Tenants worry as Caltrans prepares to sell homes along 710 Freeway corridor

- Share via

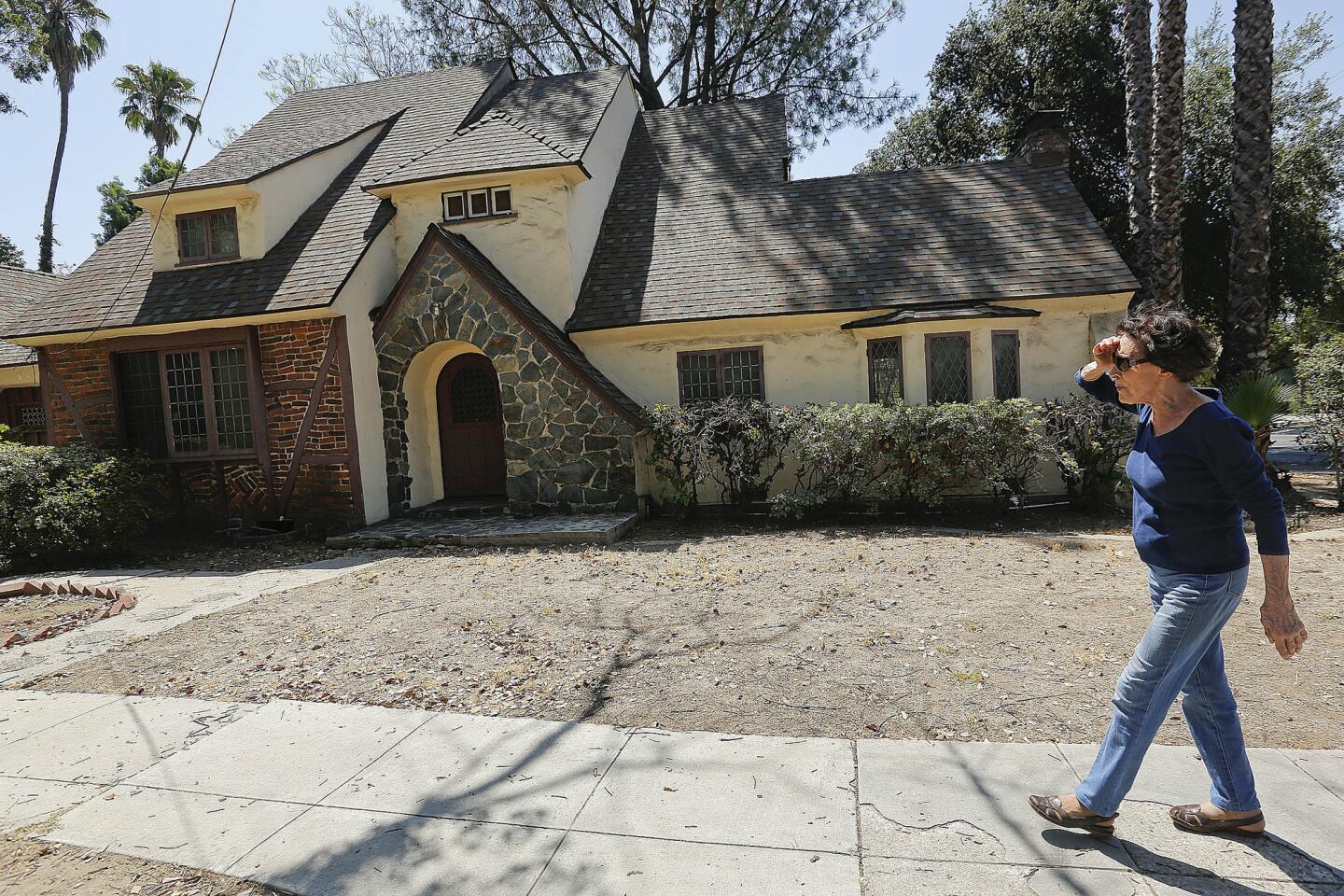

The modest cottages and majestic Craftsman homes that line a swath of quiet streets stretching through Pasadena, South Pasadena and El Sereno are part of the long, tortured legacy of a freeway that was never built.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Caltrans began buying up houses and plots of land for what was expected to be the path of the 710 Freeway extension. But in the decades that followed, the 6.2-mile project was stalled by lobbying, lawsuits and legislation.

Earlier this year, closing the door on one portion of the long-fought battle, officials decided that if anything is to be built to close the transportation network gap from El Sereno to the 210 Freeway in Pasadena, it will be underground. Those options include a light-rail line, a bus rapid-transit system or a freeway tunnel. The final decision is expected next year.

