Great Read: Finally, a gravestone for little Viola Vanclief

- Share via

For four years, the little girl lay in an unmarked grave beneath the low hum of high-voltage lines — a buzzing lullaby.

No one walking on the browning grass next to the drainage ditch would have known about the toddler buried beneath their feet.

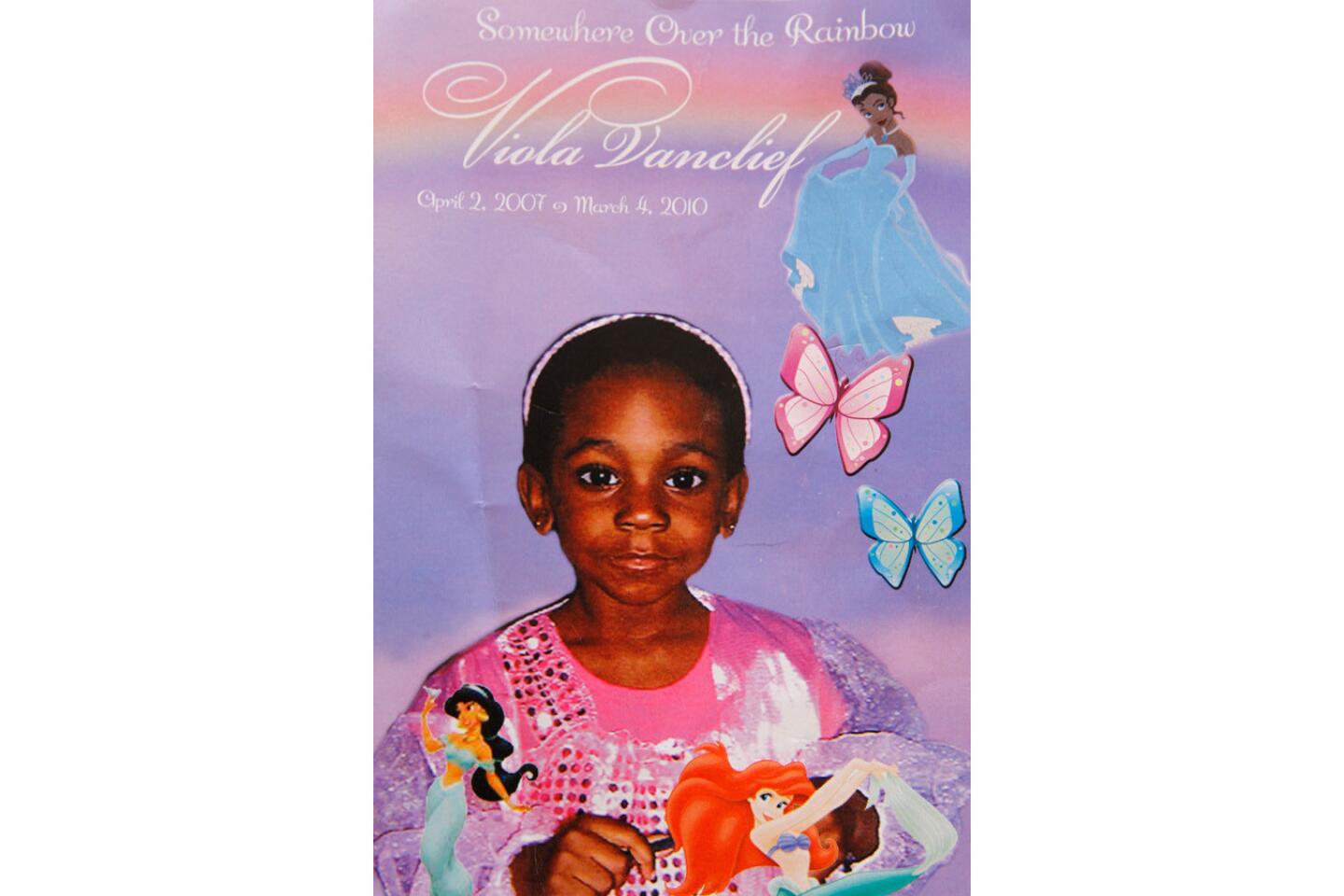

They wouldn’t have known that her funeral program was decorated with Disney characters: Princess Jasmine from “Aladdin” and Princess Tiana from “The Princess and the Frog.” Or that it said she had been “loved by all who met her.”

They wouldn’t have known that she died a month before her 3rd birthday.

They wouldn’t have known that her name was Viola Vanclief.

Los Angeles County social workers knew this about Viola: The almond-eyed girl flinched when an adult raised a hand to wave or to grab something near her.

