Q&A: Beijing film festival: Marco Mueller back where his love of film began

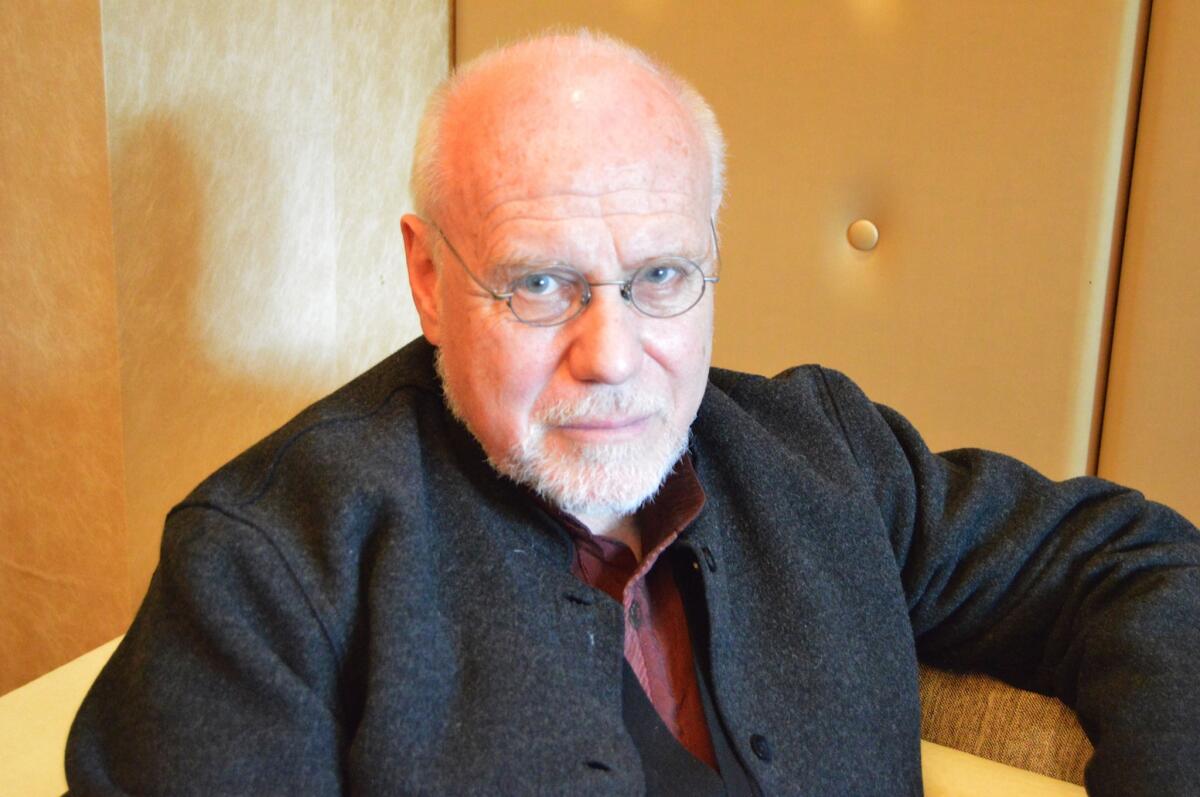

Marco Mueller, former head of the Venice and Rome film festivals, is special advisor to the Beijing festival this year.

- Share via

Reporting from Beijing — Marco Mueller, the former director of the Rotterdam, Locarno, Venice and Rome film festivals, is serving as a special advisor to the Beijing International Film Festival this year, programming the competition slate. The fifth annual event starts Thursday.

For Mueller, whose love of cinema began in China in the 1970s, the assignment is a homecoming of sorts. The 61-year-old grew up in Rome speaking French, German, Italian and Portuguese. He started studying Chinese at 14 and came to Beijing as a graduate student in late 1974, two years before the end of the Cultural Revolution, a period of mass upheaval and disruption, particularly at educational institutions.

We caught up with him in Beijing on the eve of the festival to discuss his return to China, his unusual experience as a student studying in the country during the final days of Mao Tse-tung, and the future of the Beijing fest. The following is a condensed version of the conversation.

Why, after all these years, are you back in China? And how did you get interested in China in the first place?

