L.A. plans to plant 90,000 trees in two years. What can we learn from its oldest trees?

- Share via

Rachel Malarich faces a pressing task: overseeing the planting of 90,000 trees over the next two years in Los Angeles, home to the largest urban forest in the United States. As the city’s first forest officer, the veteran arborist needs to boost the tree canopy by at least 50% in shade-starved low-income areas by 2028. “The goal is ambitious,” she said. “But through the collaboration of city departments, nonprofits and local communities, we can make it happen.”

Mayor Eric Garcetti, who appointed Malarich to the post in August, said at the kickoff of what’s called L.A.’s Green New Deal, which expands the city’s 2015 Sustainable City Plan: “Trees cool the air, produce oxygen and eat carbon dioxide. Planting trees is the simplest way to combat climate change.” Residents receive a bonus of free trees for their yards and neighborhood streets.

The question at the top of Malarich’s mind right now is which trees to plant in a time of rising temperatures. To find inspiration, she recently took a stroll into the past to visit the city’s first arboretum in Elysian Park, not far from City Hall.

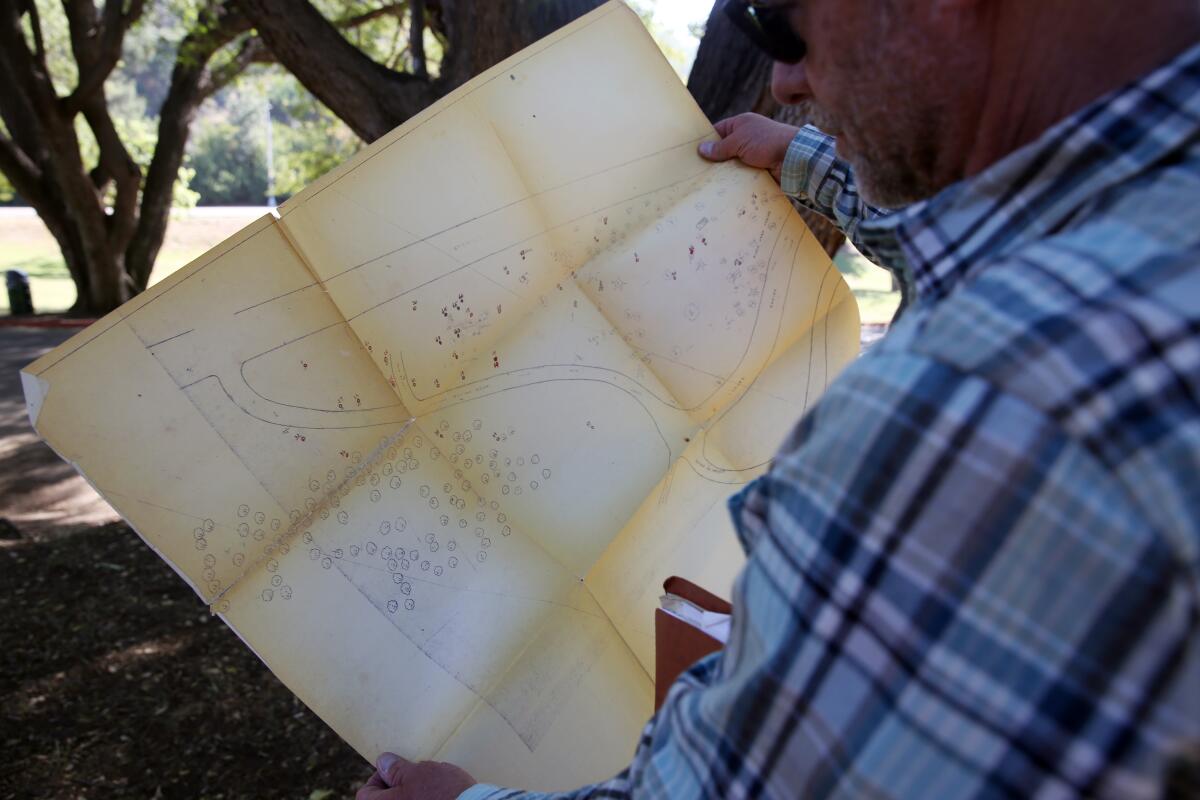

“The arboretum is small, but it has some of the oldest, finest, first or only tree specimens of their kind in Los Angeles,” says L.A. Recreation and Parks tree surgeon supervisor Leon Boroditsky. “We’ve designated many of them as ‘heritage trees.’ ”

Malarich, a native of San Jose who graduated from Cal State Long Beach in 2005, spent over a decade with TreePeople. As its director of forestry for more than three years, she organized volunteer efforts to plant and care for trees in local communities.

