Teller talks up his directorial projects ‘Play Dead,’ ‘Tim’s Vermeer’

- Share via

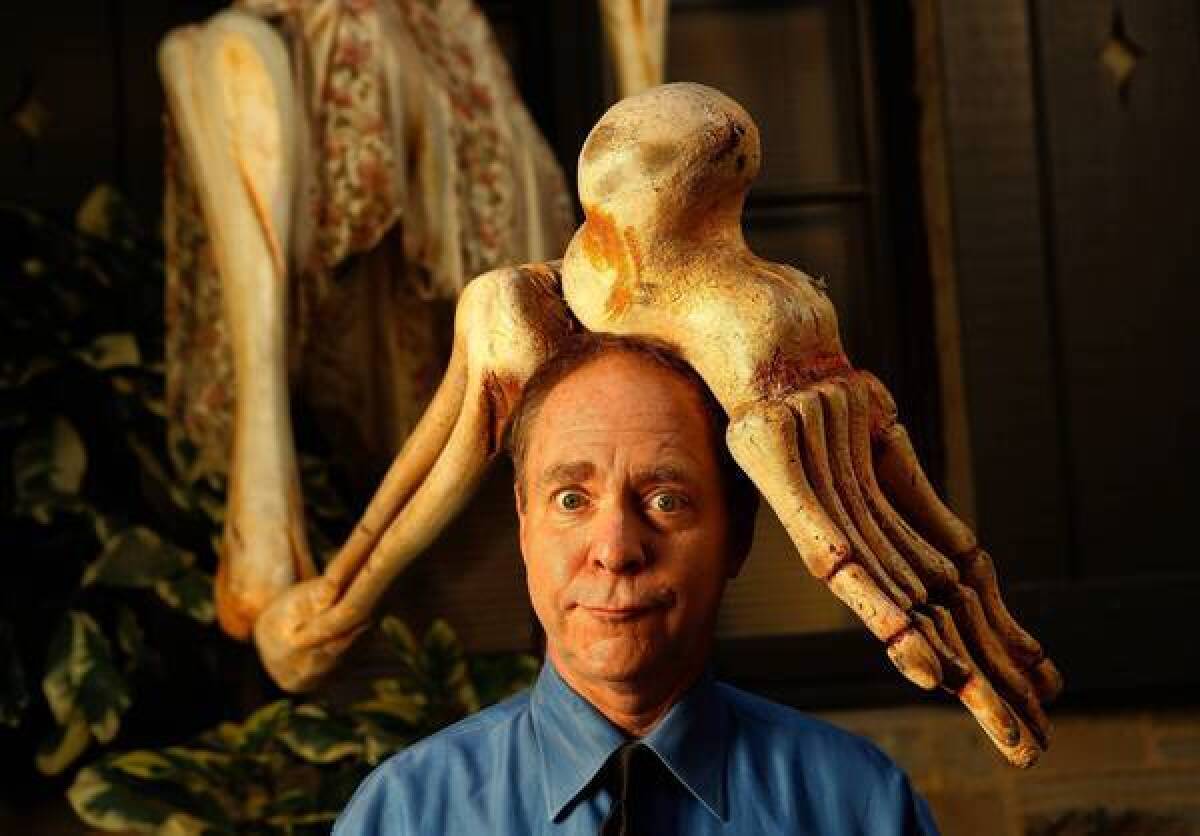

Teller, the usually silent half of the renegade magician duo, Penn & Teller, recently perched on a couch at the Geffen Playhouse, where he had a lot to say about two projects he has helmed as director — “Play Dead,” magician Todd Robbins’ one-man creep show, which runs through Dec. 22 at the Geffen’s Skirball Theater, and “Tim’s Vermeer,” about inventor Tim Jenison’s quest to unearth the Dutch painter’s techniques and re-create his work in a Texas warehouse. The film was executive produced by Penn Jillette, who also appears in it, and opens Dec. 13.

What were the spook shows of the 1930s and ‘40s that inspired “Play Dead”?