Let’s say that I decided to take myself full circle, to go back where I started.…

When I was 14 I decided to study Chinese. Which meant I was prepared to be in the first batch of exchange student scholars the Italian government decided to send to China. I was really geared for that. I was never a full-fledged left-wing militant, but the politics played a role. Everyone then was imaging things about the Cultural Revolution; they had a complete fantasy version of the Cultural Revolution at that time.… [In addition] it was really high time for Oriental philosophies. This is what prevented me from becoming a full-time radical militant -- the fact that I was already so interested in the eastern Asian strain of thought. It always kept me at a certain distance from the overall radical politics of the Cultural Revolution.

When and why did you come, and how did it change your life?

I arrived at the end of 1974. I came to Beijing first. I was very naïve. I did not fully believe in the Cultural Revolution. … My major was anthropology, so I had filed a request to continue my research and do an M.A. at the Academy of Social Sciences. Only after I arrived, I discovered the academy had been shut down as one of the “strongholds of feudal thinking.” I had no alternative, so I had to request to be sent to a regular university to continue my research, and at that time, anthropology and ethnology were regarded as the “stinky four olds,” so the only thing I was offered was to go to Liaoning university [in the northeast] and study “mass literature.” So I went. And it’s only because I accepted that eventually this whole dramatic change in my life happened and I got involved in film and film studies.

What did your studying consist of?

I went with my fiancée at that time. … When we arrived, we realized there was very little we could do that would amount to a serious continuation of our studies. There were just two or three textbooks. You could not go beyond those three books. Not just the public libraries, but also the university libraries, were not open to foreign students. If we needed a special book out of the library, we had to ask our teacher. He would have to file a written request explaining why that book should be loaned to a foreign student. So we started going to see movies.

You got married in China in 1976; what was that like?

My fiancée and I decided to marry because at that time in China it was almost impossible to have a relationship, a sentimental relationship, and not be married. … The municipal authority that married us was a revolutionary committee. There were no taxis, so we took the bus to the wedding. And we could not bring any friends. It was a very sober ceremony. You simply had to sign. My first wife is French, so one person from the French Embassy was there and one person from the Italian Embassy was there. We were lucky because at least they were allowed to take pictures. Otherwise no wedding pictures were allowed at that time.

When we did our party with our friends, our colleagues, our fellow students from the university, it was a meeting with tea. No snacks. Just candy. Maybe lemonade. That was it. Later we insisted, we really wanted our foreign friends to enjoy and to celebrate with us, so we found a friend to loan us an apartment and we cooked a meal. We ate duck or something.

So did you really study?

We were studying but then we were sent to the countryside, to the factories, to do some manual work. We did everything -- worked in textile factories, steel plants, machine tool factories, and the countryside, transplanting rice. We picked apples.

What kind of movies did you watch?

For a number of months, the only movies we could see were North Korean, Albanian, Romanian, plus a few Soviet classics from the Stalinist period. We felt simply by watching the few revolutionary Chinese films that were around that there must have been a tradition. There were 11 films adapted from 11 revolutionary operas that felt quite stiff. Then we saw one called “Boulder Bay.” And we felt, OK, there is something special. At that time, those revolutionary films, the credits could not say who made it -- it was just a collective signature.

Then I discovered that the man who would become my teacher and my inspiration in the first phase of my work in Chinese cinema had directed the film. His name was Xie Jin. [He died in 2008.] By that time I had moved to Nanking and we were studying modern and contemporary history. That had happened right after the downfall of the Gang of Four. All of a sudden, by dozens, the old films came back to screens.

We started understanding that there was a certain style corresponding to a studio. ... You could really see, oh Shanghai studios, under them there’s Heavenly Horse studio and their films are more interesting than others. Let’s see if we can find more from that particular studio.

In my last year I got criticized many times by the political cadres who were taking care of foreign students, because I not spending most of my time in the university, but watching films. But when I returned to Italy, I was already set, I had decided to continue my research into the Chinese cinema, and I wanted to share the emotions we had felt with other people.

You left China in late 1977. Once you were back in Europe, you programmed a large retrospective of Chinese cinema.

