Adult orphans: when parents die

- Share via

JEANNE SAFER loved and revered her mother, and braced for impact as the seemingly indomitable woman’s mind and heart began to fail seven years ago. But ready or not, the end came in December 2004. Esther Safer rallied long enough to exult to her daughter, “This is my day!” then died peacefully at 92.

At 57 -- her father having died many years before -- Jeanne Safer became an orphan.

As a psychotherapist in New York City for 30 years, Safer had heard countless patients talk about the effect their parents’ deaths had on them. She anticipated the sadness, the heightened sense of her own mortality, the comfort taken in her mother’s bequeathed treasures. But in the months and years that followed her mother’s death, she began to confront in herself, and to recall from the accounts of many patients, something unexpected, a “shocking -- almost sacrilegious” truth:

The death of your parents can be the best thing that ever happens to you.

That provocative assertion became the opening line of “Death Benefits,” an autobiography-cum-guidebook Safer has written about that most momentous of midlife passages -- becoming an adult orphan. The book, published by Basic Books, is due in bookstores this week.

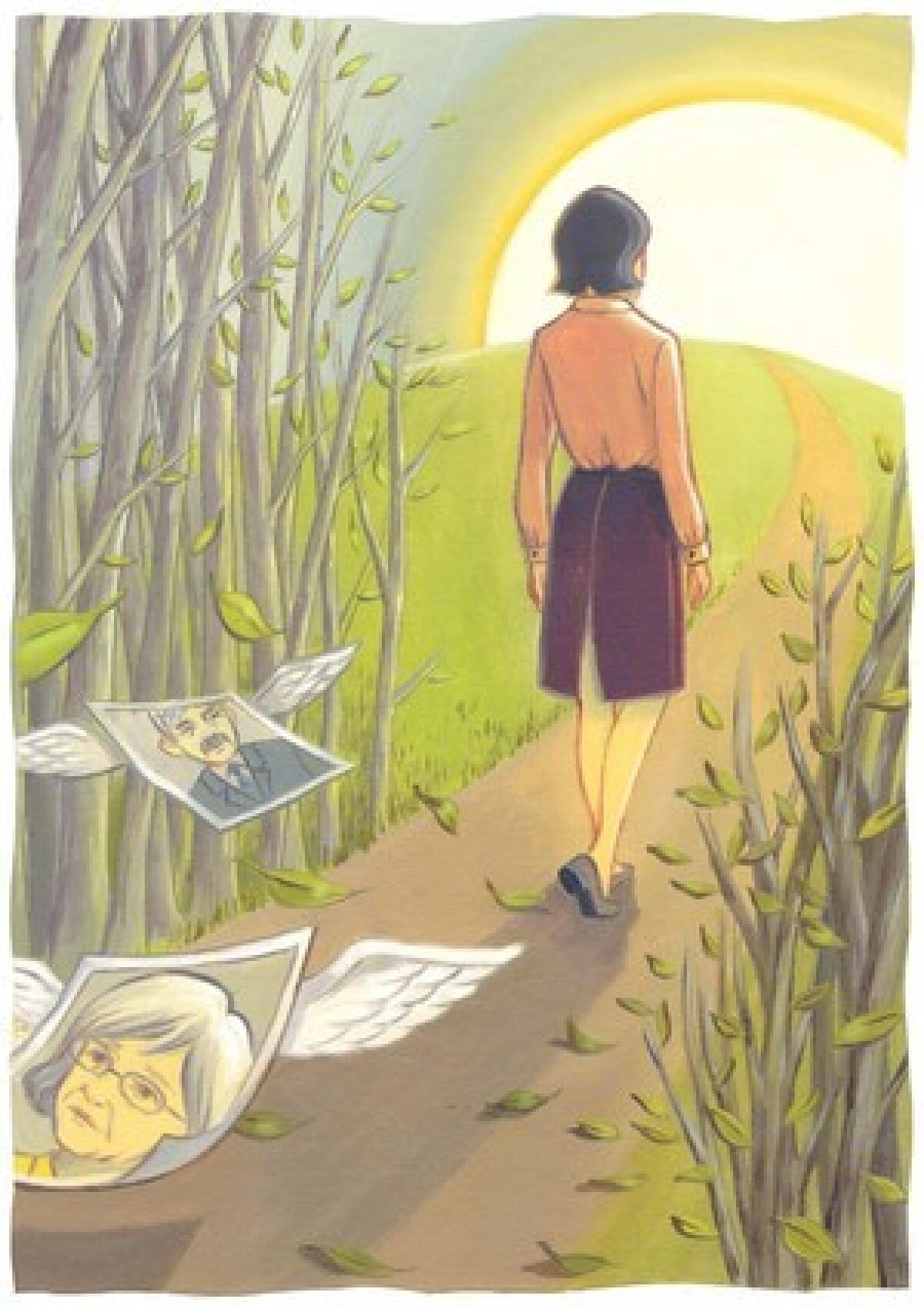

“The death of a parent -- any parent -- can set us free. It offers us our last, best chance to become our truest, deepest selves,” Safer writes. “Nothing else in adult life has so much unrecognized potential to help us become more fulfilled human beings -- wiser, more mature, more open, less afraid.”

And maybe healthier too. Safer and other health professionals point to legions of adults in midlife whose parents’ deaths inspired them to lose weight, tidy up poor health habits, get help for depression or anxiety, pursue new passions and shoulder responsibility for their physical and mental well-being.

Dr. Howard Brody, a family physician for 30 years who now teaches ethics at the University of Texas Medical Campus in Galveston, remembers bracing for near-daily visits from one of his most needy, hypochondriacal patients after learning that the woman had lost both of her parents in the span of a month.

What he got instead was a lesson in death benefits.

“I was quite shocked when a new person, for all intents and purposes, walked into my office for her next visit,” Brody reported. “This new person seemed much more confident and willing to take charge of her own life, and not to seek medical remedies for whatever ailed her.” In her late 40s, this patient, who had long seemed incapable of taking steps to improve her life and health, had joined a church group, made new friends and appeared to be seized by a new sense of purpose.

Though virtually universal, the adult experience of parental loss has been little studied. That is, in part, precisely because it is universal, and therefore perceived as a normal process, says Debra Umberson, one of the few who have conducted research on the phenomenon. Adult children, having seemingly established their independence, were long thought to absorb the expected blow and move on to tend to relationships with the living.

