Boiling Point: A trip to the Rockies

- Share via

This story was originally published in Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change and the environment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Walking along the Big Thompson River in Estes Park, Colo., over the weekend — the channel swollen with swift-moving Rocky Mountain snowmelt, a lush green slope on one side and local businesses on the other — I counted myself lucky.

A few days earlier, the Colorado Supreme Court had struck a blow against public access to waterways, tossing out a lawsuit aimed at allowing members of the public to wade and fish in riverbeds that run up against private property, as the Colorado Sun’s Jason Blevins reports. Fortunately, the Big Thompson was part of the fabric of downtown Estes Park. It helped me relax.

And it blew my mind, knowing these waters would eventually reach the Gulf of Mexico, by way of the Mississippi River.

I was in Colorado for a wedding, and as usual when I travel, I found myself mulling over recent environmental news.

Driving past electric lines, I thought about Xcel Energy beginning construction in Colorado on one of the few major transmission projects being built in the West. I also thought about the company getting sued after officials determined the most destructive fire in Colorado’s history was sparked in part by an Xcel power line — an assessment with which the company disagreed.

Over dinner at the wedding, I chatted with a staffer at a California regulatory agency that works on climate change, and with an engineering student researching perovskite solar cells — all of us coincidentally seated at the same table. The world is small.

Taking off from Denver International Airport early Monday, I admired the snow in the Rocky Mountains, knowing I would soon be back in L.A., drinking water that had flowed off the other side of those mountains. I reflected on a new analysis by my colleagues Hayley Smith and Sean Greene finding that Californians managed to reduce water use just 7% during the recent drought.

Nevada lawmakers, meanwhile, just passed a bill allowing government officials to cut off water to homes that use too much — at least if the drought situation gets worse on the Colorado River, per the Las Vegas Review-Journal’s Colton Lochhead.