Now she’ll do the same for L.A. on a grander scale. She visited the grove of the city’s older planted trees, which covers a few acres in Elysian Park, best known as the home of Dodger Stadium. More than a century ago, L.A.’s more affluent residents in the Horticultural Society of Southern California needed a place to show off their private collections of exotic trees. In 1893, they petitioned park commissioners and the City Council to secure 10 acres of land in the park and paid to pipe in water.

The Los Angeles Times endorsed the plan at the time. “There is no other park in the country which has such magnificent views, or possesses a climate where the most delicate plants will flourish all winter in the open air,” the newspaper announced on Aug. 22, 1893. Planting in what was called the Elysian Park Arboretum began in December.

“The founders planted [tree] species from different parts of the world to see what would flourish in L.A.’s. climate,” says Long Beach City College horticulture professor Jorge Ochoa. “Those that thrived were later planted on streets and in parks throughout the city.”

Malarich hopes to garner similar information from the current inventory she is supervising of every tree on L.A.’s streets and in all of its 464 parks. “It will give us data about what species we have and which are doing well. Hard data is necessary for us to succeed.”

Malarich, Ochoa and Boroditsky all participated in the city’s tree-planting efforts during Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s Million Trees L.A. initiative between 2006 and 2013. The plan fell short of its ambitions, with just about 400,000 trees being planted. It was funded by grants, not taxpayer dollars, and focused on tree-poor areas in South L.A. and the northeast San Fernando Valley.

“Our goal is more realistic,” Malarich says. “Plus we have robust support from city and state funding and nonprofit grants.”

At the old arboretum, Boroditsky points out two graceful old trees, a Cape chestnut from South Africa and a Moreton Bay chestnut from Australia. “These specimens date back to the 19th century, and they’re still doing well,” he said.

Though spotty, records indicate the arboretum included more than 50 species of trees in the 1920s and that more trees — including a cork oak, a river birch and a small grove of California redwoods — were planted during the following few decades. In 1958, however, Dodger Stadium took a huge bite out of Elysian Park, and the city slashed through the arboretum to build Stadium Way. The six-lane road connected the 5 Freeway and the ballpark, but many arboretum trees were sacrificed.

In 1965 developers introduced plans for a convention center adjoining Dodger Stadium. Nearby residents created a grass-roots organization to fight it. The Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park not only blocked the convention center but later won battles against a proposed airport, condominiums, oil wells and zip lines. Thanks to the group’s efforts, the arboretum, renamed the Chavez Ravine Arboretum, was declared Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 48 in 1967.

Since then, the committee has continued to stave off development in the park and encourage the planting of more rare and unusual trees in the arboretum, in keeping with its founders’ intentions.

“The arboretum has roughly 135 different species now,” Boroditsky said. “This planting season we’re adding some new ones, including oaks from Arizona, Texas and Mexico that thrive in hotter climates.”

“Usually I look at trees in urban areas, where they must be pruned to accommodate overhead wires and they have to fight the sidewalk for space,” Malarich said. “It’s a pleasure to see trees here.” She cranes her neck to glimpse the top of perhaps the tallest tree in the arboretum, a Queensland kauri pine. “It makes you realize how immense and majestic these species can get when they have lots of space.”

At one point, she joined Boroditsky and Ochoa under a giant South American tipu tree with a broad, sweeping canopy. “You should see this beauty in the summer when it blossoms,” Ochoa said. “The ground under it looks like it’s covered with a golden blanket.”

Malarich sized up the tree. “It’s way too big for a street tree, but I’d love to see it planted in more parks,” she said. “Standing under a tree like this reminds you that living things this magnificent don’t happen overnight. It requires a long-term investment and commitment to nurture them so they can mature to this age.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.