Till Murder Do Us Part: Dan and Betty Broderick’s divorce played out over five vicious years

Dan and Betty Broderick’s divorce played out over five vicious years, was the talk of La Jolla. Betty finally put an end to it all -- with a .38-caliber revolver.

- Share via

Reporting from SAN DIEGO — Everybody in La Jolla knew the Brodericks. Daniel T. Broderick III and his wife, Betty, seemed to have a classic society-page marriage. Dan was a celebrity in local legal circles. Armed with degrees from both Harvard Law School and Cornell School of Medicine, the prominent malpractice attorney was aggressive, persuasive and cunning--a $1-million-a-year lawyer at the top of his game. Betty spent her days shuttling her four children to and from music lessons and soccer games, planning the couple’s busy social calendar and tending to the yard and housework.

In the early ‘80s, Dan and Betty were regular guests at the parties of the La Jolla in-crowd. “They both were almost central casting for early yuppie,” recalls Burl Stiff, the society columnist for the San Diego Union. “He always looked straight from Polo. She always had very pretty clothes--Oscar de la Renta and the like.”

But in 1983, the facade began to crack when Betty suspected that Dan was having a romance with his office assistant. In 1985, after 16 years of marriage, Dan filed for divorce, sparking five years of battles so violent that Broderick vs. Broderick became known as the worst divorce case in San Diego County. The jilted wife spray-painted the interior of the $325,000 hillside home they had shared. She rammed her car into Dan’s front door, left obscene messages on his answering machine and defaced court documents, writing “God” where his name should have been. Betty says Dan used his legal influence to win sole custody of their children, sell their house against her wishes and bilk her out of her rightful share of his income. More than once, Betty told her children that she would kill their father.

Dan countered by having Betty arrested, jailed and briefly committed to a mental hospital. He tried to control her by withholding from $100 to thousands of dollars a month from her support payments, docking her for behavior he deemed inappropriate, and he obtained a temporary restraining order to keep her out of his house. When she threatened him, he wrote her curt letters in the coldest legalese. If she tried to kill him, the letters warned, he would make Betty regret it.

On the first Friday in November, 1989, four days before Betty’s 42nd birthday, yet another round of legal papers arrived at her door. Dan was threatening to file criminal contempt charges unless she stopped leaving lewd messages on the answering machine he shared with his new wife, Linda. Betty recalls that she was exhausted by the near constant court battles, likening them to “putting a housewife in the ring with Muhammad Ali.” And late Saturday night, as the threats pounded “like hammers at my head,” she decided that she couldn’t fight anymore.

Just before dawn on Sunday, she dressed, got in her car and drove from her ocean-view home in La Jolla Shores to Dan and Linda’s Georgian-style house in Marston Hills, near downtown San Diego. She used her older daughter’s key to let herself in.

She climbed the stairs and slipped into the master bedroom, standing over the bed where Dan and Linda slept. Her eyes had not yet adjusted to the darkness as she pointed her 2-year-old .38-caliber, five-shot revolver toward the Colonial print bedspread and began firing--”real fast” she recalls, “no hesitation at all.”

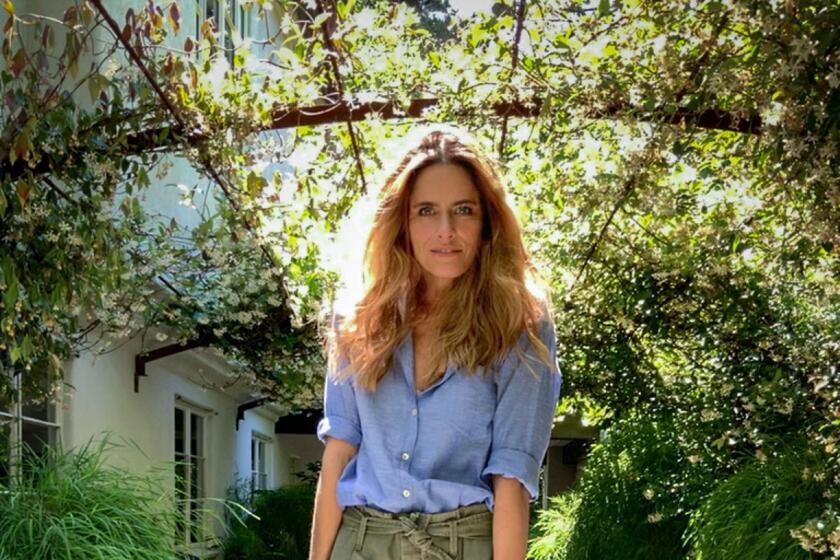

Amanda Peet, who plays infamous Southern California killer Betty Broderick in Season 2 of “Dirty John,” turned to writing after 40 — and it’s paying off.