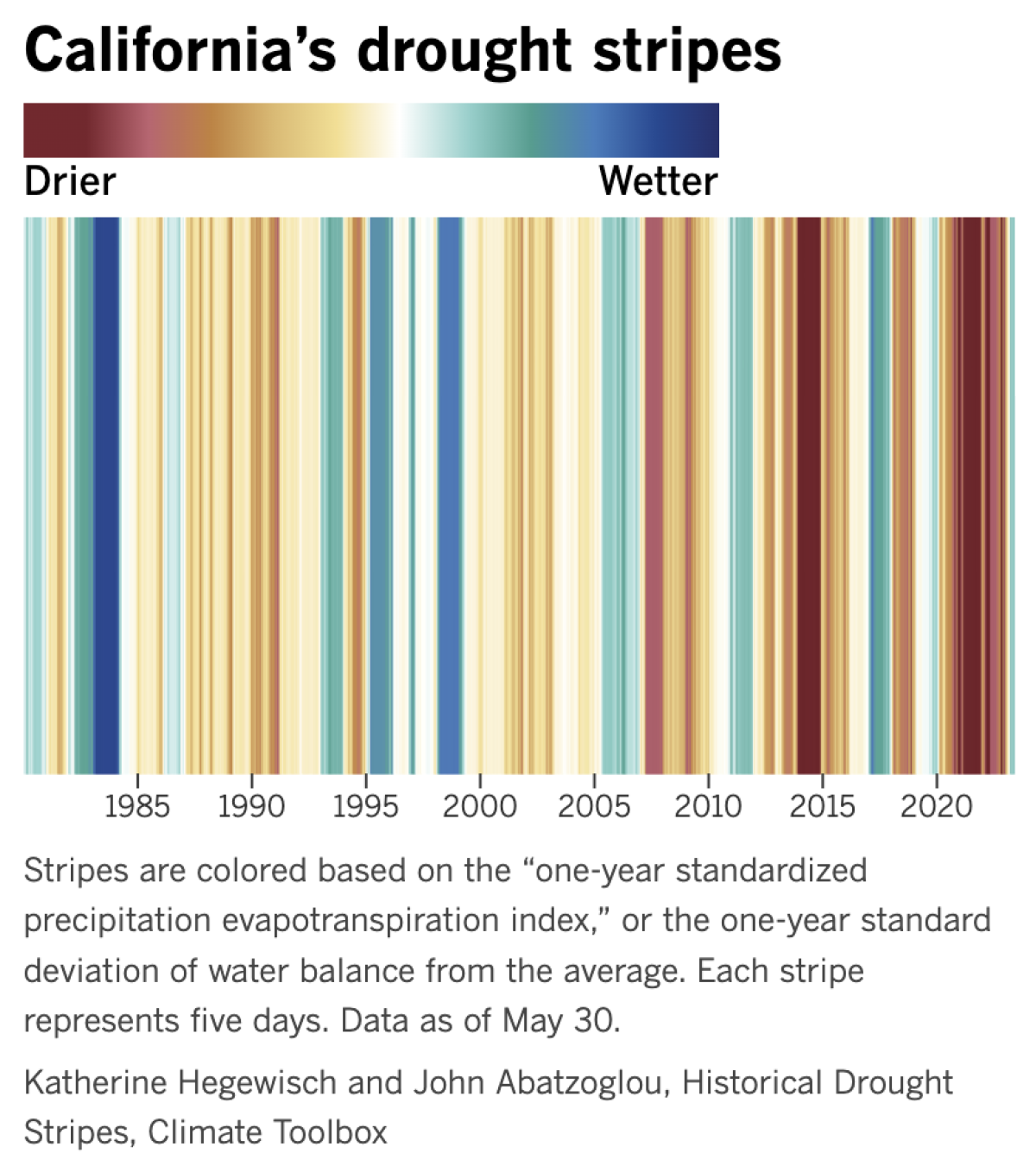

But what is drought, anyway? Just before my flight took off, I saw this chart by Sean Greene:

As Greene writes, it matters less and less exactly when a “drought” starts or ends, and more and more that the climate crisis is fueling a long-term dry trend in California and across the West. Many of our rivers and reservoirs are in good shape right now, but groundwater aquifers are still dangerously depleted, my colleague Ian James writes. And more dry years are coming.

Tearing out lawns can save lots of water — but even water-smart landscaping has its limits. A new ProPublica analysis finds that Las Vegas can’t save nearly as much water removing grass as the Southern Nevada Water Authority has claimed.

In New Mexico, meanwhile, a coal-plant closure means water from a Colorado River tributary can instead go to two tribal nations and the city of Gallup, as Hannah Grover writes for NM Political Report. But there are only so many coal plants to shutter.

Agriculture, of course, is the elephant in the room — with hay in particular consuming huge amounts of water.

When the wedding got underway, though, I managed to clear my mind and admire the Colorado scenery. The Rocky Mountains foothills were gorgeous. An overcast sky threatened rain, but the precipitation held off until just after the ceremony.

Humanity’s trials and tribulations would have to wait another day.

On that note, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

A nonprofit is planting tens of thousands of tiny giant sequoia seedlings in a stretch of Sierra Nevada decimated by fire, in hopes of restoring a hillside so badly burned the beloved trees might not otherwise grow there again. Here’s the amazing story by my L.A. Times colleague Alex Wigglesworth, who writes that while only a few seedlings are likely to become monarchs — the largest-size class of giant sequoias — the scientific lessons learned could be invaluable. In other wildfire news, the insurance company State Farm — which says it will no longer sell new home insurance policies in California, partly because of climate-fueled fire risks — reportedly has tens of billions of dollars invested in fossil fuels. Congressional Democrats are investigating State Farm and other insurers for their continued backing of coal, oil and natural gas, the Washington Post’s Brianna Sacks writes.

After being forced by a California wildfire to evacuate more than 140 cows, pigs, ducks and more, Nate Salpeter and Anna Sweet moved their animal shelter from California to New York. Now they’re once again under siege by smoke, my colleague Kwasi Gyamfi Asiedu writes. Their story is just one glimpse of the wildfire smoke blowing in from Canada and besieging the East Coast, along with postponed baseball games and electric utilities being forced to burn more planet-warming natural gas to make up for diminished solar-panel production. The Times’ Alexandra E. Petri wrote about how Easterners can protect their lungs and otherwise stay safe, based on lessons we’ve learned from years of terrible wildfires in the Golden State.