As more live theaters were turned into movie theaters, magicians had no place to work. And so a crazy magician decided he’d make this business proposition to movie-theater owners: On Saturday night at midnight, I’ll do a magic show that’s really spooky and I’ll do sections in total dark, so all the teenagers who want an excuse to grope each other will have this opportunity. It was a great date thing that made millions of dollars for people up until the early 1960s around the country.

CHEAT SHEET: Fall arts preview 2013

Both Todd and I have a great affection for the idea of that form, a piece of theater that reaches out and touches you. And we both also have a great fascination for the history of the way spiritualists duped their clients. There is no such thing to my knowledge as communication with the dead. However, there has been some fabulous trickery involved in creating the impression of the dead returning. And it’s wonderfully entertaining and thrilling and, as long as you don’t believe that it’s happening for real, a perfectly happy moral endeavor in the theater.

FOR THE RECORD:

Sunday Conversation: The Sunday Conversation feature in the Calendar section said Penn Jillette executive produced the film “Tim’s Vermeer.” Jillette produced the film.

How do you scare sophisticated audiences in 2013?

Remember that it’s a scare that’s voluntary. They’re coming in fully in the mood to shriek and laugh and grab the person next to them. And one of the first things we do in the show is turn out the lights. When you leave people in the dark, they misbehave a little bit and they start to scare each other. The first thing we do is unleash what’s inside them with the power of darkness.

Todd tells you true stories about mostly pretty unpleasant people. And these true stories have a way of creeping under your skin. And then periodically he does some nerve-wracking things. He tempts people to get involved. Incidentally, there are no stooges in this show. It’s a matter of letting everybody know this is a big joyful game, and then they let down their guard and enjoy having their guard invaded.

Why do you think death is such a compelling subject for entertainment?

In real life, death is no fun at all. But to go to a theater where you can look death in the eye and laugh and come out alive is very exhilarating. It’s empowering.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Incidentally, there are tricks in this show that have fooled some of the best magicians in the world.

Let’s talk about “Tim’s Vermeer.” How did the film come about?

Penn had for a long time known Tim Jenison, who’s the pioneer of desktop video. One of his daughters had given him a copy of David Hockney’s book “Secret Knowledge.” Hockney said right about the time that art stops looking like that stiff medieval stuff and starts looking like photographs, let’s look at what’s going on in technology at the same time — and there’s substantial evidence that artists were using lenses and mirrors probably in secret, because it was an industrial secret, to get extremely accurate drawings onto their canvases.

Tim always thought that Vermeer has a particular photographic quality to it, so he began to think about the missing link between Hockney’s work and Vermeer. And the answer is, if you are able to project an image using something like the camera obscura, if you’re an artist you can trace around the shapes but there’s really no way to match up the brightness and color with the color of your paint. And Tim suddenly pictured a very simple thing: a 45-degree angle mirror placed between a subject and a canvas that are at right angles and he pictured the possibility of matching the color exactly at the edge of that mirror. The heart of the film is about how he’s unstoppable in his attempt to become Vermeer.

When Penn called him and said, “Can you come and talk to me about something other than show business?” Tim flew in and said, “I’m thinking of reproducing Vermeer’s studio in my warehouse in Texas to see if my idea really works.”

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

Did he fund it himself?

Yes. Penn said we’re going to document everything. Nobody would fund it. One, because it sounded like it might be a dull academic experiment, another it sounded a little crackpot and third, Penn is involved. And Penn is half of Penn & Teller and we are famous for lying. So I think they may have thought it was a Borat-type prank. So Penn and Tim said “we’ll fund it ourselves.” And Penn knew that I’ve directed the Penn & Teller stuff for a long, long time, and the fact that both my parents were painters and the fact that Tim’s method, this 45-degree-angle mirror, is one of the major principles used in magic onstage. He thought I was the one person who would understand it but maybe go after it in a different way.

One issue raised in the film is whether artwork using optical devices can be considered authentic. What do you think about that?

Of course it can. The idea of art is to take something that’s in your heart and get it into somebody else’s heart by whatever means you use. Making something beautiful is the point. Why would there be rules about that?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.