One bullet hit a bedside table. Another pounded into the wall. But three bullets struck the sleeping couple. One pierced Linda’s neck and lodged in her brain. Another hit her in the chest. A third perforated Dan’s back, fracturing a rib and tearing through his right lung.

“OK, OK, you got me,” Betty heard Dan say. He dove to the floor, landing near the bedside telephone, and Betty says she thought, “Oh my God! He is going to be on that phone before I’m down the stairs.”

She yanked the phone out of the wall and fled.

THE KILLINGS SHOCKED San Diego’s legal community, for which the deaths of Dan and Linda were unwelcome reminders of the law’s limits. As Dan had told friends many times, if Betty was determined to kill him--and was willing to pay the consequences--nothing would stop her. The murders also resonated in La Jolla, where tales of the Brodericks’ messy divorce were as common as the sight of Betty’s four-wheel-drive wagon with the “LODEMUP” license plate.

Overnight, Betty became a symbol of the rage--and desire for revenge--so familiar to divorcing couples. At one La Jolla cocktail party soon after the killings, a man who attended with his second, younger wife on his arm joked: “I guess this is Be Nice to the Ex-Wife Week.” But many women saw themselves in Betty--a wife who refused to be broken when, at her husband’s whim, she was deprived of family, friends and a way of life.

When Betty first agreed to talk to me three weeks after the killings, she came on strong: “He went off with the bimbo at 40, driving a red Corvette--haven’t we heard this before?” she chirped into the telephone as we sat, separated by a plate-glass window, in the sterile visiting room of the Las Colinas Women’s Detention Facility. Betty was no longer the svelte, tailored woman that Dan had left behind--she had gained 60 pounds since the divorce. As she spoke, her words a rapid-fire summation of the previous six years of her life, she was intelligent, angry and without remorse.

If Dan had settled the divorce to her liking, she said, “I would’ve been fine. I would’ve had my house, my kids. I would’ve still worn a size 6. I could’ve done my ‘superior’ dance.” Eager to make her case, she jumped frantically from incident to incident. Even without the benefit of her voluminous divorce records, Betty recited names, dates and details to show just how ruthless she believed her husband had been: Dan, she said, had tried to drive her insane so no one would fault him for divorcing her.

“I have never had emotional disturbance or mental illness--except when he provoked a ‘disturbance,’ ” she spat. “My ‘emotional outbursts’ were only a response to Dan’s calculating, hateful way of dealing with our divorce. He was hammering into me and everyone else that I was crazy. . . . How long can you live like that?”

Soon after her story appeared in print, hundreds of people, most of them women, wrote to Betty and to local newspapers to say that while they didn’t condone murder, they understood the fury that prompted it. “I believe every word Betty says--because I’ve been there,” one woman wrote. “Lawyers and judges simply refuse to protect mothers against this type of legalized emotional terrorism.” Another wrote: “The inequities in court proceedings and financial settlements are . . . rarely believed or understood except by the women who experience them. Isn’t it time we take a good look at our courts and our system of divorce?”

Betty said that in order for me to understand the killings, I had to know the long history of her case--and with Dan and Linda dead, only she was left to tell it. Over the next six months, she called and wrote often, always eager to describe the “overt emotional terrorism” that Dan had inflicted upon her. At first, she talked only obliquely about the killings, which she called “the incident,” but eventually she called me from a public telephone at the jail and confessed.

In our first meeting, her eyes wide and her voice trembling, she insisted that she had been Dan’s victim and that all her actions were justified. “I was right! How could things go so wrong?” She answered that question by telling and retelling the story of a loving wife and mother duped, dumped and driven to violence by the man in whom she had invested her life. “I bought into a 1950s ‘Leave It to Beaver’ marriage . . . and he stole my whole life,” she would tell me later. “This was a desperate act of self-defense.” But as I struggled to understand, I discovered a more complex tale. The more pieces Betty Broderick added to her puzzle, the fewer seemed to fit.

This week, host Mark Olsen (@indiefocus) hands the mic to reporter Yvonne Villarreal (@villarrealy) as she interviews Alex Cunningham, the show-runner of Bravo’s new TV series “Dirty John.”

THE FIRST TIME DAN saw Betty, she says, he told friends that she would be his wife. She barely gave him a second look.

That was in 1965, just before her 18th birthday. She and a girlfriend had traveled from New York for a chaperoned football weekend at the University of Notre Dame, where Dan was beginning his senior year. He approached her at a party and introduced himself as an MDA--a doctor, “almost.” He said he’d be attending Cornell University’s medical school in Manhattan the next year. The conversation was brief, and when Betty returned to her first semester at Mount Saint Vincent, an all-women’s Catholic college in the Bronx where she was an English major, she remembers thinking Dan was a nerd.