Safer’s book, however, comes amid an evolving view of this adult milestone. Increasingly, research psychologists and those in clinical practice see the loss of elderly parents as an event that not only touches off an emotional reaction that is real and long-lasting, it also is often the beginning of a continuing, though wholly different, relationship with the dead.

At any stage of adulthood, losing one’s parents can bring death benefits, Safer says. The adult intent on making the most of a parent’s loss should be willing to examine her parents’ emotional legacies carefully and consciously. Doing so, she argues, will better distinguish those parental legacies worth keeping -- the ones that contribute to health and well-being -- from those that no longer serve that end. The age of the adult matters less than his willingness to do that sorting “in a mindful way,” she says.

But in recent decades, profound demographic changes have made orphans in midlife the most common, and most receptive, beneficiaries of death benefits.

As improved healthcare has pushed average life expectancies up into seven decades, parents have begun typically to live well into their children’s adult lives. Today, one-third of American 50-year-olds have a father still living and two-thirds still have their mother. But by the time they turn 60, two-thirds of Americans will have become adult orphans.

In short, midlife has become a time of loss -- and, Safer argues, of potential gain. As these increasingly older parents die, they are leaving children who have established mature identities but are on the cusp of new transitions. They can anticipate many more years -- in many cases decades -- of active life. But much of the hardest work of early adulthood is behind is them. Their own children may be leaving the home or having children of their own; their careers have often peaked or are in a state of flux; retirement looms and new horizons beckon; and as their bodies change and relationships shift, their self-images are primed for transformation.

“Parent loss,” Safer writes, “is the most potent catalyst for change in middle age.” And because they have experienced so much of life by that point, these bereaved children can see their parents with more wisdom and greater understanding.

“Finally,” she writes, “we can empathize.”

Often, the death of parents brings an end to a period of intensive caregiving, freeing up time and emotional energy for an adult child to attend to his or her own needs. And with their parents gone, many adults keenly sense that they are “next in line” for decline, disability and demise. That often concentrates the mind on what’s right, and wrong, in their lives -- what traits and behaviors have served them well and which would better be abandoned.

