Trailblazing

- Share via

Marcel Gillet sees the trail clearly in his mind: a smooth path about 5 feet wide with wildflowers popping from its perfectly angled side slope. Maybe there’s some sage growing there too. And maybe, just maybe, if his planning pays off, hikers will transcend their conversations, iPods or footfalls and feel like they’re gliding, even flying, down this stretch of the Backbone Trail.

But that’s more than a year away.

For now, Gillet gingerly slips heavy cotton green overalls over his uniform, stashes a pair of earplugs in a pocket, wriggles his fingers into thick leather gloves and sets out through snarly, dense brush, a dizzying maze of ceanothus in the western Santa Monica Mountains.

Gillet is a trail builder. A former construction worker, he started building access roads for the National Park Service 11 years ago and five years later, when the funding finally came through, he was tapped to blaze the missing links in the Backbone Trail.

Like a sculptor who sees life in blocks of marble, he sees a trail in the chaos of chaparral. Part artisan and part engineer, he can read the contours of a hillside, plot a path and bring it to life.

“People take trails for granted. They don’t think or know the painstaking work that went into it,” he says. “Building something like this feeds your soul.”

Suddenly the sound of a chain saw rips the air. Gillet wads his ear plugs in place and quickens the pace. Another push through the brush and five members of the trail crew materialize, bunched up single file, using tools they’ve lugged in on their backs to hack out an outline of the plotted route.

Wasps and snakes

The Backbone Trail is L.A.’s most prized outdoors possession. If ever a path captured the strange wonder of a wild course so close to urban clutter, this is it — a more-than-60-mile run winding along the spine of the Santa Monica Mountains between Will Rogers State Park in Pacific Palisades and Point Mugu State Park in Ventura County.Few trails in Southern California offer so much to see — from knobby volcanic ridges that seem imported from southern Utah to green-carpeted canyons that open up to small creeks where canyon sunflowers and ferns hide in the recesses. When the haze lifts from a 1,000-foot-high perch above the ocean, most of the Channel Islands appear in a single wide-angle view. And the oversized mansions, the satellite installations and Mulholland Highway? They just kind of come with the scenery.

Progress on the Backbone has inched along since construction started in 1986, moving only as quickly as land could be bought from private parties or cobbled together from existing state and county parks. When completed — one stretch is still being negotiated — the Backbone will be a genuine thru-trail — one that takes more than a day to complete — right here in our own backyard.

Gillet and his crew are working on a mere two-mile addition that won’t be finished until summer 2006. It will link a segment from Mulholland Highway, two miles northwest of Encinal Canyon Road, to a trail head at Yerba Buena Road. “It’s like driving the golden spike,” Gillet says.

Completing this section is a heady responsibility for Gillet. The 48-year-old with short wavy hair, a neat mustache and green eyes that match his Park Service uniform is responsible for maintaining and rehabilitating older, more poorly designed trails and dirt roads in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. This work burns up a lot of time and money, especially after a winter of battering rains.

Gillet’s crew is a disparate but congenial bunch. None of them look as if they could move mountains, but that’s exactly what they do, hauling the 70- to 80-pound loads required to keep a job that pays $14 to $15 an hour. They work nine-hour days facing dangers such as poison oak, Africanized bees and stinging wasps, and rattlesnakes — and that’s not counting mishaps such as being pushed down a hillside by a rock slide.