“I’m real tall and used to go out with athletic guys,” she remembers, explaining that at 5-foot-10, Dan was nearly an inch shorter than she. “He had long skinny sideburns, round tortoise-shell glasses. You’re talking geek city.”

But Dan kept in touch, sending telegrams and letters to Betty, who was living with her parents in the New York suburb of Bronxville. And when the confident young medical student called her the next fall, Betty was intrigued.

Dan was the oldest of nine children from a strict Catholic family in Pittsburgh. His father, the grandson of an Irish immigrant, was the first Broderick to attend college--at Notre Dame. A naval officer and lumber wholesaler, he reared his five sons and four daughters sternly.

“My father was a disciplinarian, there is no question,” says Larry Broderick, Dan’s brother, who noted that all his siblings went to college--and every boy attended Notre Dame. “Our will to succeed is inherited. It’s genetic.” And Dan, says Larry, was the brightest in the family.

Betty liked that. “He was very ambitious, very intelligent and very funny. And I am those three things. We were from the same kind of background. We both wanted the same things in the future,” she says: wealth, social standing and a large family. “All I wanted to be was a mommy,” she says, and that appealed to Dan. “He promised me the moon. The guy asked me to marry him every day for three years.”

They were married in April, 1969, in an elaborate ceremony at the Immaculate Conception Church near Betty’s parents’ home. Photographs from that day reveal a bride of striking beauty--rail thin and wrapped in lace, with bright eyes, long blond hair and a satisfied smile. Dan, always fastidious about his clothing, refused to wear a rented cutaway tuxedo, opting instead for his own double-breasted blue pinstripe suit and a flowered tie. They looked like a blissful couple.

But even before their Caribbean honeymoon was over, Betty says, Dan stopped courting her, and she began to feel trapped in the role she’d chosen. “He had the idea that (the wedding) changed everything,” she says. “He let the maids go at the honeymoon house. I was supposed to . . . cook and clean” while he studied.

This was a shock. The third of six children of a successful New York City building contractor, Betty had never lived away from home, and she was accustomed to having a maid. Her mother “ruled the roost,” Betty says, while her father earned enough money to join the local country club, send his brood to private Catholic schools and keep Betty’s and her sisters’ closets full of new Villager dresses.

Now that idyllic life had come to an end. She says that her mother, angry that Dan wouldn’t dress up for the wedding, refused to store any of her belongings and insisted that she move everything into Dan’s tiny medical school dormitory room. As her life went “from bliss to disaster,” Betty says, she threatened to leave him. But she changed her mind when she discovered she was pregnant. (“With all my Catholic upbringing and education to be a ‘wife,’ never was sex or birth control one of the topics,” she says. “Dan being an MDA, I thought he knew what he was doing.”) Before the wedding, she had begun teaching third grade. Now she tried to conceal her pregnancy, working until the day she delivered. In January, 1970, when Kimberly Broderick arrived one month early, the couple was unprepared. Betty’s mother had Saks Fifth Avenue deliver “a few clothing essentials,” and Kim spent her first months sleeping in a dresser drawer.

About this time, Dan decided to get into the emerging medical malpractice field by following his medical studies with law school. He applied to Harvard. Betty backed him completely; she would say later, “I’d vote for being rich any day, wouldn’t you?” But when they moved to Somerville, Mass., a working-class community on the outskirts of Boston, Betty felt isolated. Pregnant for a second time, economically strapped and envious of Dan’s involvement in the world, she again wanted out, she says, but she hung on.

Betty had a second daughter, Lee, and then in 1973, after Dan graduated from Harvard Law School, the Broderick family moved to San Diego. Dan and Betty had been married four years, and during that time, she says, “the balance of power between us had been totally reversed.” “I went from being accomplished, well connected and free to being isolated from family and friends . . . and trapped with two children for whom I was 100% responsible,” she wrote in an unpublished 90-page account of her marriage that she titled “What’s a Nice Girl to Do? A Story of White Collar Domestic Violence in America.” “Dan went from being a student on his own, with no possessions, no savings, no connections or contacts, to being an MD/JD, who had many, many contacts.”

Indeed, Dan seemed to blossom in Southern California. Soon after he began his new job at San Diego’s oldest law firm, Gray, Cary, Ames & Frye, the quick-witted young litigator was recognized as a powerful orator who tempered his ambition with a sense of humor. He specialized in civil litigation, with an emphasis on personal injury and insurance law, and within a few years he would become known as San Diego’s preeminent plaintiff’s lawyer in the field of medical malpractice.

“He had an incredible force that stemmed from personal integrity. It was really unusual,” says Brian D. Monaghan, a lawyer at a competing firm who became a close friend. “Dan had the capability to be President of the United States or a great senator--somebody who could affect many people’s lives.”

