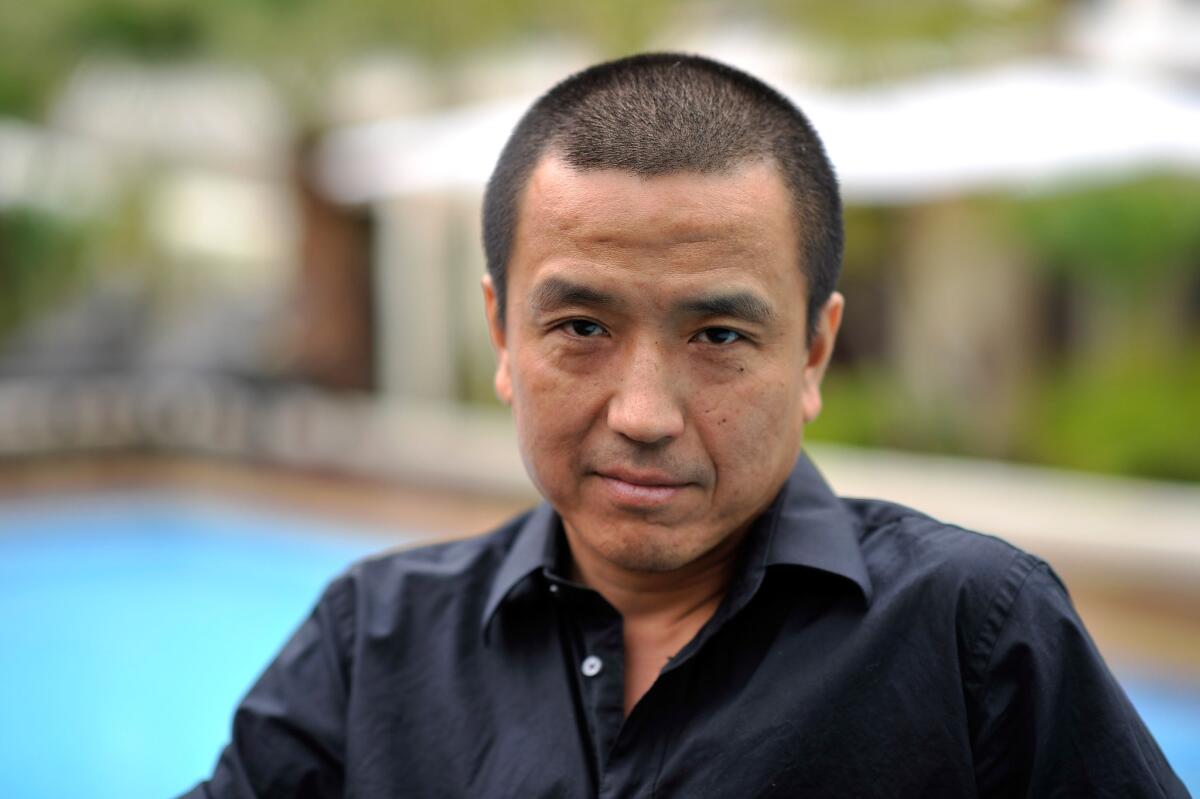

‘Blind Massage’ director Lou Ye talks of film challenges, China market

- Share via

Reporting from BEIJING — Mainland China director Lou Ye’s “Blind Massage” was one of the big winners at the 2014 Golden Horse cinema awards in Taiwan, the Chinese-speaking film world’s equivalent of the Oscars. His film took home six prizes, including best feature film at the November event.

But the movie about a group of blind masseurs’ lives and tales has yet to be seen widely — either inside or outside China. “Blind Massage,” which opened in mainland theaters in November, has made only $2 million on its home turf. Aside from a few overseas festivals, including Berlin and the New York Asian Film Festival, it has otherwise not traveled far. It won’t even be shown in Taiwan until Feb 19.

