” “auteur” and “stationery” drawings — tabletop still lifes in oil, ink and pastel on paper. Hershey bars, Red Hots, notebooks, writing implements and other objects are scattered across the sheets.

These items are related to movies, specifically to the theater’s concession stand and the critic’s tools. The still lifes focus on mundane but vital things that exist around the unseen main event — what’s up there on the silver screen.

This is termite art.

Farber gave the quirky name to unpretentious, unfashionable and virtuoso art that burrows in deep, avoiding grandiosity and ostentation. (The critic called that white-elephant art.) The vantage point on the still life paintings is from above, a bird’s-eye view that puts the artist in the director’s chair. The tabletop fills the page, edge-to-edge, the way a movie fills the screen.

That formal point of view is highly unusual for a still life, more commonly seen from the side and framed as a fragment carved from (or arranged within) a larger context. Farber makes his into a complete universe. He sustained this POV for the next 30 years.

Fourteen Farber still life paintings are in the first room. (Twenty-three are in the show.) The second room arrives with a Big Bang.

“An End to Modernity” is a spectacular sculpture-as-chandelier by Josiah McElheny, the wizard of hand-blown glass. The ellipsoidal shape, roughly 15 feet across and suspended from the ceiling, is composed of 230 chrome-plated aluminum rods poking out from a mirrored sphere, about a third of them tipped with electric lights. Hanging at eye level, the 700-pound sculpture of polished metal and twinkle lights is like a birthday party sparkler.

The explosive configuration is based on complex scientific models of quasars, galaxies and the creation of the universe. But it takes the exquisite form of a decorative hanging lamp joyously made with an obsolete artistic technique and frivolous materials. Calling the work “an end to modernity” might be an understatement.

It is also a paradox: Liberating art from academic formula was one of modernity’s ends.

Across the way, a casual but judiciously brushed painting by Patricia Patterson, Farber’s widow, shows a life-size woman in a kitchen stirring a pot on the stove. Anonymous, she’s seen from behind. Yet the asymmetrical design of delicate white flowers strewn on her cerulean blue dress is like stars dotting a night sky.

Visually, the dress echoes the radiating pattern of seed-like shapes gouged from a thick paste of oil, acrylic and sand in Jennifer Guidi’s small abstract painting, “Pink Sky Mountain,” also in the room. Time’s passage, implied in all three of these works, is quietly pictured in Dike Blair’s small gouache of a pair of alarm clocks — one black, one white — each telling a different hour and minute. The clocks are multiplied by tabletop reflections.

Presiding over all of these works, made by artists of wildly different temperaments, achievement and renown, is a gorgeous Farber still life. “About Face” is a horizontal panel, just 21 inches high but 6 feet wide. The odd shape invokes landscape.

Against a screaming yellow ground, bits of green and crimson underpainting showing through, two gangly sunflowers rise up on cut stalks from blue pitchers. One flower is shown from the front and the other from the back, as the title implies. A humble plate of figs and an eggplant lie nearby. The tall sunflowers, punching up from the tabletop far below, create a vertiginous space.

The dominant shapes in the composition are oval and curvilinear, which keep your eye traveling around the length and breadth of the pictorial landscape. Farber paints still lifes that are anything but still — an artifact of his love of motion pictures, no doubt. Sunflowers show some Van Gogh love too — termite-style, the only way to acknowledge a genius predecessor without looking absurd.

The way in which this enthralling gallery has been installed is repeated again and again throughout the show. Disparate works of art one might not otherwise imagine cohabiting nonetheless chatter away with one another, like stimulating guests at a party.

Near the final room, a modest floral motif decorating a seemingly insignificant bathroom wastebasket in a Becky Suss painting gets picked up and inflated into a cabaret floorshow by an actual bouquet of exotic flowers on a pedestal by Maurice Harris, a sculptor turned florist. (He’ll refresh the arrangement weekly during the show’s run.) Then, a poignant circle closes in a Jordan Casteel painting of a funeral arrangement discarded next to a trash can on an urban street.

Suss works in Philadelphia, Harris in Sacramento and Casteel in New York City. All three are under 38 and are new to me.

“One Day at a Time” is full and fertile, a conversation among talented artists and a sympathetic curator who all know what they’re about. The swansong of Helen Molesworth, MOCA’s extravagantly talented former chief curator, this is a show that artists will surely love, and a general public might too. It’s user-friendly yet enjoyably strange.

It’s also a show that other curators and museum folks would benefit from seeing. There are lessons quietly waiting to be absorbed, in a demonstrable rather than sermonizing way.

