Early intervention would keep more out of L.A. County Jail’s snake pit

- Share via

L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca has no medical background, but he is the de facto administrator of what he calls “the nation’s largest mental hospital.”

“This is the system,” he said, drawing a box on a piece of paper in his Monterey Park office last week.

Judges, prosecutors and law enforcement officials each have a role in deciding what to do with someone who has a mental illness and is accused of a crime, Baca said. But they decide each case in isolation, missing a broader concern — thousands of sick people get locked up, with no coherent plan for helping them get better.

“We put the criminal-justice priority ahead of the mental-health priority,” Baca said. “And those who are nonviolent, in my opinion, should be somewhere else” besides jail.

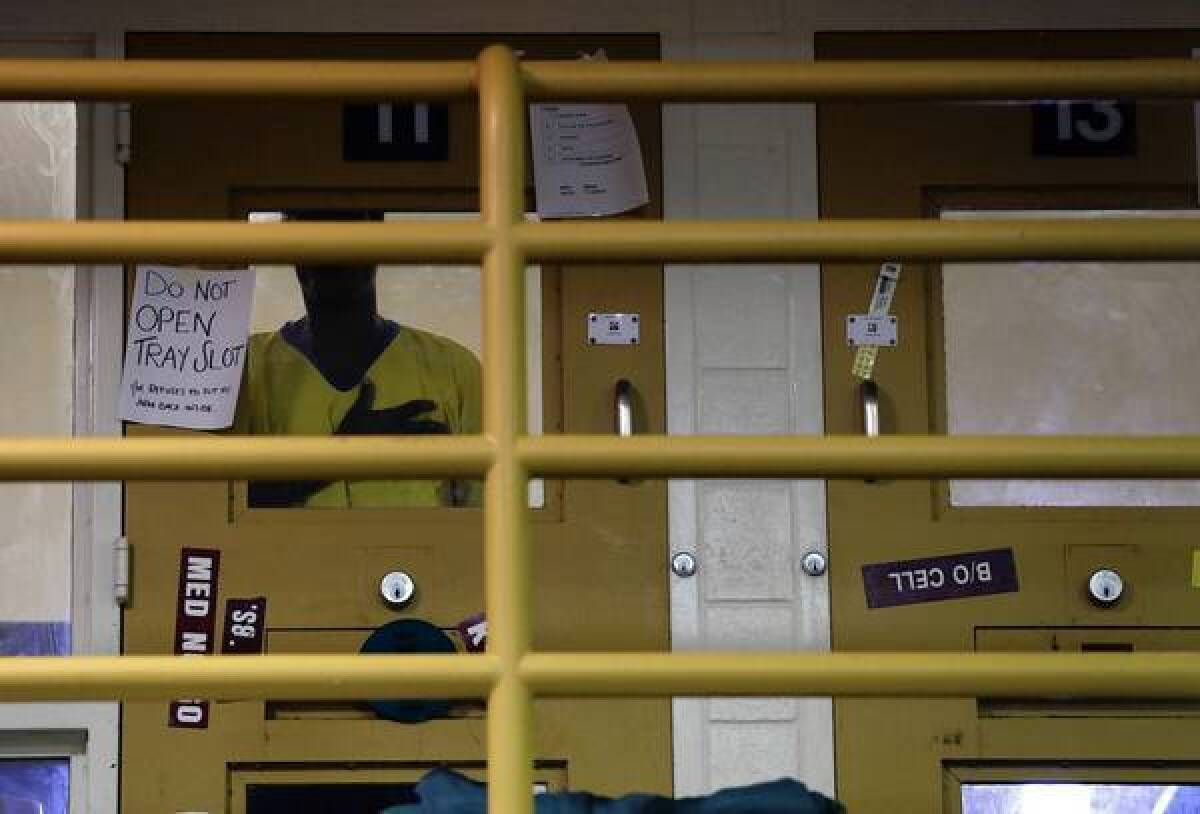

Four days before my visit to Baca, I spent several hours in the L.A. County Jail, where a staggering 3,200 people with mental illness were incarcerated. The images, described in my last column, were haunting.

One wing resembled an acute-care psychiatric hospital, with severely disturbed inmates in one-man pens. On another floor, cells were full, and a dozen or more inmates in each pod had to sleep in bunks stacked around a common dining area.

Most inmates have not yet been to trial and wouldn’t be in jail, Baca noted, if they had the means to make bail. They often go weeks between sessions with therapists, and when they’re released, most are back on their own, without supervised treatment. Recidivism, not surprisingly, is sky-high. One inmate told me he’d been through the revolving door 10 times; another 15.

The morning my column ran, I got a call from state Senate President Pro Tem Darrell Steinberg, who has done more to address the needs of California’s mentally ill than anyone in recent history. The two of us have connected on this subject since 2005, when I met and began writing about a homeless man named Nathaniel — a man I still count as both a close friend and a responsibility — who was diagnosed with schizophrenia 40 years ago while a Juilliard music student.

The good news, Steinberg said, is that “there are 27,000 Nathaniels that Proposition 63 has provided wraparound services to.” Steinberg is rightfully proud of the Mental Health Services Act he shepherded into being in 2004. Its programs have kept people out of jail and turned lives around. But we’re still chipping away at problems that date back to the 1960s, when California emptied mental hospitals, failed to build promised community treatment centers, and skid row populations exploded.

I often hear arguments for lowering the legal bar for involuntary commitment. For some people, who are sick and unable to care for themselves, I agree.

But such commitments wouldn’t be necessary if we had adequate intervention and more courts with authority to send people to treatment rather than to jail. Housing someone with needed services costs about a third of what it costs to incarcerate.

Steinberg reminded me that he fought for and got $200 million in additional funding for mental health services in the current state budget, which will add, among other things, 2,000 crisis-stabilization beds.

“I associate that with 2,000 lives saved,” said Steinberg, who believes we have a moral duty to those afflicted with mental illness through no fault of their own, including thousands of veterans.

Last Tuesday, dozens of speakers urged the L.A. County Board of Supervisors to invest in keeping people out of jail rather than consider building a new one for roughly $1.5 billion.

“This is not an either/or proposition. We need both,” Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas later told me, citing several mental health programs the county is investing in. But Ridley-Thomas added that some inmates “cannot function well in an outpatient setting,” and the county owes them jail facilities that aren’t “dilapidated … cesspools.”

Getting back to Baca, I’ve been hard on him over the alleged abuse of inmates by deputies and other examples of mismanagement. On the subject of mental illness, though, he’s long been one of the more progressive voices in law enforcement.

When I asked why, he showed me a photo of his late uncle William, who was developmentally disabled. Baca said that through his own childhood, he shared a room with his uncle. Later, as a young deputy, he was on duty one day when he heard a radio call about the involuntary commitment of a man in the midst of an apparent psychotic episode. The man turned out to be Baca’s cousin, who died shortly thereafter in the hospital at the age of 42.

That explains Baca’s sensitivity to the issue. But has the sheriff done enough beyond telling us he runs a mental hospital?

“No. I haven’t done enough,” he said, adding that he needs to step it up.

He recommended intervention at the point of arrest, with low-level offenders taken to an evaluation center and assigned to treatment rather than incarceration. For those who have to be locked up, he added, there needs to be better linkage, upon their release, to long-term supportive programs that could aid in their recovery, so they’re not arrested again, and again, and dumped into the nation’s largest mental hospital.

“We’re in the 21st century,” Baca said. “We shouldn’t be using 18th century solutions for this problem.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.