The land occupied by many of the state’s 460 properties along the corridor will no longer be needed. Caltrans has made slow progress this summer in preparing to sell some of those homes — many occupied, and some on the National Register of Historic Places. Officials say if the state approves the sale regulations quickly, most of the homes could go on the market as soon as January, and some sooner.

The news has brought relief for city officials in Pasadena and South Pasadena who’ve spent years railing against what they call poor, and sometimes negligent, property management by a bureaucracy that never should have been a major landlord. But some longtime tenants have also begun to worry that Southern California’s robust real estate market may price them out of homes they have lived in for decades.

Many tenants have tolerated “a distant, potentially unresponsive landlord” because they hoped to get a chance to buy the property someday, said Christopher Sutton, a Pasadena attorney who represents a group of Caltrans tenants. “People put up with a lot, because this is home,” he said.

One of those tenants is Linda Krausen. In 1993, she moved into a cottage on a quiet South Pasadena street that runs parallel to the 110 Freeway . Caltrans had bought the home in the early 1970s for $21,100, expecting the deep lot to be cleared for an interchange between the 110 and 710 freeways.

The 1909 two-bedroom looks a little dumpy from the outside, Krausen said, and has some “nagging issues” that Caltrans hasn’t addressed, including asbestos underneath the flooring in one bedroom. But, she said, it also has promise: a patio and a deep backyard that would be nice if all the asphalt were removed.

Her home will be one of the first to be sold. The sale could happen by November, Caltrans has said.

Krausen, 74, hopes to retire soon from her job as an interpreter at the Los Angeles County Superior Court. She hasn’t seen a cost estimate yet but fears she won’t be able to afford to buy the house on a modest retirement income. Other houses nearby have recently sold for more than $800,000.

“I’ve been very happy here,” Krausen said. “I just want to know if I will be able to stay.”

A document prepared by Caltrans earlier this year suggested that dozens of tenants could be priced out. Under a 1979 law, low-income renters will receive a discounted rate, as could tenants who make less than 150% of the county’s median income: $45,350 for a single person, or $64,800 for a family of four.

“These are people who will struggle to buy their homes because they are too much in the middle class,” Sutton said. “People who are rich enough can pay market value. People who are poor enough will qualify under the affordable sales program. But someone living alone obviously can’t buy a house if the fair-market value is $500,000.”

Former owners and current tenants receiving a reduced rate would have the first chance to buy the property. The next turn would go to affordable housing development companies, then to tenants who would pay market price, then to former tenants in reverse order of occupancy. The final option would be a public auction.

Whispers of impending sales are welcome news for Pasadena and South Pasadena officials, who have railed against Caltrans’ property management for years. Some of the homes for sale line stately streets in the cities’ nicest neighborhoods, including Pasadena Avenue.

“The stance we’ve taken historically has been, ‘Get on with it,’” said Terry Tornek, the mayor of Pasadena. The city has tried several times to “spring” houses in historic districts after residents and preservationists raised concerns about whether they were being properly cared for. “The uncertainty, and the decline of these buildings, it’s just infuriating.”

More than 35 Caltrans-owned homes are considered uninhabitable, according to agency data, and residents have complained of break-ins, mold and vermin infestations. The Times reported in 2011 that roofing bills for Caltrans properties averaged $71,000 each, well above private-sector costs.

A state audit the following year found that Caltrans spent $22.5 million over four years on maintenance it could not justify as “necessary, reasonable or cost-effective.” It also said the agency was losing $22 million per year because tenants, including 15 state employees, were paying far below market rates for rent.

Yolande Treuscorff, 88, of Pasadena, has watched the house next door deteriorate in the 12 years it’s been unoccupied. She’s called Caltrans to report seeing light from flashlights inside, and worries that the house will be difficult to sell because it needs so much work.

The house, on Pasadena’s State Street, bookends a long block of Caltrans-owned Craftsman-style homes with tidy landscaping. On a recent weekday, the house sported several cracked windowpanes, a pile of dried brush in the small courtyard and a slightly neglected air.

The real estate website Zillow estimates the home would sell for at least $1 million at fair-market rates. “And it would need so much work to get it back to where it should be,” Treuscorff said. “It’s really tragic.”

On a handful of blocks in the El Sereno neighborhood of Los Angeles, almost every home belongs to Caltrans. Some tenants, such as Jennie Montoya, 74, have lived there for decades. In 1983, she moved into a modest bungalow on a street less than a mile north of the 710’s abrupt end on Valley Boulevard.

Montoya’s son does most of the small repairs himself, she said, including fixing the plumbing. She and her husband hope they can buy the home, but don’t know yet how much it will cost, or whether they would qualify for an affordable housing discount.

“We like it here,” Montoya said. “But we don’t know what will happen.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.