Under new rules, Muslim inmates in L.A. County jails observe Ramadan

- Share via

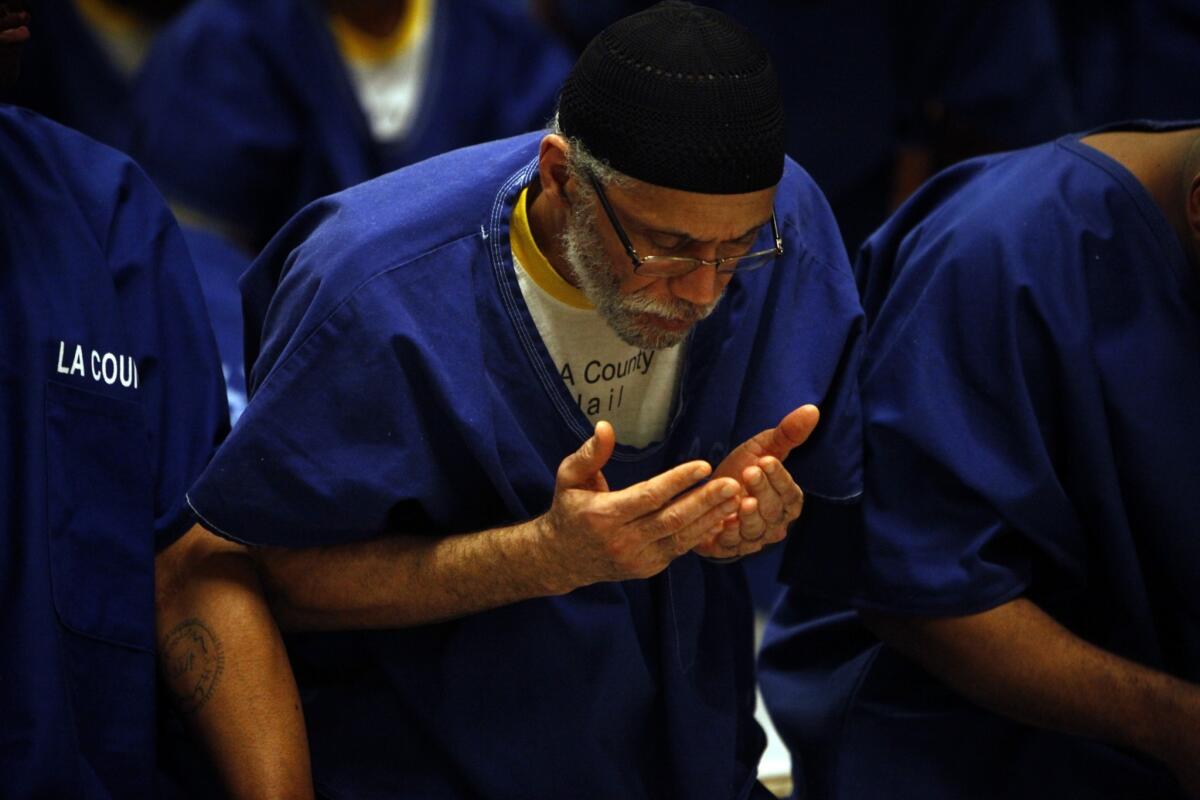

The inmate in blue jail-issue scrubs turned toward Mecca and sang the midday call to prayer heard at Muslim places of worship around Southern California on the last Friday of Ramadan.

About 80 other inmates, many wearing traditional caps called kufis with their jail uniforms, sat in the pews of a chapel in Men’s Central Jail during the service led by a volunteer imam.

Before sunrise, the inmates had consumed a breakfast of eggs, peanut butter and jelly, a banana and milk that conformed to Muslim dietary rules.

Now they were fasting until their evening meal, which they would eat together after sundown during a jailhouse version of iftar, the nightly Ramadan feast.

