Column: A new California gold rush for homeowners, the poorhouse for renters

- Share via

I lived in an apartment until I was 8, when my parents scraped together a down payment and bought a modest little house on a cul-de-sac, taking hold of a deed that was our ticket to the kingdom of suburban California royalty.

Housing developments grew out of the dust all around us in eastern Contra Costa County, as working folks took out mortgages on their own sense of pride and belonging.

People extolled the benefits of owning, rather than giving money to the landlord. But in that time, you bought for the sake of inserting yourself into a dream decorated with shaded patios and manicured lawns, and not so much as an investment.

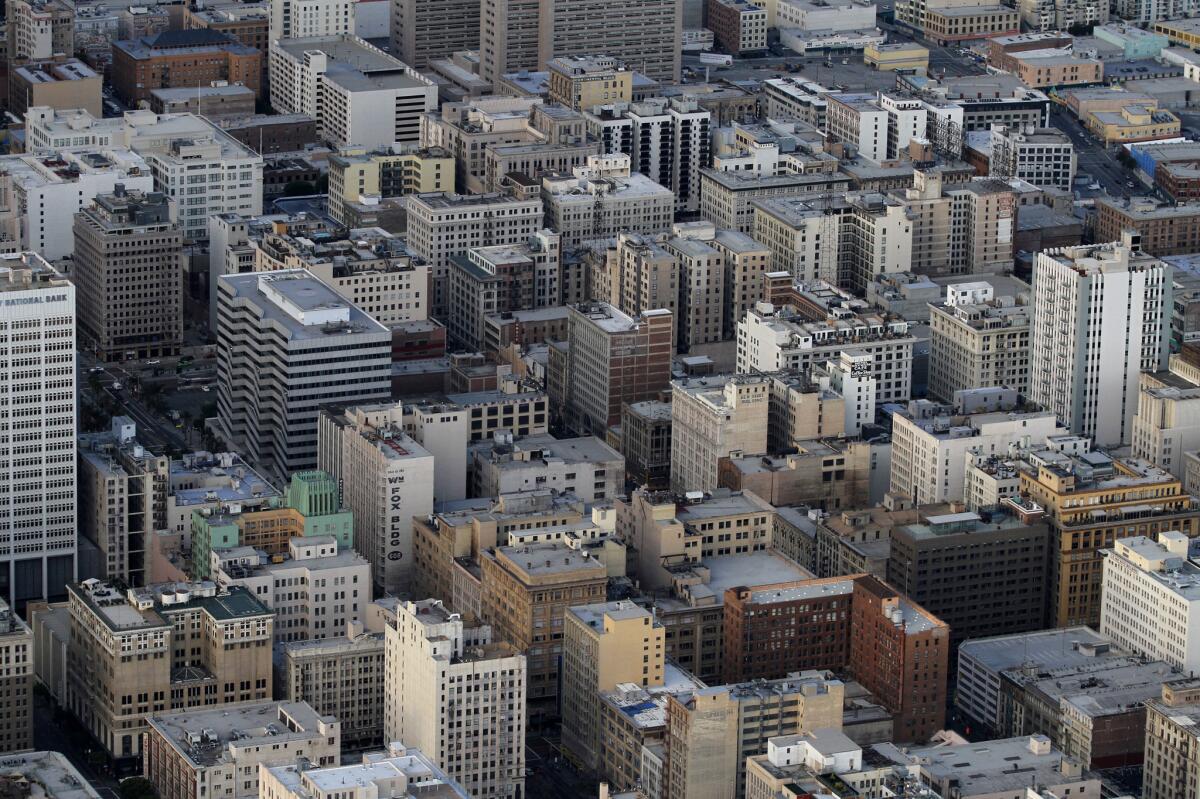

Today, home ownership in California is the best investment any of us will ever make, thanks, in large part, to a scarcity of housing. The pace of construction has not kept up with population grown and demand, so those of us with houses own a staggering amount of equity wealth that grows even as those without homes pay a higher price for survival.

For homeowners, a new California gold rush

California was always a model of stark contrasts in the realm of haves and have-nots. But as rents rise and wages stagnate, a majority of L.A.-area renters are paying more than one-third of their income on rent while thousands are paying 50% or more, with no end to these trends in sight.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of homeowners in Los Angeles and Orange counties have enjoyed super-low interest rates and seen their equity rise to all-time highs. Roughly one decade after thousands of people lost their homes in the housing crash, 96.4% of Californians with mortgages owe less than their homes are worth.

In Los Angeles and Orange counties, 533,000 homes are owned free and clear, and the value of them is $402 billion. That works out to about $700,000 in equity for each owner.