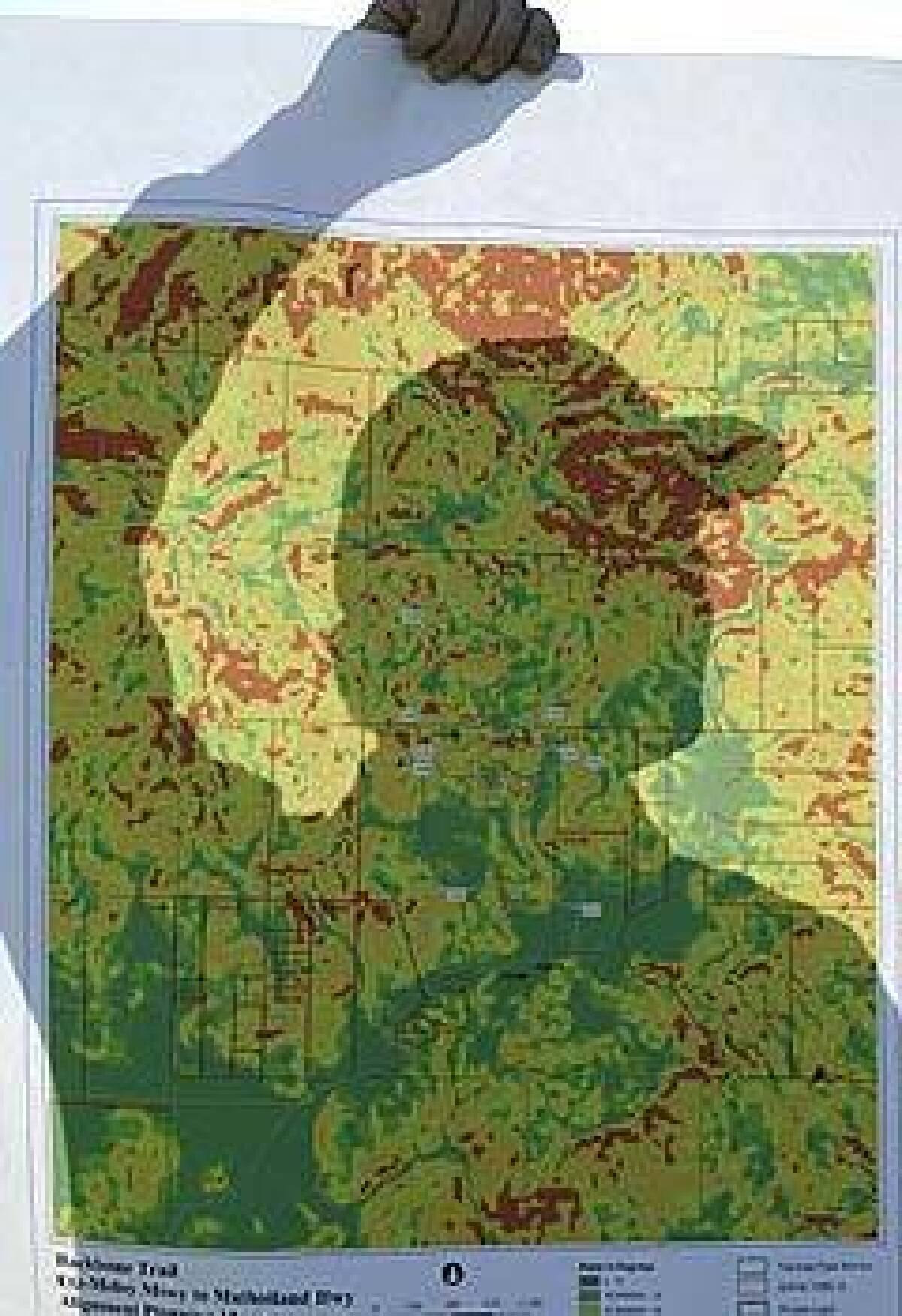

As they plod through the scratchy chaparral, the new route starts to take shape. They flag it by tying white ribbons to tree branches and planting blue flags in the ground. Transferring the purple squiggle of a trail from a topographic map onto a hillside has become second nature for them.

Every 100 feet, Larry Chirico cuts a slit in the brush with a chain saw. Nellie Navarrette and Mike Zenan grab freshly sliced, thorny branches and toss them off the trail. Darren Wright and Eric Ramos use a survey stick and a hand-held clinometer to measure and mark the grade with the blue flags. Wright frequently consults the map to make sure the route is on target. “Sometimes we can’t see five feet in front of our faces,” he says.

Despite the difficulty, they treasure the work. “It keeps me in shape, that’s my main reason for doing this, but I love being outdoors,” says Navarrette, 32, who’s back just seven months after having a baby. Navarrette’s parents never took her to these mountains when she was growing up in the San Fernando Valley, something she says won’t happen with her son.