“It’s bringing me back to reality. I’m trying to stay on a straight path,” inmate Derek Cooper, 34, said of the month of fasting.

Since 2012, when the ACLU began complaining about the treatment of Muslim inmates in the Los Angeles County jails, the Sheriff’s Department appears to have made significant improvements.

Muslims in the county jails now receive halal meals. During Ramadan, a deputy at Men’s Central Jail works full-time with the Muslim inmates, ensuring they are fed the pre-dawn meal and that their other religious needs are met. Inmates no longer complain of verbal abuse from deputies denigrating the Muslim faith.

But until recently, Friday prayers continued to be a problem. While Jewish and Christian inmates congregated regularly in the jails, the Jumu’ah services took place only sporadically.

In April, the Sheriff’s Department issued a directive that Muslim inmates have a legal right to attend religious services. In the last few months, Men’s Central Jail has held a Jumu’ah every Friday, according to inmates, volunteer imams and jail officials.

Previously, there were only about 20 Friday prayers in two years, said Shakeel Syed, executive director of the Islamic Shura Council and a volunteer imam in the jails.

“We just want the same benefits they give to everyone else practicing their religion — Christians, Jews,” said Jerlone Barnes, 33, a Men’s Central Jail inmate.

Sgt. Juan Martinez, who runs the Religious and Volunteer Services unit, said the Friday services were limited because there were not enough volunteer imams to lead them. Recently, the rules changed, allowing an inmate to lead prayers under the supervision of a staff member or a volunteer chaplain from another faith.

“It’s an ongoing education,” Martinez said of working with inmates from different religions. “Once you keep doing it, it becomes normal.”

Next door at Twin Towers, which houses mentally ill inmates as well as some inmates who must be kept apart from others, security concerns prevent the 50 or so Muslims from meeting in a large group, Martinez said. Instead, volunteer imams counsel the inmates one on one.

Advocates for the Muslim inmates say the real test lies ahead, after Ramadan, which most concede has gone fairly smoothly this year.

“I’m really optimistic that this directive represents a serious commitment, a serious step,” said Jessica Price, an attorney with the ACLU of Southern California. “I hope that deputies will understand the religion better and the importance of respecting those requests.”

Complaints from incarcerated Muslims are common at jails and prisons around the country, said Hussam Ayloush, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations’ Greater Los Angeles office.

“What works against Muslim inmates is the politicized nature of how Islam is perceived in this country,” Ayloush said. “Even when it comes to the basic practice of bona fide religious beliefs, there’s always this angle of concern about how dangerous, how political, such a practice might be.”

In a statement, the Sheriff’s Department said it is committed to treating Muslims the same as those of other faiths.

“It is the Department’s hope that inmates will build a strong foundation based on positive values and beliefs through their religious faith that can lead to a new life path,” the statement said. “To that end, our goal is to ensure that inmates of all faiths can exercise their religious rights and that they are given the same opportunity to practice their faith.”

On Friday at Men’s Central Jail, Cooper and Barnes said they had each lost about 20 pounds during the Ramadan fast. Jail-approved prayer rugs are being distributed to inmates, but for now, both said they kneel on bedsheets to pray in their cells.

An inmate in light green scrubs and a black kufi took the pulpit, counseling his fellow Muslims to keep their faith when they leave the jail.

“You don’t want to be my age and still coming up these stoops,” he said. “Don’t be no Jumu’ah Muslim or no penitentiary Muslim.”

Inmate Malcolm Moore, 61, read a passage from the Koran about patience. In the end, he said, “You don’t need a prayer rug to pray.”

The volunteer imam, Adel Schumann, spoke about why Muslims fast during Ramadan.

“If you can control the core needs of your body … it’s easier to restrain yourself from committing sins,” he said.

Rising from their knees after the final prayer, the worshippers shook hands and hugged each other before heading back to their cells.

cindy.chang@latimes.com

Twitter: @cindychangLA

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.