Dan and Betty were quickly absorbed into the Gray, Cary social scene--a fast-paced network of attorneys and their mates. Betty, whom Dan referred to as Betts, soon threw herself into being Dan’s partner. During this time, she says, she never paid a bill--she didn’t even have a bank account in her name. Dan took care of the money, she says, and she raised the kids. “If by other people’s definition it wasn’t happy, it was the deal I made,” Betty says. “It was the kind of family we both were from.”

Within a few years, Dan’s income began to ease the family’s financial burdens. By the time Daniel IV was born, in 1976, the Brodericks had bought their first house: a five-bedroom tract home in La Jolla. In 1978, when Dan left Gray, Cary to start his own practice, they had a swimming pool dug in the back yard. A fourth child, Rhett, was born in 1979, and soon, the Brodericks were living very well.

They joined both the La Jolla Country Club and the Fairbanks Ranch Country Club and became members at Warner Springs Ranch, a private resort favored by San Diego’s oldest and wealthiest families. They had a ski condominium in Keystone, Colo., a boat and several cars, including an MG and a Jaguar. The Broderick girls attended the Bishop’s School in La Jolla, and the boys went to the Francis W. Parker School, among the county’s most prestigious private schools. There was plenty of money for summer camps and ski vacations, cruises and trips to Europe.

Betty’s life had finally surpassed what she’d known as a child, but her children say that achievement did not bring the family any peace. “Mom was always kind of weird,” recalls Kim, now 20. “Mom would get mad at Dad all the time. Once Mom picked up the stereo and threw it at him. And she locked him out constantly. He’d come around to my window and whisper, ‘Kim, let me in.’ ”

Betty’s anger wasn’t always reserved for Dan. Kim says it was not uncommon for her mother to throw frozen food or to hit Kim and her headstrong sister, Lee.

“Lee would always say, ‘Your spankings don’t hurt me’--you know, she was bratty,” Kim recalls. “So Mom said, ‘OK, next time you’re bad I’ll hit you with a fly swatter.’ Lee was out in the yard and Mom went after her with the swatter and the little screen came off so it was just the wire and she kept hitting her. Lee had big welts all over her legs. . . . I’d grab Danny and hide in the closet.”

Over a dozen years, Betty threatened to leave Dan a hundred times, Dan’s brother Larry estimates. Dan responded by retreating from Betty and escaping into his work. “He didn’t pay much attention to her,” Larry says. “The more it happened, the more he would tune out.”

Kim concurs: “She was always getting all dressed up and at the last minute saying, ‘I’m not going.’ And she was always telling me they were getting a divorce. She’d say, ‘Who are you going to live with?’ I was dying for Dad to divorce her. I’d say to Dad, ‘Just take me the day you leave.’ ”

Betty says Kim, who now lives near Larry in Colorado, is weak and impressionable. She refers to Larry as Dan’s “detestable” brother and says they have never liked each other. She admits that Dan was increasingly busy and aloof, but she was content. By 1982, she says, her budget was unlimited and all was well.

And then, in September, 1983, Dan hired an assistant, Linda Kolkena. Betty would mark that date as the beginning of the end. And as her marriage dissolved, she says, so did she. “The people who knew me before 1983 knew the real me,” says Betty. “Nineteen eighty-three was like an ax through my life.”

DAN BRODERICK LIKED to be in control. After he went into private practice, he always worked alone. He made his own appointments, carried his own calendar and brought work home each night to keep up with his growing caseload. He didn’t even have his own secretary, choosing to share a receptionist with other lawyers.

But 22-year-old Linda Bernadette Kolkena caught his eye. A former stewardess and paralegal from Salt Lake City, Kolkena was bright, organized and engaging. She hadn’t been to college and she couldn’t type, but just a few months after she became the receptionist on his floor, Dan offered her a job as his legal assistant.

At first, Betty was glad Dan had hired someone. She already felt he spent too little time at home. Then, a month later, on a vacation in New York City, her feeling changed. Betty remembers that, sensing Dan’s distant mood, she had kept the trip low-key, forgoing shopping and sightseeing to accompany Dan on a walk around their old haunts.

“On the walk, he told me he didn’t love me anymore--in fact, he hated me,” she recalls. Suspecting an affair, Betty demanded that he fire Linda. Dan refused, denying that they were involved. A few weeks later, when Dan came home with a new red Corvette, Betty bought books about how to survive a midlife crisis.

“This was just a phase, a bad time--too stupid to be true,” she wrote in her account of the marriage. “That girl had nothing on me. I am prettier, smarter, classier; she is a dumb, uneducated tramp with no background or education or talent. He’ll definitely get over it.”

But on Dan’s 39th birthday, Betty paid a surprise visit to his office and found the remains of a party--champagne, chocolate mousse cake and balloons. Dan and Linda had been gone for most of the day, the receptionist told her. Betty went home, piled Dan’s custom-made clothing in a heap in the back yard and set it on fire as her children watched. When Dan returned, she met him at the door, handed him his checkbook and said, “You’re out of here.”