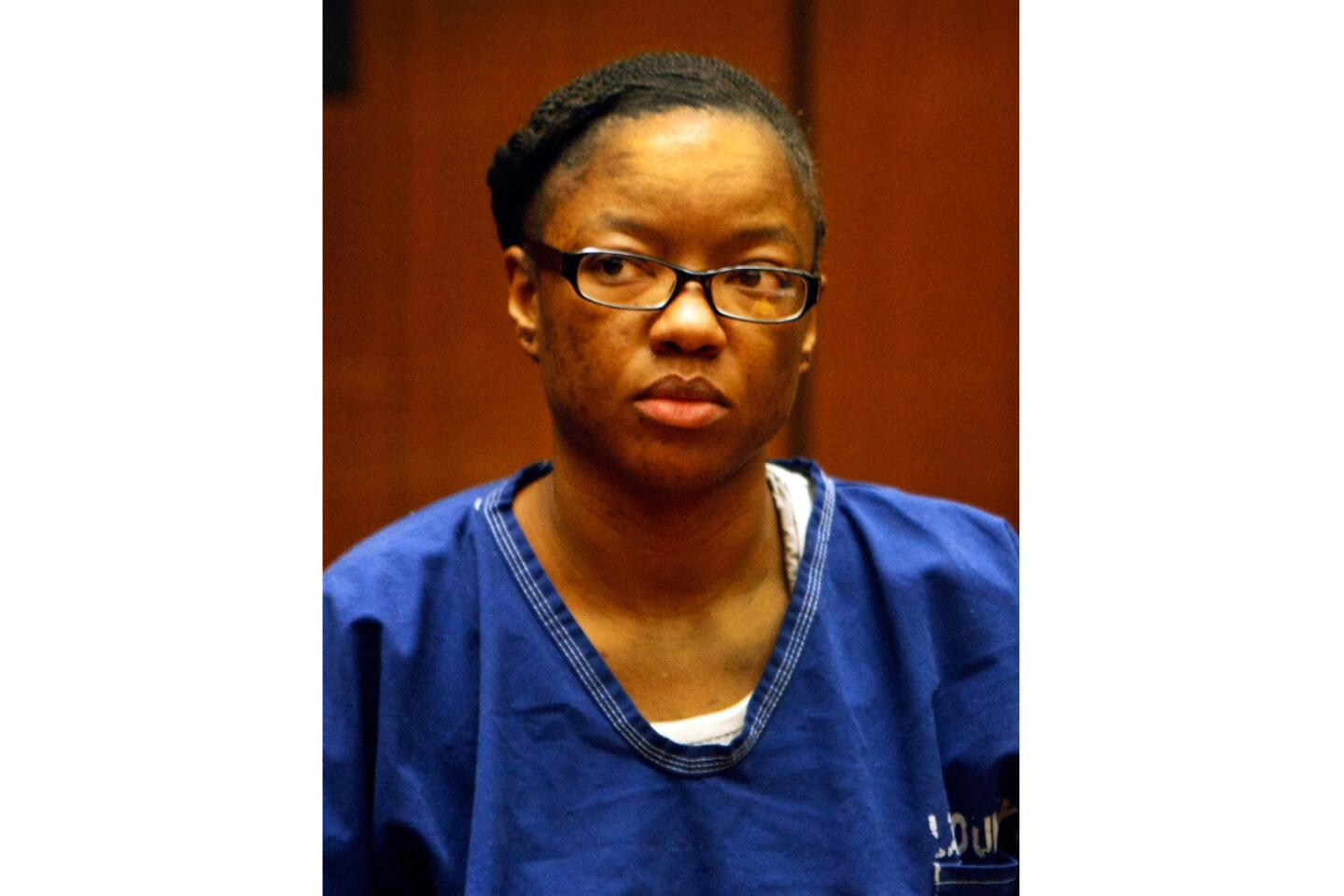

State foster care licensing workers knew that the foster mother social workers had selected to care for her, Kiana Barker, was a convicted robber with a history of violent outbursts.

On March 4, 2010, Barker beat Viola to death. A jury later convicted her of second-degree murder.

After Viola died, a modest service was held at a South Los Angeles mortuary. “Children are a heritage of the Lord; and the fruit of the womb is his reward,” read a biblical verse in the funeral program. A small group of mourners — Viola’s mother, relatives and county workers — then gathered at Lincoln Memorial Park in Carson for the burial.

And then, in death as in life, Viola Vanclief was overlooked, lost in the gap between the limitations of her parents and the state child welfare system that sought to substitute for them.

Her father had not been in her life. Her mother, a crack addict and prostitute, managed to scrape together enough money for the funeral but not the marker. And county social workers didn’t provide one because they thought the family had done so.

Soon, the absence was forgotten, and the grass grew and then withered over the ground where Viola lay, a blank space between the graves for a 77-year-old woman and a child who died on the same day she was born.

::

A sign reading “Sacred Grounds” greets visitors to Lincoln Memorial Park, as well as a bronze bust of Abraham Lincoln and his proposition that “all men are created equal.”

The great jazz pianist Hampton Hawes is buried here, as is Willa Pearl Curtis, who played Buckwheat’s mother in the “Our Gang” movies. The boxing champion Joe Louis visited in 1949 to dedicate a memorial to World War II veterans and their “immortal glory.”

In recent times, the cemetery’s corrugated fence began to sag, a stray chicken made its home amid the graves and groundskeepers learned to take long lunches on the days gang members are laid to rest. Shootings sometimes break out.

Last December, Matty Nierenberg, a 43-year-old Westside investment banker, sat down at his desk and read a story in the Los Angeles Times about foster care. The article mentioned Viola’s case, and that she had no gravestone.