“You wanted to write a story about the ‘big melt,’ right? You’re hip deep in it now!” My colleague Jack Dolan climbed the highest peak in the Lower 48, Mt. Whitney, after a winter of record Sierra snow — via the extremely challenging Mountaineer’s Route, the first known ascent of which was by John Muir. Read Dolan’s wild story, which serves as a warning to anyone looking to hike Whitney right now without tons of training (and possibly an experienced guide). Also check out this illuminating visualization of California’s immense snowpack and where it’s going as it melts, from The Times’ talented data and graphics team.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

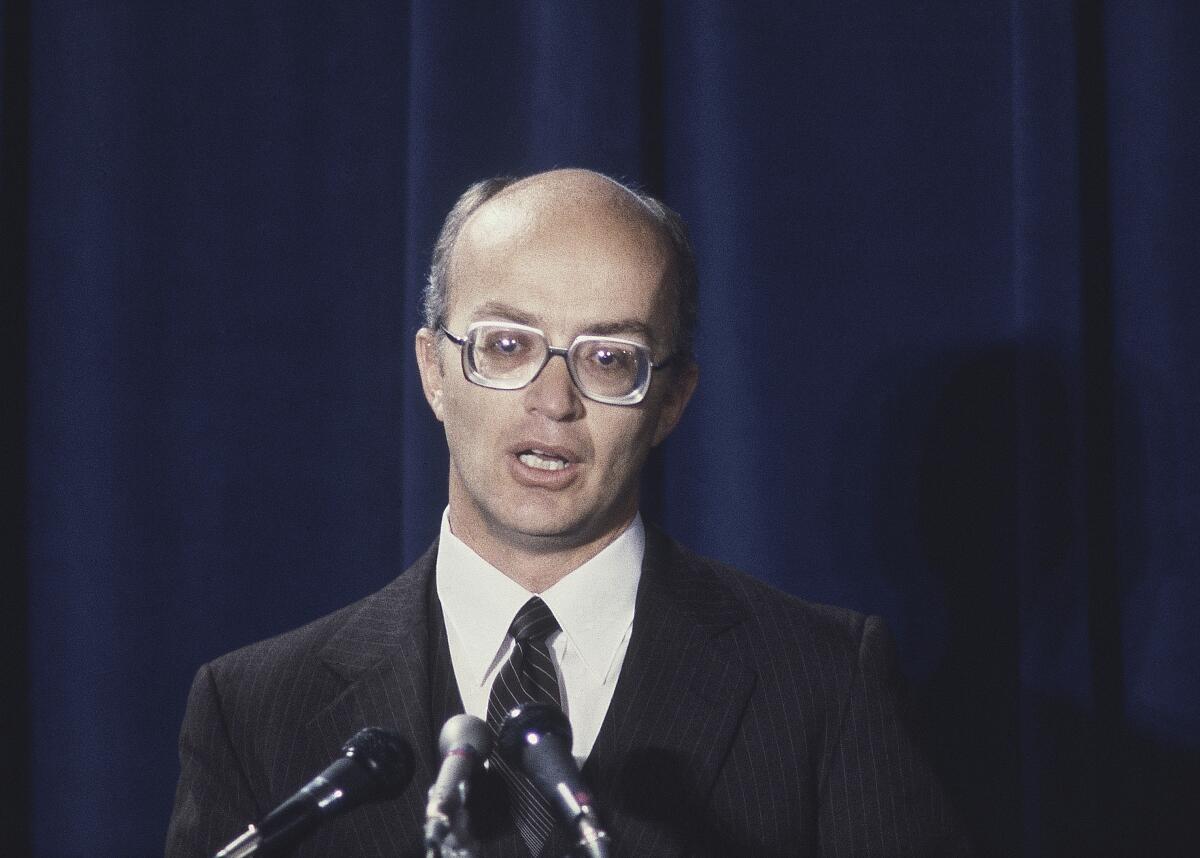

Former Interior Secretary James Watt — a Reagan appointee and key figure in the Sagebrush Rebellion, which sought to unwind federal ownership of Western lands — died at 85. “The battle’s not over the environment. If it was, they would be with us,” Watt once said, referring to environmentalists. “They want to control social behavior and conduct.” For more on Watt, here’s an obituary by the Washington Post’s Emily Langer. And for a reminder that bipartisan environmental action is not completely impossible, despite Watt’s legacy, here’s a story by Caitlyn Kim for CPR News, about a new bill from U.S. Sens. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) and Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) that would increase funding for projects that restore forest health and reduce water pollution.

The Long Beach port is getting $30 million from the Biden administration to electrify tractors and cut pollution — but on the condition that the equipment must be operated by humans. Details here from Reuters’ Lisa Baertlein. I can only imagine that unions will ask for this kind of deal more frequently as automation continues to proliferate. The Biden administration also plans to lend an Idaho company $850 million to build a battery manufacturing plant in Arizona, Reuters’ David Shepardson writes.