I did not decide to become a full-fledged festival manufacturer until I could see there was the possibility to create a large-scale event entirely devoted to Chinese cinema. … It was one of the events that kickstarted interest in the West in Chinese cinema. It was called Electric Shadows, 1981. I borrowed the name from a very important book, the most important book that had been written at that time, by Jay Leyda. At that very early stage, we discovered that some titles were regarded as lost by the China Film Archive. So I went hunting. The first destination was Hong Kong. One of the best collections that I did find was through the World Theater in San Francisco, the oldest Chinatown movie theater. Another amazing collection existed in Golden Eagle Theater in the Chinatown of Havana. It was a fairly complete retrospective of the development of Chinese cinema -- 135 titles.

Over your years at Rotterdam, Locarno, Venice and Rome, you expanded your interest beyond Chinese cinema.

I decided it would have been idiotic to limit myself to what I knew about Chinese cinema. I wanted to be more specific about the contact between Chinese cinema and the other Asian cinemas. I started visiting these countries, like Japan. … Then I needed to know more about Soviet cinema. Then I decided I needed to go deeper into studying U.S. films.

But I never lost touch with Chinese filmmakers. Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige. … I met with them when they were in their second year as Beijing Film Academy students. The same would apply to a number of Hong Kong and Taiwan filmmakers.

What’s the identity of the Beijing festival?

There’s something quite similar to the way I tried to work on the potential conflict between Venice and Toronto [which often overlap in early September]. We would do a lot of work in Venice to create attention for specific titles that would then be put on the right track for a wider market recognition that would happen in Toronto.

What could happen here is that this could really become a platform for films to be fully appreciated within the Chinese market but in general also in the overall East Asian market.

One of the big questions hanging over Chinese film festivals is censorship. What kind of programming constraints did you face? And artistically, can festivals in China be taken seriously given China’s censorship rules?

I felt quite at ease with accepting this job. I knew that it only be a gradual process to see that slightly bolder things would be included in the films that would pass the censorship. It’s not a problem of self-censorship on our part, but we knew that we had to submit a limited number of titles for the final lineup.

[Normally] there are four levels of selection committees. When I convinced the political leaders of the festival that we really needed to create the concept of an official selection as something separate from the panorama and all the other sidebars, they also accepted the idea that not only the films could be directly sent to the final level, the top level, the executive committee, but also that we could discuss our choices with the executive committee, which amounts almost to discussing directly with the censors.

The executive committee is composed of very serious individuals from production and distribution, and serious researchers and professors. They are very knowledgeable about film. So whenever we wanted a special film that was slightly bolder than the others to be submitted to the censors, very often they said, ‘OK, we should try. It may not work, but we should try.’ And I think eventually this is the kind of continuous, this is the testing ground where we will have to experiment in the future too.

Part of censorship here is about explicit sex scenes, lengthy depiction of sex. Where it becomes really difficult is to fathom the political correctness or incorrectness of certain films. But in that sense we did not find it difficult to have some of the films that we had loved to be accepted by the censors. Our programmers saw more than 500 titles; we chose 40 titles, knowing that those 40 would be reduced to 20. But it did work. The variety of experiences that is represented is very different than in the past.

What is the role of the festival vis-à-vis Chinese films?

This is something you will have to ask to [organizers]. The first agreement we did strike is that there is us, a foreign team of programmers, focused on the international selection, but we must leave Chinese films alone.

Are you coming back next year?

I told them, let’s do this test year. After the festival we’re going to have a two-day seminar to wrap up the experience and discuss the future; there are a number of questions that need an answer, starting with the possibility of changing the dates of the festival. You know, to have a festival that would like to grow and become a major platform happening right before the Cannes film festival and Cannes film market, it’s almost impossible. ... I’ve thought of a number of [alternative] dates.

Tell us about the opening film, “Wondrous Boccaccio” by the Italian auteurs Paolo and Vittorio Taviani?

It’s what I was really hoping to find. It’s a very solid, serious film, by an old master. It’s film that could appeal to a Chinese audience. In this case it’s a literary adaptation that most of the well-educated Chinese have read in one version or another; “The Decameron” has been translated many times into Chinese. … When the Tavianis decided to make an adaptation of “The Decameron,” it’s because they wanted to look at the past as a comment on the present.

And then at the same time the film really works as a beautiful costume spectacle, which is what we needed for here. … So let’s say it’s a well known literary work from Europe, it’s a lavish spectacle, a costume drama and a certain level of political and social commentary.

Follow @JulieMakLAT for news from China

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.