A chandelier built of bicycle parts? It makes a statement

- Share via

Artist and designer Carolina Fontoura Alzaga turns unlikely trash into beautiful treasure.

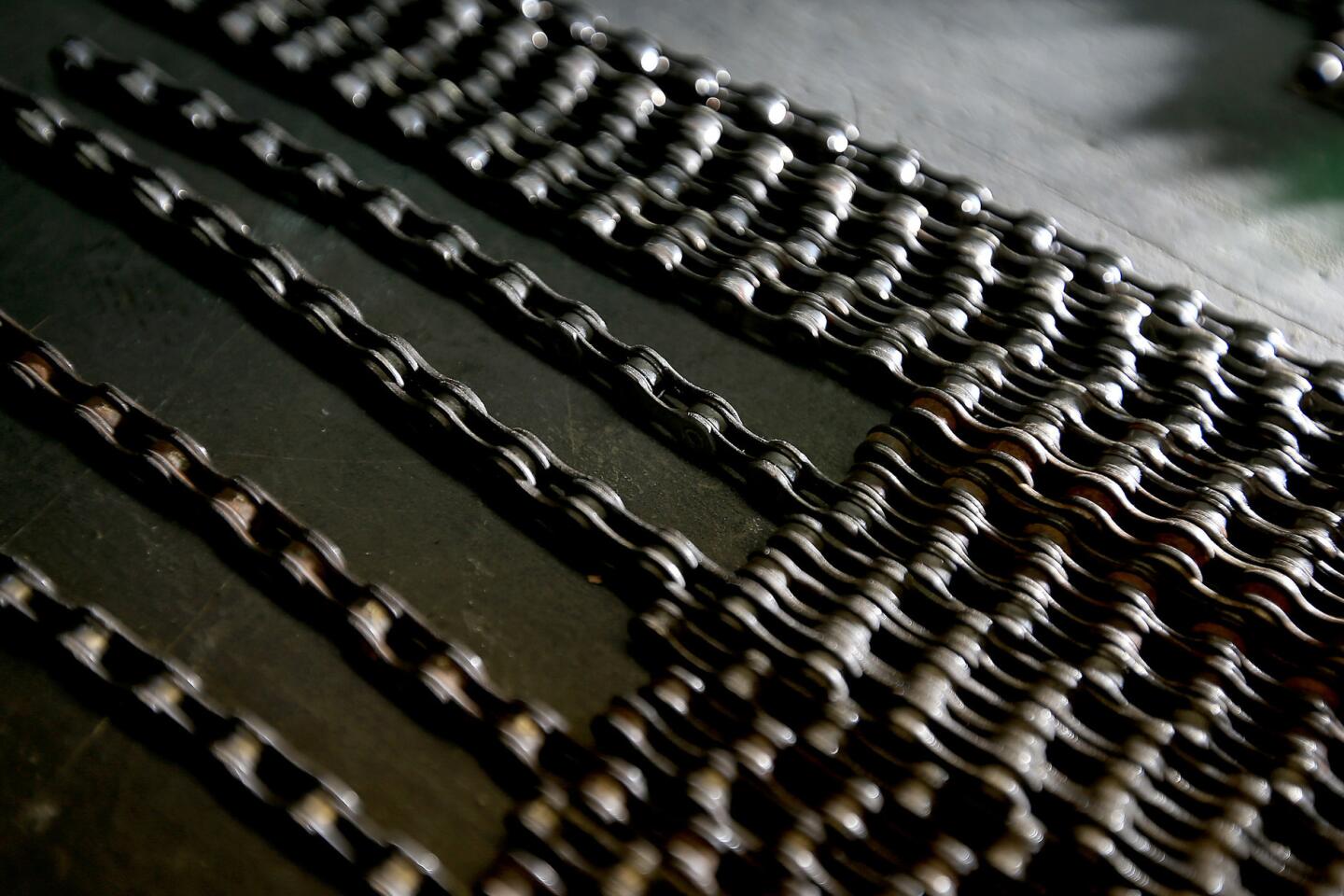

She collects used bicycle parts — chains, rims and such — from garbage dumps, junkyards and Dumpsters and from bins she’s placed at about 80 bike shops throughout Los Angeles. She cleans the metal parts and uses them to create chandeliers that are also urban fine art sculptures.

Her company, Facaro, ships the custom-made light fixtures all over the United States and to clients in Mexico, Canada, Norway, Ireland, Switzerland, Poland, Holland, France and Japan.

A 450-pound, 8-by-4-foot light fixture hangs in Sunset Plaza in Los Angeles; another custom 450-pounder drops from a ceiling in Bahrain. A custom chandelier was recently acquired by Neil Patrick Harris for his New York home. A recent project was for a Green Bay, Wis., theater.

She started the business in 2012 and began 2014 with a seven-month waiting period for her pieces, which sell for $925 to $22,000.

“Since its conception, the chandelier was meant to convey luxury and status through its scale as well as its ornately decorative and dramatic elements,” Alzaga says at her Boyle Heights studio, where she is dressed in worker coveralls. “I find that the allure of this bicycle chain chandelier exists because of the juxtaposition of its two disparate elements.”

She notes how those two elements — refined opulence and discarded trash — are alien on levels other than just the physical: the visual, emotional, even the political. The chandelier, she says, is a sign of splendor meant for the powerful classes — not generally the masses. Hanging discarded bike parts taken from the trash in place of the traditionally showcased bling is both a political and sculptural statement.

“Chandeliers are traditionally made from crystal, which is quintessentially fragile and refined and worthy of extreme care,” she says. “Castoff metal exists on the extreme opposite end of those spectrums. By combining extravagance and disposability in one object, the authority of one over the other is put into question.”

For now, the chains are cleaned but otherwise left au naturel, not painted or covered in any way. But Alzaga is playing with the thought of adding color, perhaps copper, silver, brass. Rims can be left original or painted black, though she prefers black. No two chandeliers are made exactly alike, although very similar styles can be created.

She says the bike chandelier, regardless of its size and scope, is a piece that opens one’s mind to combination possibilities that exist all around us, if we would take the time to rethink cultural rules and our role in consumption.

“Once you allow yourself to question what you were socialized to believe as immutable fact, then you have the freedom to reclaim your own ideas about what is deserving of extreme care,” she says. “To me this body of work is about transcending function and re-vindicating refuse. It’s a statement to challenge the manufactured necessity of the new, and to surpass externally and self-imposed limitations of beauty, vision and action.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.