With the prospect of several decades -- and whole chapters -- of life ahead, these adult orphans can and often do rechart the course of their lives, reassess their priorities and sometimes reject the parental expectations (whether of achievement or disappointment) that powerfully shaped the opening and middle chapters of their lives.

Negative effects

FOR MANY bereaved adults and those who study them, Safer’s conviction that parents’ deaths present a golden opportunity for healthful change flies in the face of much apparent evidence.

“On average, it has adverse effect on adults -- all kinds of adults,” says Umberson, a University of Texas at Austin sociologist who has conducted extensive research on family relationships and health. For three years, and often as many as seven, the adult children of parents who die are much more likely to increase their alcohol consumption significantly, take poorer care of themselves and become anxious or depressed, Umberson found in three comprehensive surveys of adults surviving a parent’s death. Her findings are the basis for her 2003 book “Death of a Parent: Transition to a New Adult Identity.”

But Umberson, whose research was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging, also found a potential silver lining in a parent’s death. Around the seven-year mark after their parental loss, “they do get better,” Umberson says. Many of those she surveyed reported a marked improvement in health and healthful behavior.

“A lot of people change very deliberately. And sometimes unconsciously, they change in ways that they think their parents would admire, or to become more like the person their parent would want them to be,” Umberson says. “Sometimes people incorporate the good parts of their parents in ways that are very constructive for self-growth.”

But Safer and Umberson each argue that adult children would do better to be deliberate about cultivating death benefits, both before parents die and after their passing.

Where possible, being intentional would mean confronting some difficult tasks, and truths, when a parent is still alive.

“You can try to resolve things, and say the things you would want to say to parents before they die,” Umberson says. Too many people, she says, shrink from doing so because they would prefer to shield themselves from the uncomfortable reality that their parents will die. “But it makes people feel really good when they’ve done that . . . . I’ve seen people who deeply regretted not having resolved things with one parent who died, and then not doing so with the parent who’s still alive.”

Safer calls that process preparing for “the deathspace” -- “a place of seismic movement” that adult children wishing to reap death benefits must enter after the death of one parent or both. In it, she wrote, “truly terrible parents lose their power. . . . Children whose mothers or fathers were guilty of more routine crimes of the heart feel sympathetic and even come to identify with them. Flawed parents are discovered to have hidden virtues and idealized ones to have serious flaws.”

In short, the basis for an honest, adult relationship with one’s parents -- at last -- is often established in the deathspace, Safer says. But because “all further communication with them is unilateral,” she notes, adult children gain an upper hand in that relationship: They can chastise or forgive their parents, reinvent them, accept some of their lifelong advice and disregard the rest. In the process, they can mature and learn to stand on their own, she says.

Reviewing legacies

SAFER’S effort to reap “Death Benefits” started with a painstaking review of her mother’s personal history and her legacies -- good and bad. In their 57 years together, Esther Safer had taught or given her daughter fierce persistence in the pursuit of goals, a love of writing and music, and a penchant for decorating with red. But she also cast her daughter in a compulsory support and cheerleading role. And this midcentury, middle-American mother became helpless at any sign of physical infirmity in her only daughter.

The result was a daughter determined enough to have earned a doctorate in psychology, built a successful psychotherapy practice in New York City, written four well-regarded books and made herself and her husband a New York City sanctuary that is lovingly layered with exotic and distinctive treasures. But beneath her seeming confidence lay a vulnerability she could not explain until recognizing it as a legacy from her mother: Jeanne Safer had an enduring and inconsolable anxiety about being or becoming physically weakened or ill.

While Safer’s husband gamely battled cancer, Jeanne would become undone by a common cold or a sudden headache. For years, Safer’s irrational distress flummoxed her. “My reaction to certain kinds of adversity made me feel weak and helpless and fraudulent; a psychoanalyst incapable of penetrating the most wounded part of her own psyche is like an out-of-shape personal trainer,” Safer wrote in “Death Benefits.”

As Safer conducted this personal inventory after her mother’s death, she found that some of her mother’s emotional inheritances were worth keeping. Others, Safer wrote, had not served her well. And once she recognized their source and understood their effect, Jeanne Safer decided they should be abandoned. Like a parent’s ratty, old easy chair, the psychological fallout of Esther Safer’s inability to console her daughter in sickness would simply have to be left behind.