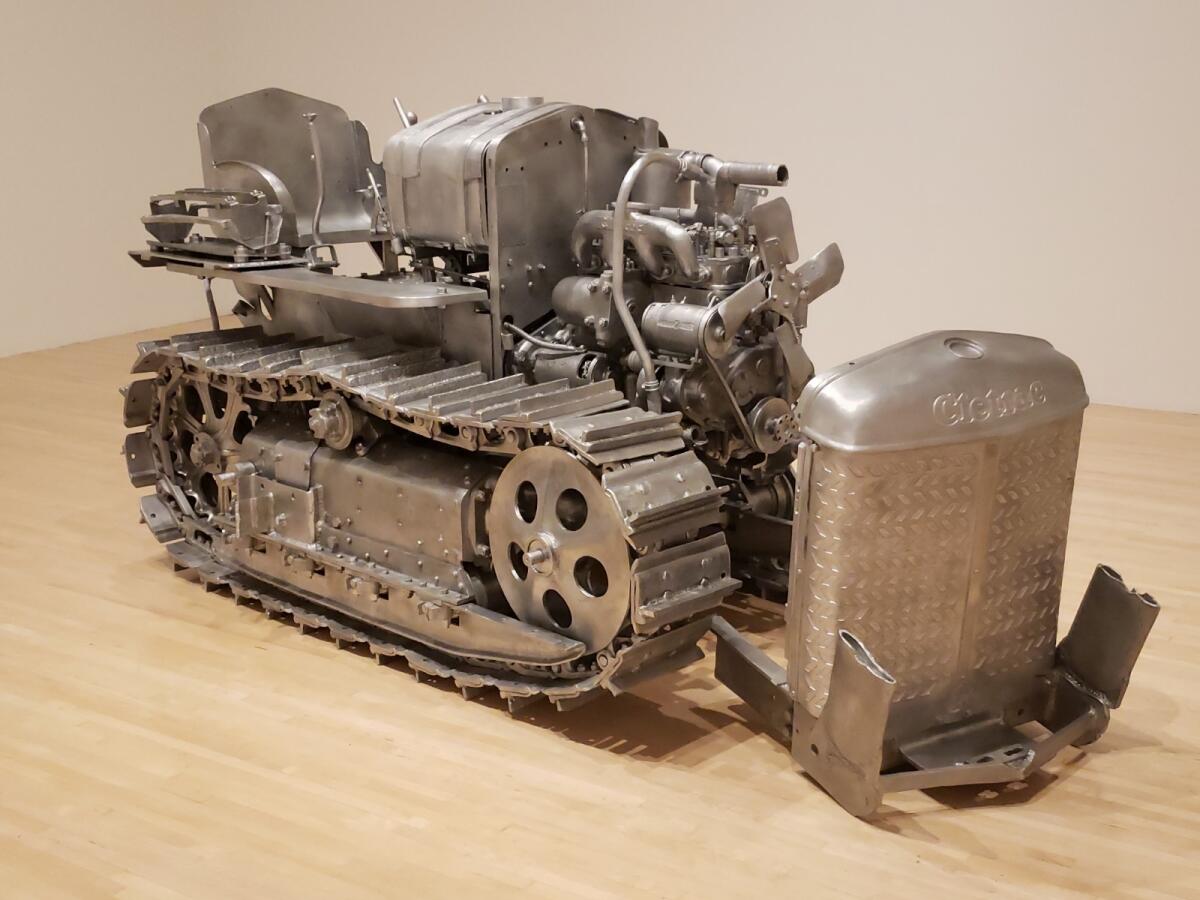

Now more than ever, art museums are afflicted by pressure to follow the marketplace and shepherd celebrity white elephants. A savvy institutional critique is accomplished by putting Farber’s termite art front and center, then surrounding it with diverse works by appealing newcomers like Casteel, midcareer wonders like McElheny and established superstars like Charles Ray. (His ruined life-size tractor, entirely handmade from cast-aluminum parts, down to the nuts and bolts, must be seen to be believed.)

Sometimes I think that the more people feel like nobodies, the bigger the celebrity balloon gets. It’s a gassy compensation — vaporous and finally unproductive. “One Day at a Time” goes another way. It’s a rousing celebration of the termites, which for the time being have chased the white elephants away.

MOCA, 250 S. Grand Ave., (213) 621-2766, through March 11. Closed Tuesday. www.moca.org

christopher.knight@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.