“I can’t imagine what I could have done, short of shooting him, that would have been a stronger statement than this,” Betty wrote in 1988. But Dan refused to leave. Larry Broderick says that despite the turmoil, his brother’s Catholic upbringing made him unable to give up on the marriage. But Betty says Dan was simply buying time. “Dan transformed himself from a husband to a lawyer plotting strategy in his case,” she says.

In September, 1984, Dan discovered a crack in the foundation of their home that required extensive repairs. The family moved into a large rental house. Betty is convinced that Dan used the repairs as an excuse to get her out of the house.

In February, 1985, three months after his 40th birthday, Dan moved out, returning to the damaged Coral Reef house. He was not involved with Linda, he said; he just wasn’t happy. Desperate, Betty dropped the kids on Dan’s doorstep, one by one. Kim, then 15, was first.

“It was on Easter,” Kim recalls. “I asked her to drive my friend home, and she lost it. She said, ‘Pack your bags.’ ” When Kim arrived at her father’s, no one was home, and she waited hours on the doorstep for Dan to return. In a few days, Danny arrived the same way, followed by Rhett and Lee a month and a half later. “They were hysterical--holding onto her, crying and screaming. Crying hard, ‘Don’t leave us here.’ It was awful,” Kim says. “She said, ‘I’m leaving. Your dad’s not going to get away with this.’ ”

Betty says she wanted Dan to see how difficult parenting could be. And she also held out some hope that by reuniting Dan with his children, the family might stay intact. Soon, however, Betty’s behavior made that impossible.

In June, she went to the Coral Reef house and trashed Dan’s bedroom, shattering mirrors and spray-painting the walls, curtains and a brick fireplace black, according to a declaration Dan later filed. In September, Dan filed for divorce. A month later, Dan said, Betty returned twice to Coral Reef. The first time, he said, she took a cream pie from the kitchen and smeared it all over the master bedroom. Four days later, he said, she threw bottles of wine through two windows and smashed a sliding-glass door.

Dan got a temporary restraining order keeping Betty 100 yards from the house, his car and his office. She promptly violated it, swinging an umbrella through a large picture window and smashing a new toaster. In November, Dan filed criminal contempt charges against Betty.

Things would only get worse. In February, 1986, Dan sold the house, using a little-known procedure that permitted a judge to sign over Betty’s half. Dan claimed he’d appealed to the judge for help only after Betty twice refused to sign the sale papers--even though he had followed her advice in choosing a real estate agent and setting a price and had bought her another home for $650,000 in La Jolla Shores.

Furious about the sale, Betty drove to Dan’s new home. He ordered her off the property. She drove her Chevrolet into Dan’s front door. In court documents, Dan declared that when he opened the car door to pull Betty out, she reached for a large butcher knife under the seat. He restrained her, and she spent three days in the San Diego County Mental Health Hospital in Hillcrest.

Dan and his attorney went to court to make the divorce final in July, 1986. Betty had no lawyer at this point--she claimed she couldn’t find a qualified attorney who would oppose Dan (she would hire and fire five attorneys throughout the extended divorce proceedings). Dan received sole custody of the children with no visitation rights for Betty. To this day, Betty says there was no custody hearing and that Dan and the judge cut a deal behind her back (her claims can neither be supported nor refuted because Dan had the divorce records sealed over Betty’s protests).

Suddenly, Betty says, “I wasn’t Mrs. Anything.” She had a house, a car, a closet full of $8,000 ball gowns and $2,000 outfits. A long-legged, slender 38-year-old, she was receiving $9,036 a month, tax-free, from Dan. She had a teaching credential, a real estate license and plenty of friends. But from then on, Betty says, Dan held “all the cards. . . . That’s a good attorney. Back you into a corner, take all the cards away and then say, ‘We’ll play cards--my way.’ ”

She was determined to defy him. By her own admission, her language was becoming more and more crude. She chose obscene nicknames for Dan and Linda, whom he was openly seeing, and used them in frequent messages on his answering machine. So Dan began to withhold $100 for every obscene word she used, $250 for each time she set foot on his property, $500 for every entry into his house and $1,000 for every time she took one of the children without his permission. In one month, Betty claims, Dan fined her so many times that her allowance totaled “minus $1,300.” A month later, a judge ordered Dan to pay Betty $12,500 a month--a sum that was later increased to $16,100 a month.

Betty claims that Linda “went out of her way to earn the title” that she had chosen for her, but Linda’s friends are incredulous at the charge. When Betty received a photo of Linda and Dan in the mail, as well as an anonymous note--”Eat your heart out, bitch!”--she was sure Linda had sent it. Advertisements for wrinkle cream and weight-loss products arrived in a separate envelope, she says. Worst of all, Betty says, Linda refused to return Betty’s wedding china, even after purchasing new dishes of her own--an action Kim confirms.