In a big win for public access to the California coast, state officials approved an agreement with two homeowners that will make it easier for the rest of us to get to the beach in Malibu, ending a 40-year struggle. “It’s so hard for us to get new access to the coast, and new vertical accessways are like unicorns — they just don’t exist, especially in Malibu,” said Lisa Haage, chief of enforcement for the California Coastal Commission, as reported by my colleague Hayley Smith. “Settling this case without litigation is huge. This is like flying to the moon or something.”

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm paid a visit to Southern California’s shuttered San Onofre nuclear plant, where she announced $26 million in funding to seek out communities that might want to take responsibility for storing America’s nuclear waste. Here’s the story from Rob Nikolewski at the San Diego Union-Tribune. Finding a place to store nuclear waste is especially difficult given what Ralph Vartabedian describes as “the nation’s failure, nearly 80 years after the Second World War, to deal decisively with the atomic era’s deadliest legacy,” in a New York Times piece revealing the federal government may abandon its promise to thoroughly clean up the Hanford site in Washington state. Back in California, meanwhile, officials took another step toward keeping the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant open past 2025, the Santa Barbara Independent’s Jean Yamamura writes.

The California Public Utilities Commission is finalizing “community solar” rules that could help medium-size urban solar installations take off — with utility bill savings for low-income homes. Details here from LAist’s Erin Stone, who quotes an activist as saying community solar is “really the necessary path for a majority of low-income communities and renters who don’t have the capital credit or home ownership to install solar panels on their roofs.” Another California agency just set an ambitious goal for “load shifting,” which basically means encouraging homes and businesses to use less electricity when the grid is stressed and more electricity at times of day when there’s tons of wind and sunshine, as Utility Dive’s Kavya Balaraman explains.

A court has ruled Sempra Energy board members can’t be held personally liable by shareholders for the Aliso Canyon gas leak, which spewed planet-warming methane and other chemicals over L.A. neighborhoods. The ruling was highly technical, with one of three judges dissenting, per the Metropolitan News-Enterprise. Sempra is the San Diego-based parent company of Southern California Gas Co., which owns the Aliso Canyon storage field. In less-than-ideal news for the gas industry, Utility Dive’s Robert Walton reports more American homes bought electric heat pumps than gas furnaces for the first time last year.

AROUND THE WEST

U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif.) visited the lead-contaminated neighborhoods around the former Exide battery plant in L.A. County and urged federal officials to make the area a Superfund site. But local activists are skeptical that Padilla’s demand will make much difference, my colleague Tony Briscoe reports. Up north, meanwhile, Bay Area officials say the heavy metals that were rained on communities by an oil refinery over Thanksgiving don’t pose a major health risk. Again, Briscoe has the story.

A groundbreaking new study has found toxic chemicals — including cancer-causing benzene — leaking from abandoned oil and gas wells. The study took place in Pennsylvania, as Liza Gross reports for Inside Climate News, but it’s got huge relevance to other fossil fuel-producing states. States such as California, where Chevron says it will appeal after being ordered to pay $63 million for covering up a chemical pit with benzene in it. And states such as New Mexico, where Navajo landowners protested U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s visit to Chaco Culture National Historical Park, saying her drilling moratorium on federal lands around the park will make it harder for them to profit off oil and gas, as Susan Montoya Bryan reports for the Associated Press.

Federal prosecutors sued Southern California Edison, saying the company’s power lines ignited the 2017 Creek fire in Angeles National Forest. The federal government had previous brought suit against the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, claiming the city-run utility was to blame. But prosecutors seem to have changed their minds about who started the fire, as Edvard Pettersson reports for Courthouse News Service. The feds are seeking more than $40 million in damages from Edison.

ONE MORE THING

Southern California has had plenty of destructive earthquakes in recent decades. But why hasn’t there been a huge rupture along the southernmost tip of the San Andreas fault — causing an earthquake of magnitude 7 or greater — in about 300 years?

A new study finds a surprising possible answer: the lack of water covering the Salton Sea region.

The southern end of the San Andreas, near the U.S.-Mexico border, has historically been inundated by occasional Colorado River floodwaters, which have periodically created a lake much larger than today’s Salton Sea. Those waters may have contributed to strain on the underground fault line, helping to trigger mega-quakes, as my colleague Rong-Gong Lin II explains.

Does that mean we’re less likely to get a destructive temblor in L.A.? Unfortunately not. The southern San Andreas will eventually rupture — and when it does, the delay could mean an even more powerful quake than we might have felt otherwise.

We’ll be back in your inbox on Thursday. To view this newsletter in your Web browser, click here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on Twitter.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.