Law gives social workers access to foster parents’ criminal records

- Share via

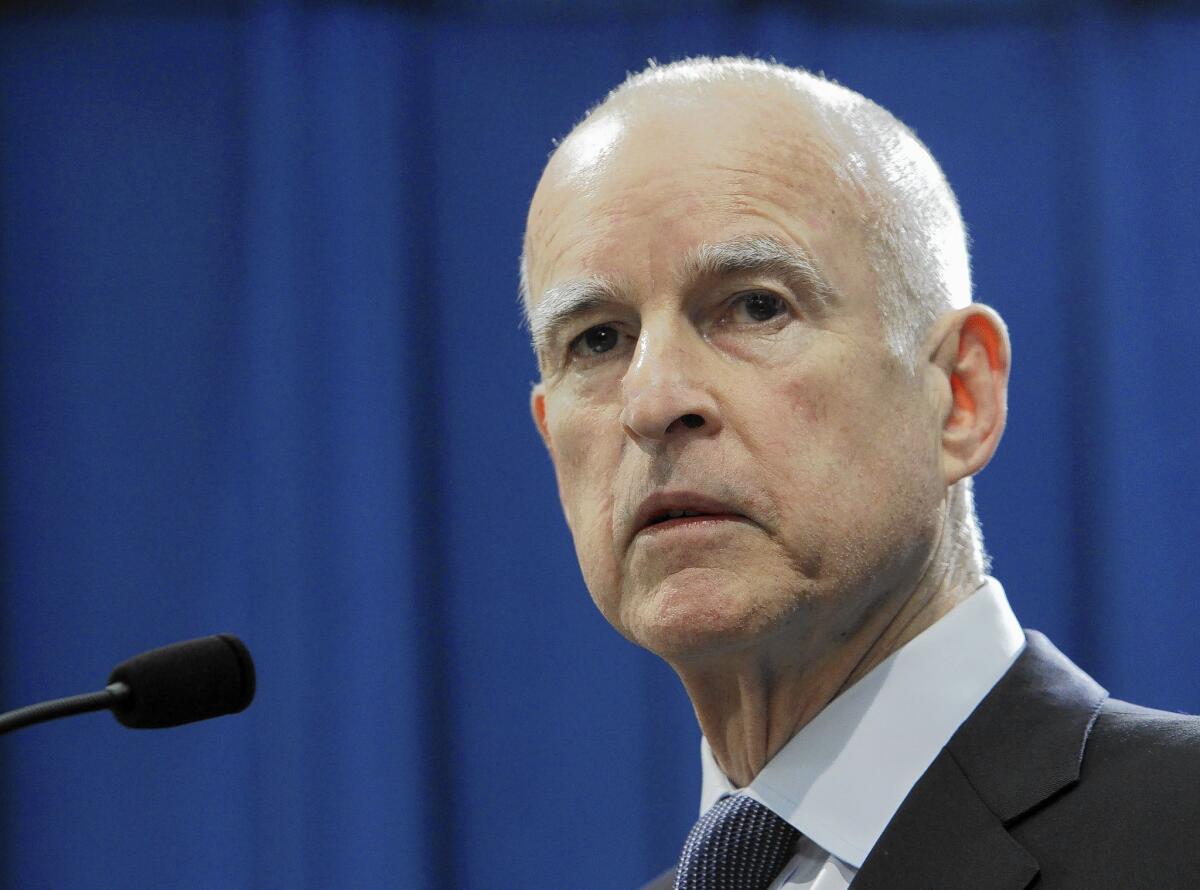

In response to a series of scandals involving mistreatment of children under state supervision, Gov. Jerry Brown on Thursday signed into law new rules giving county social workers access to the criminal histories of foster parents and employees at foster care contractors before abused and neglected children are placed in their care.

The legislation, SB 1136, comes in response to Times reports documenting instances when children were harmed and taxpayer money was allegedly misspent by people with criminal backgrounds who had been granted special waivers from the state to receive foster children. In the past, county social workers, who have the responsibility to place at-risk children in safe homes, were unable to view criminal records of foster parents or workers at agencies that help find and train foster families. The law takes effect Jan. 1.

Over the past year, The Times has reported on a convicted forger who auditors said mishandled tens of thousands of taxpayer dollars as a chief executive of a private, nonprofit foster care agency; a convicted thief who later was found guilty of murdering a foster child; and a woman convicted of fraud who was later convicted of criminal charges for causing debilitating burns to a girl in her care. Each had received a special waiver from the California Department of Social Services to enter the foster care system.

The state has granted more than 5,000 waivers currently in effect; 1,400 of them in Los Angeles County.

“We should allow state and local agencies to work together and share information to protect innocent children from additional harm or danger. Our legislation will allow this,” said Sen. Bob Huff (R-Diamond Bar), who cosponsored the law with Sen. Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles).

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors sought the legislation earlier this year.

“It is possible for government to better protect children while cutting red tape. Today our colleagues have agreed that this is the right approach,” Mitchell said.

The Times also has reported that county workers had no reliable means to ensure that social workers at nonprofit, contracted agencies that recruit and supervise foster parents were complying with rules limiting them to oversight of 15 foster children at a time. The paper found that numerous private social workers violated the cap while supervising children who were injured by their foster parents, according to records filed with the state.

Some social workers got around the limit by working for multiple foster care agencies. L.A. County officials have sought to crack down on the practice by requiring foster care agencies to submit information on their social workers’ outside employment.

Additionally, state and county workers are imposing new requirements on nonprofit foster care organizations to obtain advance permission before entering into business and real estate transactions with their employees.

State records show that between 2007 and 2011, one foster care agency executive, Sukhwinder Singh, charged the taxpayer-subsidized organization she managed almost $1.8 million in rent for properties she owned. Auditors found that some lease payments for the properties were significantly higher than allowed market rates and totaled thousands of dollars in impermissible payments.

Other efforts to improve the state’s contracted-out foster care system, which oversees 15,000 children, have stalled.

Some county officials and advocacy groups have called on the state to change the way it funds nonprofit foster care groups. Critics say the current system encourages the agencies to cut corners and retain children in foster care, and should be replaced with a “performance-based contracting” program. Under that system, agencies are rewarded when they serve children well and penalized when children in their care are abused or fail to make adequate progress developmentally.

Brown’s social services director, Will Lightbourne, said such a major realignment of financial incentives would be too difficult.

Private agencies now care for 15,000 children statewide. They were paid hundreds of millions of dollars more than the government-run system they replaced and were meant to provide children with more intensive services and supervision.

But a Times analysis found children in homes overseen by private, nonprofit agencies were about a third more likely to be victims of serious physical, emotional or sexual abuse than those in state-supervised foster family homes.

Follow @gtherolf for breaking news about the foster care system.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.