Friends say Dan and Linda weren’t capable of the cruelty that Betty alleged. They say Linda changed Dan, softening his often blunt manner and making him smile. A natural comedienne, Linda got laughs from Dan by reciting the airline safety instructions that she’d memorized as a stewardess and coaxing him to act out scenes from Peter Sellers movies. Dan and Linda were too busy enjoying each other, friends say, to spend time tormenting Betty. They were engaged in June, 1988.

Betty, meanwhile, continued to call herself Mrs. Broderick. Diane Black, one of several divorced women who gradually became Betty’s closest friends, says Betty refused to take back her maiden name, despite Black’s belief that it would make it easier to find a lawyer. And Betty once suggested that Black hire Dan to represent her in an insurance matter. “She said, ‘He is the best,’ ” Black recalls. “She was proud. She helped make him.”

But her pride was double-edged. Betty believed Dan was a winner partly because he would stop at nothing to assure victory. By this time, Dan was president of the San Diego Bar Assn. When the court record of their divorce disappeared from the family court clerk’s office in 1987 and then inexplicably appeared again, Betty was certain Dan had reassembled it. Before it was lost, she says, the file had been full of her handwritten notes. After it reappeared, the file was clean. So she “corrected” it again. “In letters four inches tall, I wrote, ‘THIS IS NOT THE FILE,’ ” she recalls.

Betty claims that Dan and Linda were “ruining” her children. As the custody and support battles dragged on, their younger daughter, Lee, dropped out of high school. Dan later disowned her, formally writing her out of his will. He asked Kim to move out when she turned 18, although he later relented, and eventually paid her college tuition. Betty focused her energy on gaining custody of Rhett and Danny. The boys, who are now 11 and 14, gravitated toward their mother. Diane Black recalls that even between informal visits with Betty, the boys stayed in constant telephone contact with their mother.

Betty had a special “kids’ line” installed in her home, carried a cellular phone in her purse and called the boys several times a day. But Dan frequently turned the ringer off on his phone, sending all calls to his answering machine, which sometimes carried Linda’s voice. And Betty responded with dozens of profane and often sexually explicit messages. At one point, Dan wrote to protest the “disgusting and unseemly word” she used to describe Linda. (In the court records, Betty has defaced the letter, writing in the margin, “She is disgusting and unseemly.”)

“I know your first impulse upon reading this letter will be a violent one,” Dan wrote. “You have told the kids that if I withhold any money this month . . . you will kill me and see that not a brick is left standing in my house. You better think twice about that. If you make any attack on me or my property, you will never again get a red cent out of me without a court order.”

Betty was not dissuaded. “I wish I could finish this tale of woe,” she wrote. “I tried to finish it five years ago, when I burnt his clothes and threw him out. . . . If this is the way domestic disputes are settled in the courts, is there any wonder there are so many murders? I am desperate. What is a nice girl to do?”

WHEN DAN AND LINDA were married in his front yard in Marston Hills in April, 1989, Dan hired undercover security guards, but he refused to wear a bullet-proof vest, as Linda requested. He told friends he doubted Betty would kill her “golden goose”--the man who was paying her bills.

Linda wasn’t so sure. On several occasions after the marriage, she asked a divorce lawyer and close friend, Sharon Blanchet, to prepare papers to obtain a restraining order against Betty. Dan wouldn’t let her file them. On other occasions, Larry Broderick recalls, Dan would have Betty jailed, but then would ask the judge to suspend the sentence.

“She was the mother of his children, and he really didn’t take the strong measures he could have taken,” says Ned Huntington, a friend who succeeded Dan as president of the county bar. “He didn’t want the guilt of being punitive toward her. So he let her get away with a lot of atrocious acts. He just wouldn’t punish her.”

Blanchet’s growing concern about the situation prompted her to ask Dan if Betty’s parents could help. She recalls Dan’s reply: They didn’t want to get involved. “They should have come and taken her away and helped her ease her pain,” Blanchet said recently, as tears filled her eyes. “If I ever see her parents, I will go up to them and say, ‘Where were you?’ ”

Frank and Marita Bisceglia live in a modest, two-story gray house in Eastchester, N.Y., just a few miles from the Bronxville home where they raised Betty and her five brothers and sisters. The last time the Bisceglias visited their middle daughter was in 1986, nearly a year after Betty and Dan separated. They cut that visit short when Betty crashed her car into Dan’s door. When the Bisceglias learned their daughter was in a mental hospital, they boarded the next plane home. They haven’t been back.

In February, Betty called her parents and asked them to come to San Diego for her trial. She told them she wanted the jury to know that, even now, her family cares about her. “They wouldn’t come,” she says, her voice hard. “They don’t want anything to do with it. It’s too off their scope of experience.”