Lou focuses on emotions and romances placed in rather edgy settings of contemporary urban China. During the early stage of his career, his strong personal style attracted international attention when his neo-noir “Suzhou River,” about a man obsessed with finding his ex-lover, received the Grand Prix at the Paris Film Festival in 2000.

Regarded as fearless and innovative by his admirers, Lou is not one to shy from violence, sex, erotic longings, homosexuality, adultery, revenge or jealousy. Aesthetically, he often favors blurry images and jump cuts.

His fourth film, “Summer Palace,” was screened at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival without permission from Chinese authorities. The government-run Film Bureau prohibited the movie’s release in China, with authorities describing the sound and picture quality as poor. But the film’s full-frontal nudity and political undertones of the Tiananmen Square protest in 1989 were widely understood to be the real reasons the film was barred — and why Lou and the producer were banned from releasing any films in China for five years.

Lou, though, didn’t stop. He made two films during the ban. Both movies premiered at European film festivals, and many of his works have been Chinese-French co-productions.

“Blind Massage” centers on a group of blind masseurs in a massage parlor in China. Lou refuses to let audiences view the disabled people as saints; the blind and the sighted, he suggests, have to struggle equally in the dark world of desire, love and wealth. The sometimes out-of-focus images and constant changes of location are Lou’s attempt to portray the world of the blind and help viewers rely on all their senses to feel, instead of merely see, the world.

Nicole Liu in The Times’ Beijing bureau caught up with Lou recently to discuss the film:

What were your biggest challenges making “Blind Massage”?

I realized I needed to shoot a visual story of people who cannot see.

From the title of the film, audiences might expect to see a group of gentle people engaged in a very quiet profession. But quite surprisingly, this film has multiple scenes of violence. Was it your intention to create a shocking effect?

Viewers can interpret those scenes however they want. Being blind doesn’t mean one cannot see. This film is made for those people who have the capability to see.

Your signature “blurry” visual techniques help to convey the unique and real world of the blind. However, such techniques might be used against you; for example, authorities previously used the excuse of “poor quality of sound and images” to ban you.

Ironically, viewers really cannot see and hear clearly this time in “Blind Massage,” yet the film’s submission to censors and the authority’s approval went smoothly — which just proved that the so-called censorship on the basis of technology [for “Summer Palace”] was just part of the censorship of ideology; it was just an excuse.

Your producer says you made over 100 different edited versions of “Blind Massage” — is that typical for you, and why so many? Was this in response to censorship issues, and were you instructed to shorten or remove any graphic scenes?

It is normal; all my films go through a long period of editing. It is just the way I work, it’s not at all for censorship.

Very few scenes were cut [in China]: One was the few seconds when the main character’s neck is splashing blood after it is cut open. Very few of the two couples’ sex scenes were reduced and edited.

“Blind Massage” played only on 3% of the screens in China and made only $2 million, even though you’ve signed contracts with several cinemas to incentivize them to extend the period of screening. Why did this movie have such limited exposure although it won many prizes overseas?

Normally, a director’s job doesn’t include distribution, promotion, screening and box office. There is no direct relation between them and the awards the film receives. A director’s creation of film should not be affected by [thinking about] how many cinemas will screen it.

What is the market for artistic films in China today? Some cinema owners say audiences don’t like these films so they don’t play them. Some film buffs say the reason these films aren’t more widely accepted is that cinema owners refuse to play them. Where do you think the problem is?

In general, the artistic film market in China isn’t very good. And I think it is normal. On one hand, the market fluctuates, on the other hand, Chinese cinema owners are not capable of making profit from artistic films; they still don’t know how to run the artistic film business. It seems audiences understand the film business better than most of the people who run the cinemas.

What did you do during the five-year ban? How has the ban changed you?

I finished two films, one was “Spring Fever,” shot using a home digital video camcorder, and another one was my first English-language film, “Love and Bruises.” The five-year ban made me more free. And I’m happy to shoot films back in China.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.