Review: ‘Regarding Susan Sontag’ looks at a rock star of intellectuals

- Share via

“I love being alive” — these are the first words Susan Sontag speaks in “Regarding Susan Sontag,” Nancy Kates’ documentary on the late American novelist, critic and ponderer of culture high, low and whatever.

For all that she was as a professional deep thinker, her life was a paean to liveliness. The oft-quoted dictum that ends her 1964 essay-manifesto “Against Interpretation” — “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art” — translates broadly as “think less, feel more.” At the same time, with her breakthrough “Notes on ‘Camp,’” she helped tear down the barrier between so-called high art and low, making what was once dismissed as trash — Busby Berkeley movies, sci-fi films, pornography — subjects for serious aesthetic study.

Premiering Monday on HBO, “Sontag” is a kind of mash note in the form of a biography. This is, of course, true of most such films — you need to love your subject enough to spend the time and money a project like this demands — and Kates (“Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin”) is not blind to Sontag’s sometimes difficult personality, her self-contradictions, her self-involvement, her self-doubt. (“She was never able to know what goes on inside another person,” friend and sometime lover Eva Kollisch says here. “Susan was not sensitive.”)

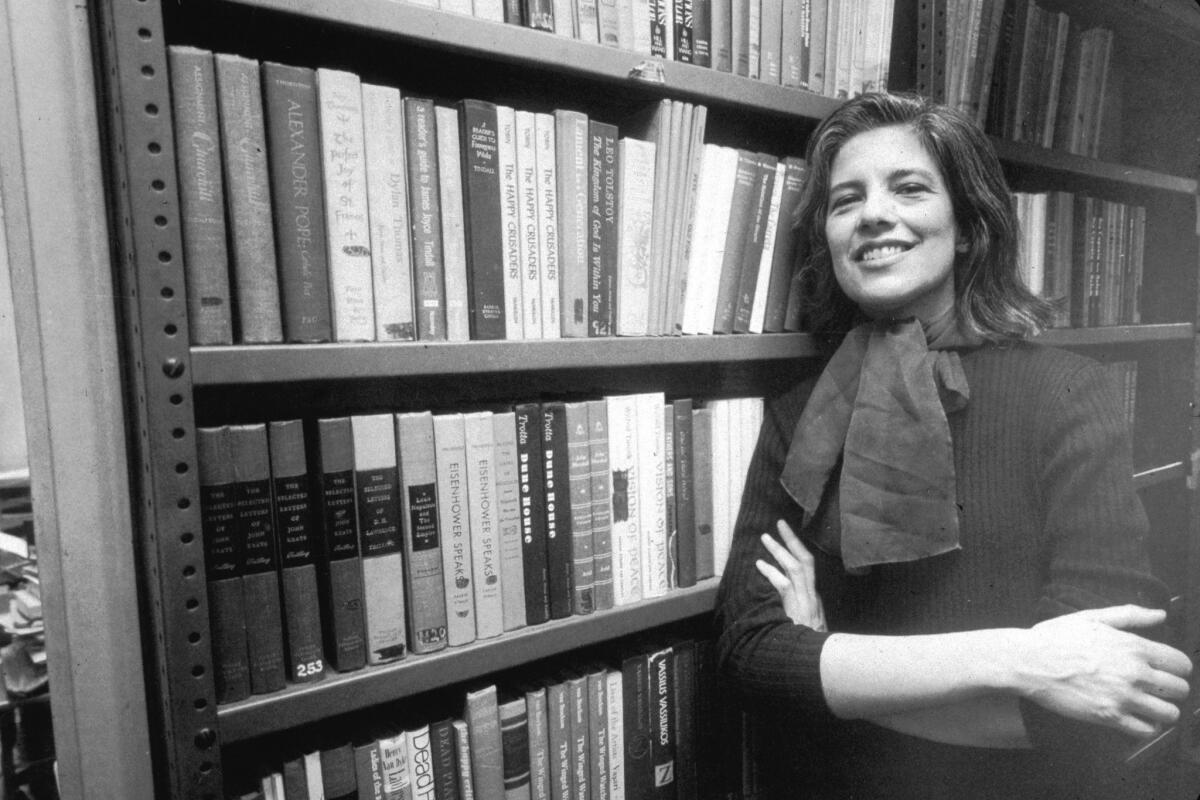

In the case of Sontag — who died in 2004 at age 71, of a form of leukemia, having outlived her first terminal cancer diagnosis by 30 years — the persona is part of the package: Among American intellectuals, she was the rare rock star, and though her work stands on its own with allowance made for any writer’s ups and downs, her personal magnetism is very much part of the story; she was a thinking person’s pinup, friendly and formidable, impish and intense, bright-eyed, wide-smiled, with a head of hair that amounted almost to a signature. Although the author of “On Photography” claimed to be “hopelessly amateur” in front of a camera, the camera says otherwise. (Her last and longest relationship was with photographer Annie Leibovitz.)

This alone makes for a highly watchable film, though Kates also dresses the screen with poetical visual interludes — animated type resolving into a portrait of the writer, a naked female torso to accompany Sontag’s sexual realizing that she liked women in a way she hadn’t liked men. (It wasn’t until 2000 that she publicly acknowledged her bisexuality.) These moves are not strictly necessary, but they give the film a dreaminess that suits the subject and complements the grainier, rougher archival footage.

Writing was her organizing and motivating principle — starting to write, as a child, was “like enlisting in an army of saints.” Her stepfather, whose name changed her from Susan Rosenblatt to Sontag, told her that she shouldn’t read so much or else she’d never get married. “It never occurred to me that I would want to marry someone who didn’t like someone who read a lot of books.”

But to think is necessarily to be contrary, to take stands even against one’s own positions to test, and if necessary to change them: “I like that adversary position,” Sontag says here (Patricia Clarkson steps in as the voice of her writing). Her contrariness ran back to North Hollywood High, in whose student paper she wrote, “The battle for peace will never be won by calling anyone whom we don’t like a Communist”; in regard to the Vietnam War, she would later claim, “The white race is the cancer of human history”; and again, after Sept. 11, asking, “Where is the acknowledgment that this was not a ‘cowardly attack’ on ‘civilization’ or ‘liberty’ but an attack on the world’s self-proclaimed superpower?” She was never out to win friends.

To say, as Sontag does in “Notes on ‘Camp,’” that “the two pioneering forces of modern sensibility are Jewish moral seriousness and homosexual aestheticism and irony” may not be defensible from every angle, given all that it leaves out, but it has the feeling of being something useful, a frame, something to play with or respond to. (Her titles alone — “Illness as Metaphor,” which advised against it, and “Styles of Radical Will” and “Regarding the Pain of Others” — can get you thinking.) Sontag’s best writing gives one permission to see things in a new way — or makes it impossible to continue to see them in the old one.

------------

‘Regarding Susan Sontag’

Where: HBO

When: 9 p.m. Monday

Rating: Not rated

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.