A few weeks later, I knocked on the Bisceglias’ front door. Betty’s mother was tall, like her daughter, and as I introduced myself, she looked down at me and listened impassively. She knew I was coming--Betty had called, and I had written a letter--so as she drew in her breath and spoke, I was not surprised that her words sounded rehearsed.

“We are a couple in our mid-70s, and we are hanging on by our fingernails to get through this,” she said flatly. She didn’t open the glass storm door between us. “We have nothing to say.”

When told about our brief meeting, Betty was disappointed but not surprised. “It’s a shame that my mom is like that,” she said. “She cannot face anything that’s not perfect. She doesn’t have that extra what-it-takes to pick up the pieces. Her only way to handle it is to erase it.”

Betty says she was always taught that a good daughter “brings praise to her family, not dishonor.” And for most of Betty’s life, she didn’t disappoint them. Her two sisters started careers--one produces commercials in Los Angeles; the other works in county government in Maryland. But a family friend remembers that Betty was her parents’ “sparkling golden girl.” Betty says they were proud that their daughter had married a doctor. When Dan divorced her, however, her parents abandoned her.

“Their darling daughter got the big D word, and they couldn’t handle it,” she says. “All my life I tried so hard to be a good daughter, a good wife, a good neighbor. . . . My husband unzips his fly and screws the bimbo, and I lose all that.

“My mother is a peach,” Betty says. “If you called home at midnight and you had a flat tire, she’d lie in bed and have people bring her tea and crumpets while she worried about you. And you’d still be out on the freeway. . . .

“What she doesn’t understand is she only had one choice: his funeral or mine. I hate to tell you, she would have preferred mine. ‘My daughter killed herself’ is more acceptable than ‘My daughter stood up for herself.’ ”

THE DAY AFTER the slayings, San Diego County Deputy Medical Examiner Christopher Swalwell concluded that Linda was killed instantly when a bullet penetrated her brain stem. Dan died more slowly, as blood filled his right lung and made it more and more difficult to breathe.

“It took a few minutes, probably,” said Swalwell, whose examination of Dan’s corpse revealed another important detail: a healthy liver. In the months after the murders, Betty had bolstered her description of Dan’s “cruel” side with the claim that he suffered from chronic alcoholism. Now, however, his own body seemed to tell a different story.

“There was nothing that I found that indicated he was a chronic alcohol abuser,” says Swalwell. While not all chronic drinkers have visibly damaged livers, he says, “the more of an alcoholic you are the more likely you are to have damage. His liver looked normal and didn’t show any of the changes associated with alcoholism.”

That was not the only flaw in Betty’s story. Another perplexing part of the puzzle was Bradley T. Wright, 36, a tall, sandy-haired businessman and avid sailor who calls himself Betty’s boyfriend. For months, Betty had told me that Dan had kept a grip on her personal life. “Dan divorced me totally, completely, but I was still married to him because I had no (final) settlement,” she says. “For five years, he had someone to sleep with, party with, have dinner with. I’m standing there going, ‘What about me?’ ”

In fact, Brad and Betty ate dinner and slept together frequently for years. At 7:30 on the morning of the murders, Brad was in bed at Betty’s home when he was awakened by the telephone. Diane Black spoke quickly: Betty had just called and said she had shot at Dan. She had considered committing suicide but ran out of bullets, Black told him. Brad contacted a neighbor--a longtime friend of Dan’s--and together they hurried to Marston Hills, rushed into the bedroom and found the blood-covered bodies.

The memory still haunts Brad, but he has remained devoted to Betty. In recent months, he has managed her affairs--selling her house and putting her furniture in storage. Although Betty’s daughter Lee lives nearby in Pacific Beach, Betty’s mail has been forwarded to Brad’s fence-construction business, and most weekends he drives to the jail to deliver it.

During the four years Betty and Brad knew each other, their lives had become increasingly intertwined. “He did the boy jobs; I did the girl jobs,” Betty says, describing how she kept a list on her refrigerator of tasks she needed Brad to do. The week before the killings, they had returned from a trip to Acapulco, she says, and they often slept in the same bed. Yet she denies Brad’s claim that they were intimate.

“I’m not the kind of person to be with someone and not be married,” she says, noting that Brad is six years her junior. “I never brought Brad anywhere as my date because he was too young. I didn’t want to be the other half of the midlife joke.” When asked why he often slept over, she answers, “It was like having a dog, but he was house trained.”

Kim says she and Lee often confronted their mother about the relationship. Once, after Lee walked in on the couple in the shower, Kim asked her mother how she could be mad that Dan had Linda when she had Brad. Betty replied: “How can you equate the two? Brad doesn’t support me!”