On the same curb, Jeanne Safer vowed she would try to leave her mother’s penchant for perfectionism and her inability to forgive friends or family who let her down -- both tendencies Jeanne saw in herself. Accept flawed love, Safer told herself, and remember that family and true friends accept you, flaws and all.

Finally, as she looked hard at her mother’s life, Safer saw something else she wanted to leave behind: a fear of abandonment that had dogged her mother from childhood into adult life. This, Jeanne came to understand, was why her own visits home as an adult were so often spoiled by her mother’s ire and accusations: All Esther Safer could do during these much-anticipated homecomings was to focus on the prospect of her daughter leaving.

Esther Safer focused on the likelihood of abandonment to protect herself from disappointment when it happened; for Jeanne Safer, that kind of catastrophic thinking prompted assumptions of life-threatening illness when she caught a bug or pulled a muscle. Once she recognized the source of “that hopeless dread” that so often threatened to engulf her, Safer says its power over her began to fade.

Only her mother’s death could open the door to such insights, Safer says. And only such insights, she adds, can open the door to changes in the way she thought about herself, acted on her feelings and behaved toward those around her.

“Death makes all the difference; it broadens your perspective,” Safer writes. “I had tried to see [Esther Safer] before, but until then, the effort of simply coping with her and the feelings she evoked got in the way. . . . Now I could see us together from a therapeutic distance -- beyond blame, beyond the frantic need to get through or justify myself, beyond disappointment, beyond rage -- beyond fear.”

A new kind of mourning

SAFER’S book reflects a view of bereavement that has evolved significantly in recent years. Until the 1990s, mental health professionals continued to take their cues from Sigmund Freud. In “Mourning and Melancholia,” published in 1917, the father of psychoanalytic theory conceptualized healthy mourning as a process by which the bereaved effectively detaches himself from the dead.

When that “decathexis” is accomplished, the bereaved can shift the emotional energy invested in that relationship with the deceased into bonds with the living. The relationship with the departed is effectively frozen in place, preserved without further development or further drain on the survivor’s emotional energies.

By the mid-1990s, however, a new approach to grief began to take hold in psychotherapy circles. Prompted by clinical observations and research evidence, mental health professionals began to see grief as a process in which the bereaved maintains an ongoing -- and evolving -- relationship with the departed. Conversations continue. But in addition to holding up her end of the exchange, the survivor gets to choose what advice the departed gives and what opinions the departed holds.

In this process, the bereaved regains power over a relationship that may, in real life, have been ambivalent, overwhelming, unsatisfying or unstable. She may derive strength from that ongoing relationship, alter it to suit her needs or, if necessary, strip it of power over her life.

“We don’t really ever detach from them,” said psychologist Dov Shmotkin of the Tel Aviv University.

A study by Shmotkin, published in 1999, underscored this point. Shmotkin surveyed several hundred Israeli adults -- ages 17 to 77 -- about the intensity and quality of their bonds to their parents. When he compared adult children whose parents were dead with those whose parents were still alive, he found something that surprised him: The death of parents did not diminish the intensity of their children’s reported bonds to them. Children whose parents were dead were just as likely as those with living parents to describe their relationship as close. The bond survived.

When Shmotkin looked at the reported quality of adult children’s relationships with their parents, he found evidence that that bond evolves beyond death as well. Those whose parents were dead rated their bond with those parents as more positive on average than did those whose parents were still alive. Though adult children with living parents were more ambivalent in how they felt about their parents, those whose parents had died were likely to see the relationship in rosier terms.

“It is idealization, which is keeping the best and throwing away the worst” about the relationship with parents, Shmotkin said. By casting that bond in a positive light, Shmotkin surmised, adult children prop up their self-images. The children of “such good, perfect, wonderful parents,” he surmised, would have to feel like good and worthy people -- and good parents to their own children, as well, he said.

Four years after her death, Esther Safer has become a source of pride, of encouragement and of ongoing advice to her daughter.

In life, Esther Shafer’s insistence on her daughter’s constant attention and admiration -- as well as her unbending pronouncements on good taste -- were a decidedly mixed blessing. With her death benefits firmly in hand, Jeanne Safer’s admiration for her mother is unambivalent. And those pronouncements on style -- muted by death and selectively observed by her daughter -- are accepted with unalloyed love and gratitude.

“Esther wouldn’t have it any other way,” her daughter says.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.