Video game music comes to the orchestra concert hall

- Share via

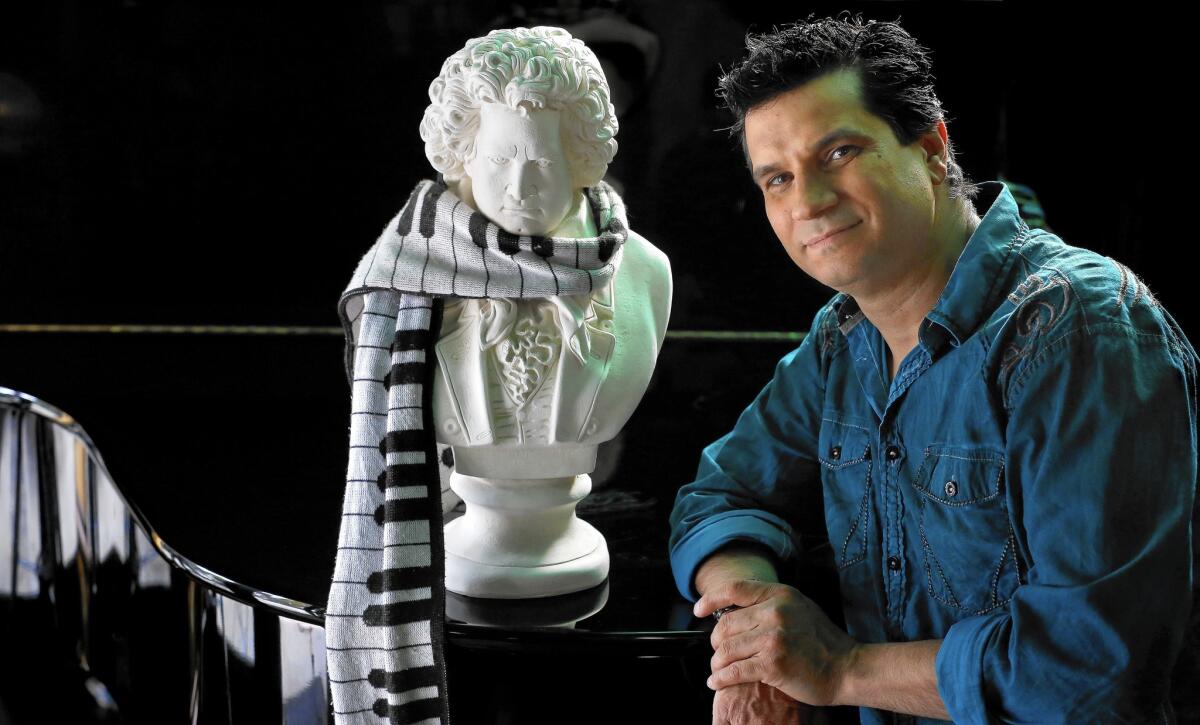

He’s an impresario with a little-boy streak. He plays a guitar shaped like a sniper rifle, keeps pirates by the pool and is one of the world’s leading composers of video game music. He can rhapsodize for long stretches about Bugs Bunny, Spider-Man, Rocky Balboa and Beethoven, whose bust, draped in a scarf, looks over a piano in his home in the hills of San Juan Capistrano.

“If Beethoven were around today he’d be a video game composer,” said Tommy Tallarico, who has worked on more than 300 titles, including “Mortal Kombat” and “Knockout Kings,” that have about $4 billion in sales. “Video game music is the most unique in history. When you play a video game, that character is you. His music is the soundtrack of your life.”

Music’s power to evoke warriors and imaginary galaxies struck him as a boy when he saw “Star Wars” in a theater in Springfield, Mass. The soundtrack by John Williams was mesmerizing. “I said, ‘Who is this guy?’ I read about him and how he was influenced by these Mozart and Beethoven guys. I checked out a copy of Beethoven’s greatest hits from the library and it changed my life. I sat down with Symphony No. 9 and tore apart every note.”

Tallarico, who has no formal musical training, has spent the last decade bringing two contrasting worlds together. His “Video Games Live” concerts have reportedly sold more than 1 million tickets and been performed by symphonies in the U.S., Europe, China and the Middle East. Orchestras, including the San Francisco Symphony, have sold out concert halls to gamers, mostly young men who spend countless hours traversing fantasy-scapes and virtual battlefields.

“Folks come up to me after the shows and say, ‘Tommy, when are you coming back?’”

A swift man with a sly laugh, Tallarico, a cousin of Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, adds a bit of carnival flash to the often staid classical scene. Struggling with fewer subscribers, shrinking donations and questions of how to compete with on-demand entertainment, many orchestras have been experimenting with innovative programming even as purists fret that classical music is straying from tradition to appease trends and fashions.

“We’re trying to find the sweet spot that transcends generational differences,” said Susan Webb, marketing director for the Oklahoma City Philharmonic, which last month performed a “Video Games Live” show in which audience members dressed up as their favorite characters. “We love our musicians in their tuxedos, but this takes it to a whole new level in reaching out to younger, tech-savvy audiences.”

Gamers and Tchaikovsky

Orchestras these days can no longer rely on the likes of Brahms and Mahler to fill seats. At the same time, video game music has become increasingly sophisticated. The bleep-bleep, blip-blip days of “Pac-Man” and “Space Invaders” are, like the Cold War and Woodstock, ancient history. Scores for “World of Warcraft” and other games call for strings, woodwinds, brass and choruses — whirling scales for an industry whose franchises rival Hollywood’s.