“Mom could never admit that she’d ever have a happy life,” Kim says. “That would be admitting that she could get on with herself and that Dad didn’t ruin her life.” According to Kim, hating Dan and Linda became Betty’s reason for living. And she punished those who didn’t share her feelings. In August, 1988, when Kim was 18 and discovered she was pregnant, she turned to Linda for help in getting an abortion. When Betty found out, Kim says, “she sent a letter to my dad’s whole family and called one of my friend’s mothers. Whenever friends came to the house, she talked about it. The whole world knew.”

Betty herself had gotten an abortion--against Dan’s wishes--when Kim was 4 and Lee was 2 and she “needed to come up for air.” Fifteen years later, however, she made a public example of Kim--to punish her, Kim believes, for relying on Linda.

Dan’s friends say this kind of vindictiveness was common. According to a story Linda often repeated, Betty told Rhett that if he loved her, he would stab Linda in the stomach. On other occasions, friends say, Betty told her sons that when Dan and Linda had a baby, as they were planning, Dan would no longer be their father.

Betty denied these charges to me. But at her preliminary hearing, Kim testified that her mother’s cruelty was frequently aimed at her children. Often, Kim testified, Betty told them she hated them.

Betty dismisses her outbursts as the fury of a protective mother--a “mommy tree protecting the little saplings.” She wanted to be known as a selfless woman, a martyr who was willing to face prison in order to free her children from a man who “would not relinquish power.” But again, there is a flaw in her argument. Kathi Cuffaro, an associate of Dan’s who was handling his divorce settlement at the time of the murders, says Dan had told Betty he would give her what she said she wanted most: custody of Danny and Rhett.

Dan’s offer had stipulations: He wanted Betty to have the boys on a trial basis, and he wanted an “automatic revert” clause written in to any agreement so that he wouldn’t have to return to court if things didn’t work out. But Cuffaro says Dan “was convinced he needed to try it to see if that would calm her down.”

Betty says Dan was bluffing. Two days before the murders, when she received the legal papers at her door, Betty says she decided “he was never going to let me have those kids.”

But Sharon Blanchet believes Dan had made himself clear. If the boys came to stay, she says, Betty knew she would lose her excuse to intervene in Dan’s life. “She was a woman who used her children to her purpose, and her purpose was to make life as miserable for Dan as she possibly could,” Blanchet says. “She killed him because there wasn’t going to be anything more to argue with him about.”

FIVE DAYS AFTER the murders, more than 600 people, many of them lawyers and judges, crowded into St. Joseph’s Cathedral for a memorial service. Dan’s and Linda’s matching wooden coffins were crowned with roses--red for his, white for hers.

For some of the mourners, grief soon hardened into anger. “This was a cold, calculated execution,” Larry Broderick told me later. “Anybody who thinks it was anything different than that is wrong. She’s playing everybody like a goddamned fiddle.”

Betty, who has pleaded not guilty and is being held without bail, continues to maintain that she cannot get a fair trial in San Diego County. She notes that several of Dan’s former associates, including a lawyer who represented him in their divorce, are now judges. “Even though my husband is gone, his friends are still here,” she wrote in a letter from jail. “If anything, my husband’s influence in legal circles has grown.”

Jack M. Earley, the third lawyer she has retained since the killings, says he has not ruled out the insanity defense. No matter what, he says, his case will hinge on how well he paints a portrait of “what got her to the point that she got to”--a process that will rely heavily on the testimony of several lawyers and judges who were involved in the Broderick divorce. For that reason, Earley filed a motion to disqualify the entire San Diego bench. When it was denied last month, he said he would likely challenge each of the 69 Superior Court judges one by one.

Betty’s trial is now scheduled for September. Deputy Dist. Atty. Kerry Wells says she will seek a life sentence without the possibility of parole--not the death penalty--because all four children are likely to be witnesses in the case. “Putting them in the position of having to play a part in perhaps losing their mother to the gas chamber is just too much,” Wells says.

Betty, meanwhile, remains defiant. Kim says she calls frequently to check on the boys, who are living in Colorado. Recently, Kim says, Betty told her to “kidnap Danny and Rhett and groom them and raise them in San Diego. She still thinks she’s going to get out.”

And she continues to describe her actions as self-defense. “The only thing I was doing that morning was making it stop,” she says. “My lawyers hate it, because there’s no law that says I can defend myself against his type of onslaught. He was killing me--he and she were still doing it--in secret.

“It always makes me mad when people call them the victims. Me and my kids were the victims. There are two dead people, but there were five victims,” she says.

In one of our last conversations, Betty said that since the murders, she has warned her daughters never to depend on men. “That makes me so sad, because I really believed in my little fairy tale,” she said, crying into the phone. “I would love them to find husbands to provide for them. But I can’t tell my daughters to buy into that anymore. It’s too dangerous. Look at what happened.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.