“It was like squeezing the brakes on a bicycle,” he said. “It really stopped me in my tracks.”

He folded the newspaper, took it home and placed it next to his bed, where it remains.

A few days after the article was published, still thinking about the case, Nierenberg sat down and sent an email to the Department of Children and Family Services. Could he pay for a gravestone?

“I think we all sometimes insulate ourselves from things like this,” he said. “But I had just lost my mom, and I knew what was supposed to go into a funeral.”

The county got back with a price, $491.50. Nierenberg wrote a check.

“It just means a few less dinners out or one less surfboard,” he said. “I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth. I didn’t have to worry about being beaten.”

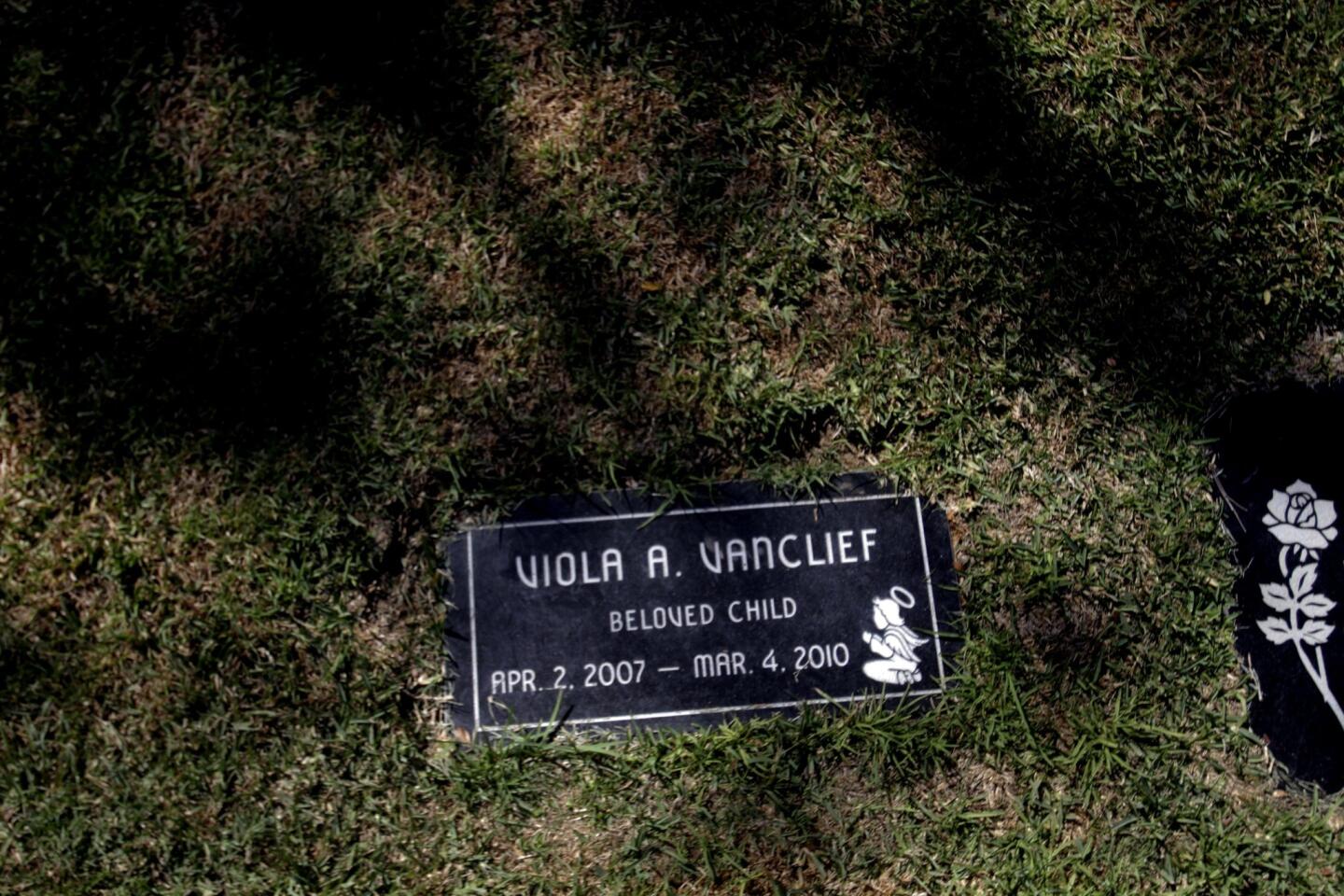

In July, the stone was quietly placed over Viola’s grave, near other children’s markers decorated with Minnie Mouse balloons and pinwheels. Made of polished dark granite, the marker features the image of a young angel kneeling in prayer.

The stone includes Viola’s full name, “Viola A. Vanclief,” and dates that are painful to read: April 2, 2007, to March 4, 2010. Nierenberg and county workers agreed on an inscription: “Beloved Child.”

About 10 feet away lies another 2-year-old girl, Erica Johnson, who was buried months after Viola.

Erica, too, was beaten to death after coming under the oversight of county social workers. Her stone has the same image of the little kneeling angel.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.