Those who hold current mortgages in the two counties have $842 billion in equity wealth, lifting the two-county equity total to $1.2 trillion.

“A lot of moola,” said Frank Nothaft, who compiled the numbers and is chief economist at CoreLogic, which does global real estate market research. Californians with active mortgages, Nothaft said, have more than one-quarter of the nation’s $8.2 trillion in equity.

Well, good for us, right? By clever planning or dumb luck — and it’s mostly the latter in my case — we are modern-day prospectors in another great California gold rush.

The gains are rightfully owned, and people who have worked and paid their bills and built up a nice cushion for their retirement have no reason to apologize.

Owning a house is a big class divider

But the state with the fifth-largest economy in the world has the highest poverty rate — about 20% — when housing prices are factored into the cost of living.

So here’s a question:

Unless we’re living in a real estate bubble that’s about to burst, which is certainly possible, do those who have prospered owe anything to those who have fallen further behind, including teachers, nurses, laborers and others essential to both our economy and our best definition of community?

It’s easy to say no.

People make their own choices, right? And when homeowners pay property taxes, they’re contributing to the greater good.

But that’s a convenient deception.

Federal and local laws have been rigged for decades to promote home ownership and benefit homeowners, arguably at the expense of everyone else. A prime example is the mortgage interest tax deduction that many in Washington and the real estate industry are fighting to keep.

The system helps those with property, hurts those without

Another is California’s Proposition 13, which gave a much-needed break to homeowners when property values were spiking too quickly, but over-did the benefit, drained communities of vital funding and created a system in which homeowners pay vastly different taxes on homes of the same value.

And then there are all the restrictive zoning policies and homeowner opposition to new construction.

“When we collectively decide not to build housing even as our economy grows, we deliver a windfall to people lucky enough to own homes and a punishment to those who rent,” said Michael Manville, a professor of urban planning at UCLA.

Manville argues that calls for rent control and fees on developers, for the sake of subsidizing a small amount of affordable housing, can have the opposite of the intended goal of more housing and lower prices. (I agree in theory, but would argue there has to be some way to protect people getting whacked by rent hikes of 20% and more).

“If you own a home,” said Manville, “and its value is skyrocketing through nothing you have done, you are in fact a part of the problem, and it is not up to someone else to solve it. You, too, are your neighbor’s keeper.”

A fair way to look after your neighbor, he argues, is by paying a parcel tax that would finance more affordable housing. But that’s a political long shot, partly because homeowners’ equity is on paper and not in their pockets. So Manville suggests a modest tax on the equity at the time of sale and using it to make a significant dent in the statewide housing crisis.

The Legislature passed a much less ambitious version of that idea this year. But a tax of $75 to $225 for refinancing and other kinds of residential and commercial real estate transactions — along with several other modest housing production bills — will add an estimated 14,000 housing units a year to a state than needs 185,000 annually.

So thanks, Sacramento, but when will you really get to work?

There is no one remedy for the housing shortage and rising costs, said Carol Galante of U.C. Berkeley’s Terner Center for Innovative Housing, and I agree. She suggests a tax break for landlords who rent to low-income people, lower construction costs for developers through infrastructure investment and other means, low-cost modular apartment construction and the incubation of more political courage.

“It’s not going to get any better unless we touch some political third rails,” Galante said. She mentioned tackling Proposition 13’s inequities and promoting a tiered transfer tax on equity that exists because of housing scarcity.

Our kids will pay the price

One way to sell the latter idea politically might be to link equity taxes to so-called workforce housing. In a just society, shouldn’t your kids’ teacher be able to afford a decent apartment or home that’s less than an hour from school?

Los Angeles resident Bobby Turner, of Turner Impact Capital, acquires and manages workforce housing in several other states, offering rent breaks to teachers, nurses, cops, healthcare workers and others who provide an after-hours service in their specialty at the apartment complex.

But he doesn’t do such projects in California, he said, because land is too expensive and it can take years and hundreds of thousands of dollars to go through the Byzantine review and permit process.

Local officials need to clear the way, and state officials need to muster the courage to treat the housing crisis like the calamity it is. Too many working people are playing Sophie’s choice with food and rent bills, neighborhoods are becoming more segregated and working folks are wasting precious hours on long commutes.

My readers often argue that people and companies who can’t afford to live and do business in expensive coastal areas should move east or out of state, and that’s good advice in some cases.

But booming coastal economies could not function without plumbers, janitors, police officers, landscapers, nannies, supermarket clerks, lifeguards, waiters and medical assistants.

California doesn’t have to be a place in which they hustle and sweat but never catch up, as those of us with mortgages earn money while we sleep.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.