The crew moves at a rate of 600 feet to 1,000 feet per day across the terrain, a painstakingly slow and exacting process comparable to making a light pencil mark that the clearing crew and mini-bulldozer will follow.

And no one — except for Chuck Hughes, a spotter who stands on a fire road above with binoculars to warn them about obstacles they can’t see, and Gillet — knows they exist. They are invisible now to the millions who will travel this future trail.

Few ever think about, let alone know the names of, the workers who make the purple line real.

Call in the dozer

Trail builders like Gillet will tell you that they aren’t just building a trail, they’re designing a future. Multiuse trails must have a 5-foot-wide trail bed and 8 to 10 feet of vertical clearance, standards adopted to accommodate hikers, cyclists, horses, people in all-terrain wheelchairs and babies in strollers.The goal is to create trails that will last a century, ones that keep erosion to a minimum and have the least impact on the environment. Good design, according to Gillet, costs $50,000 per mile.

But not all trail builders follow the same path.

At a recent workshop in Orange County, Kurt Loheit and state parks trail coordinator Frank Padilla Jr. are teaching park employees and volunteers the finer points of trail building. Loheit, a communications engineer with Boeing Co. in El Segundo, has 17 years’ experience and last year was inducted into the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame for his trail work.

As he zips through slides of rutted or caved-in trails, he lingers on one that shows a wooden trail sign where someone scrawled the word “hell” and an arrow pointing up the trail.

“What does this tell you?” he asks the class.

Silence. This is the difference between good and bad trail building.

Loheit is a champion of the old-fashioned methods and happiest when moving through brush with a Pulaski and a McLeod in his hands. With these tools, he works at a deliberate pace, preferring to interact with the environment on a more intimate level, one that values the work as much as the final result.

“As a species, we are hellbent on altering the environment, whether it’s [for] good or bad,” he says. “If we’re going to do [it], even down to the level of trails, you want to do that as best you can.”

Gillet, on the other hand, hasn’t the time to move so slowly. He says he can cut a trail three times faster with machinery and not burn out a crew. “You can’t push people like the slaves that built the pyramids,” he says.

If Loheit works with the equivalent of a fingernail file, Gillet prefers a Sweco, a mini-bulldozer for blazing paths.

After an archeologist and botanist have signed off on one of his routes, Gillet oversees what’s called “trail brushing,” a process in which all vegetation is removed as much as six feet on each side of the trail.

Then Gillet calls in the Sweco, which will cut the trail marked by the white ribbons and blue flags. The machine will return several times on this trail to shape side slopes, excavate drainage structures (at 75-foot intervals), then compact and drag. Add some hand-built drainage structures and signage, and the trail is ready to open.

Airborne

One late winter morning under hazy sun, Gillet walks a four-mile stretch of the Backbone off Yerba Buena Road that he designed. He’s traveled this route many times, and he still thrills to the sight of a crow riding the thermals below.Today he checks out a section that opened a year ago, a baby by trail standards. “I like walking on new trails,” he says, “especially after a first rain to see all of the water structures, see what’s functioning properly. Then I envision, ‘Wow, how great it’s going to be once it’s grown in.’ ”

He likes what he sees. So far only one culvert is packed with debris. Farther ahead, three boulders the size of wrecking balls have slid down the hillside and block the trail. But there are no ruts or washouts.

With the Backbone Trail virtually complete, Gillet’s job is pretty much over. He’ll be rebuilding or rerouting some of the older trails in the park, especially after this winter’s storms, but his dream now, he says, is to teach National Park Service workers the craft of trail building.

Talking as he walks, he suddenly slows his pace, as if channeling the trail, sailing over the undulating canyons. Below, four or five reddish boulders hide like a dragon in the brush.

And just as the ocean appears around a blind corner, you find yourself joining him, rushing ahead to see more, and you feel your feet lift from the ground, hovering over an expanse that draws you along an unstoppable course.

“Do you feel like you’re flying?” Gillet asks.

And you do.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.