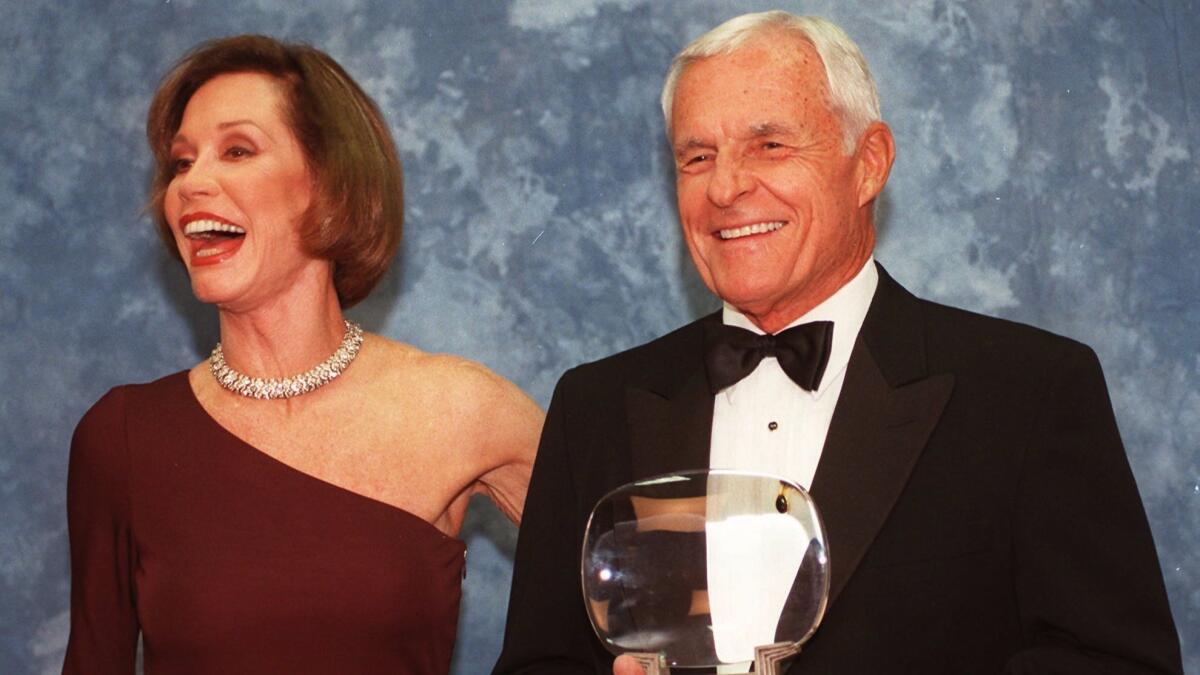

Appreciation: TV executive Grant Tinker gave us smart shows like ‘Mary Tyler Moore’ and ‘Hill Street Blues’ by putting the best ideas first

- Share via

Television is a collaborative art, the work not just of writers, producers, directors and actors, but also of people who make decisions about what you will see and what you won’t. As an art, it’s also a business, and as a business, also a game, half-chance, half-skill — you have to know when to fold them, and when to hold them. Some people have a knack for playing it, and none more than Grant Tinker, legendary independent producer, programming executive and NBC chief executive, who died Monday at the age of 90.

Tinker, whose career began in radio, was a television man most of his working life; even his years in advertising, at McCann Erickson and Benton & Bowles — on a late-1950s, early-1960s break from NBC -- were as a developer of television properties, at a time when networks sold air time to sponsors, who supplied them with shows.

But he knew the business from more than one side – as a network executive he knew what it was to be a creator, and as a creator, he was intimately familiar with the executive mind set.

Before and after stints in network programming, he co-founded MTM Enterprises with then-wife Mary Tyler Moore; during Tinker’s tenure, the production company became synonymous with smart television in the 1970s, with shows including “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and its fine spinoffs (“Phyllis,” “Rhoda,” “Lou Grant”) as well as “The White Shadow” “WKRP in Cincinnati,” “The Bob Newhart Show” and “Hill Street Blues.”

He sold his shares in the company when he left in 1981 to take over an ailing NBC, whose fortunes he would reverse with series such as “St. Elsewhere,” “The Golden Girls” and “The Cosby Show,” in order to avoid a conflict of interest. A quaint thought nowadays.

This range of experience, along with what has been remembered by many as a naturally generous spirit, made Tinker famously protective of his writers and producers, and allowed him a degree of mental freedom in a business – big-league network television – famously averse to risk.

In a 1998 interview with the Television Academy, he called MTM a “boutique” company. “There was nothing we had to do because we had thousands of people on the payroll. We just did the things that appealed to us, some of which didn’t appeal to others, so they became failed pilots or whatever.”

With some exceptions, Tinker wrote in his 1994 memoir, “Tinker in Television: From General Sarnoff to General Electric,” “new series need time to find an audience. And the more they vary from the tried and true, the more time they need. The art of programming is in making the correct judgment about what, if anything, can and should be done to help them succeed.”

At NBC, slow starters like “Cheers” and “Hill Street Blues” were given time to find their audience, or be found by them. And it’s worth noting that when “Mary Tyler Moore” premiered in 1970, as a multi-camera comedy shot before a live audience, it was an unusual move – single-camera sitcoms (with laugh tracks) like “That Girl” and “Bewitched” were the order of a day. But it was a form that Tinker found “natural and indigenous” to the medium. When Norman Lear’s “All in the Family” quickly followed, the new style for quality, thoughtful TV comedy was set.

Tinker’s famous dictum “First be best, then be first,” which, in his memorial season has been much quoted, came from a speech he made to NBC affiliates when the network was still “in shambles and morale was down the tubes” and even Tinker himself thought its chances were slim.

He said it, he later explained, “because I wanted to get off on a hopeful note, not because I thought it was going to come true.”

But hope, as Tinker’s career showed again and again, is where good things begin.

robert.lloyd@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.