CSI Bethesda: Sleuths used sequenced genome to track down killer

- Share via

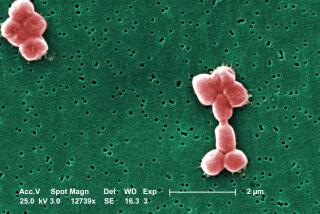

Patients were dying at the National Institutes of Health’s Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., and the suspect was an elusive and resilient strain of bacteria called Klebsiella pnuemoniae. But how could the infectious disease control sleuths at NIH’s research hospital collar the perpetrator and put an end to its reign of terror?

The answer, in this most forward-leaning of research institutions, was genomic sequencing.

Drug-resistant bacterial infections lurk everywhere in hospitals, with the comings and goings of sick people, tended by an army of medical professionals using common equipment including sheets, plumbing, CAT scanners and infusion pumps. And until now, infectious disease control experts have had a limited arsenal of tricks to defeat them, including strategies such as better hand-washing practices and making male physicians tuck their ties into their white coats.

Even when they thought they had captured a culprit creeping into several patients’ rooms, their means of proving it was all the same microbe was a crude test that couldn’t distinguish between two similar strains of bacteria.

But the sleuths at NIH grabbed the suspect bacteria and ran its genome to gain a definitive answer to the question: was this a serial killer or an series of unrelated infections? Where was the miscreant hiding, and how was it getting from room to room?

The genome-sequencing exercise allowed the sleuths to identify Klebsiella’s exact fingerprint matched -- and found it on 17 patients who were sickened while in the clinical center during the summer of 2011. It was carried into the center by a seriously-ill 43-year-old woman who was brought to the NIH to participate in a study from a hospital in New York.

Before it was eradicated, eleven of the 17 patients infected with it died -- six from the infection and five from their underlying disease, the NIH experts concluded. They discovered that the microbe was probably traveling between rooms after lodging in sinks and drains, some of which were ripped out and others of which were sanitized after an extensive eradication effort.

“Genome sequencing, as it becomes more affordable and rapid, will become a critical tool for healthcare epidemiology in the future,” said Dr. David Henderson, the NIH Clinical Center’s deputy director for clinical care. He predicted it would be “rapidly adopted” by other hospitals to track down and eradicate future hospital-borne infections.