“It’s not the solution to the underlying problems of orchestras, but it’s a way to reach out to an audience not usually associated with classical music,” said Emmanuel Fratianni, a Los Angeles-based classically trained pianist who conducts and composes video game music. “It’s impressive and intimidating for gamers to step into this [concert] world. But will they come back for a Beethoven or Mozart? That’s our goal. We need to blur the lines a little more to expose the gamer to Tchaikovsky.”

Classical music, including Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” and Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata,” has been featured in video games for years. In 2011, the London Philharmonic Orchestra released “The Greatest Video Game Music,” which Rolling Stone called the year’s “weirdest hit album.” The CD included music from “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2” and “Angry Birds” and was followed with a sequel.

“I find it heartening that gamers have found classical music,” Martha Gilmer, chief executive of the San Diego Symphony, which performed “Video Games Live” last year. Merging classical music with pop culture is reminiscent of early 20th century cartoons, notably Walt’s Disney’s “Fantasia,” which featured music by Bach, Schubert and Stravinsky.

Gilmer added that like the classical masters, the best video game composers understand melodic lines and the varied colors and textures of clarinets, flutes and other instruments. Played by a full orchestra, today’s video game music, she said, takes on an “epic proportion” that could inspire gamers to return to the concert hall. “Live music has great impact,” she said.

But Tallarico, 47, who grew up listening to Jerry Lee Lewis, believes many orchestras view the world through antique lenses. He composes his scores with computer software, and his concerts are kaleidoscopes of rising mists, extraterrestrials, warriors, heroes, spacecraft careening through solar systems, all to thrumming cellos, heralding French horns and spiraling flutes. Audiences stand and cheer.

“These orchestras need to hire me to produce a Beethoven concert,” said Tallarico, who debuted “Video Games Live” in 2005 at the Hollywood Bowl with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. “I love Beethoven, but I have a problem sitting through two hours of Beethoven. It’s a bunch of people on stage in tuxedos going ‘ssshhh.’ I want everyone to clap and scream when they want.”

Many musicians might wince at that notion. Video game music, after all, is a sideshow. But with dystopian landscapes, cinematic crispness and good-versus-evil narratives, game music summons worlds that speak to the fears and ambitions of an age that is at once entranced and intimidated by technology. Unlike most movies, where music is layered in after filming, music in the best video game feels ingrained in the plot.

Among the most accomplished is the score from “Final Fantasy,” composed by Nobuo Uematsu, whose youthful piano playing was inspired by Elton John. Like “Video Games Live,” Uematsu’s scores are performed by orchestras around the world in a program called “Distant Worlds.” Another popular touring show is the music from Nintendo’s “The Legend of Zelda,” much of it written by Koji Kondo.

TV, film experience

Like a number of video game composers, some of whom can earn more than $500,000 a year, Fratianni came to the industry after working on music for films and TV shows, including “Breaking Bad.” In 2005, Tallarico, Fratianni, Michael Plowman and Laurie Robinson composed the game music to “Advent Rising.” The score was inspired by Italian opera and recorded with a 70-piece orchestra on a Paramount soundstage. The choral passages were sung by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

A review by the website, Video Game Music Online, praised the compositions for “lush orchestration, underlied by romantic piano work” and tracks that “re-inforce the atmosphere and mood of the game.”

Tallarico is a master at creating atmosphere, ever since he was a Massachusetts boy banging on the family piano or playing “Space Invaders” deep into the night. After driving across country in 1990, he said, he lived briefly under a pier in Huntington Beach and took a $4.25 an-hour job selling guitars in Santa Ana. He found a second job testing video games for what would become Virgin Interactive. “There was no such thing as a video game composer back then,” he said, adding that he started working with programmers to code music into games.

The Internet and fast-evolving graphics technology turned the industry into a global force. The music matured as well. “I could write a three-minute piece about 100 men with swords coming on horseback to a village,” he said. “It’s epic music. Violins going, timpanis going crazy, men, women and children’s choirs going. I can take it and record it in a bunch of different ways with different intensities.”

His home in San Juan Capistrano looks as if a 12-year-old with a huge bank account went wild. It includes a life-size Indiana Jones, a Spider-Man room streaked with real spider webs, a Disney room with an original drawing of Pinocchio, a framed celluloid still from a vintage 1940s Bugs Bunny cartoon, a clutch of full-size “Star Wars” characters and, by the pool, a statue of Merlin lurking near a lawn tiger bought in Las Vegas.

“These are all the things I grew up with,” he said. “I’m making a Willy Wonka section right now.”

He is surrounded by childhood images. Pictures of his grandparents, immigrants from Italy, hang in the stairway. His father, who once sold life insurance, is his chief financial officer and his brother handles merchandising. “Yeah,” said Tallarico, whose bar is filled not with liquor but with dozens of bottles of balsamic vinegar, “in typical Italian fashion I moved my family out here.”

Downstairs near a room that resembles the inner chamber of an Egyptian pyramid sits an artifact: his clunky 1975 Telstar video game console. He still plays it. He said before the first “Video Games Live” concert many people told him it would flop: Gamers don’t go to see orchestras and the evening gown set doesn’t play “Grand Theft Auto” and “Final Fantasy.”

Tallarico these days hosts many “Video Games Live” shows, playing guitar and flitting through laser lights in front of the orchestra. Some classical musicians remain skeptical.

“I can tell right away who the problems will be,” said Tallarico. “Some of the older musicians have been playing the masters for 40 years and now we come along with our video screens and fog machines and they look at the music score and say, ‘Who is Sonic the Hedgehog?’ They kind of snicker, but when they play the music they say, ‘Hey, this sounds like Carmina Burana by Orff.’”

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.