Massive earthquakes cracked the very foundations of the tiny but tough town of Trona

- Share via

Reporting from Trona, Calif. — Under the shade of a salt cedar tree, next to a shipping container and near a sign that said “Prayer Changes Things,” the Byrds of Trona had camped out overnight and planned to for the foreseeable future.

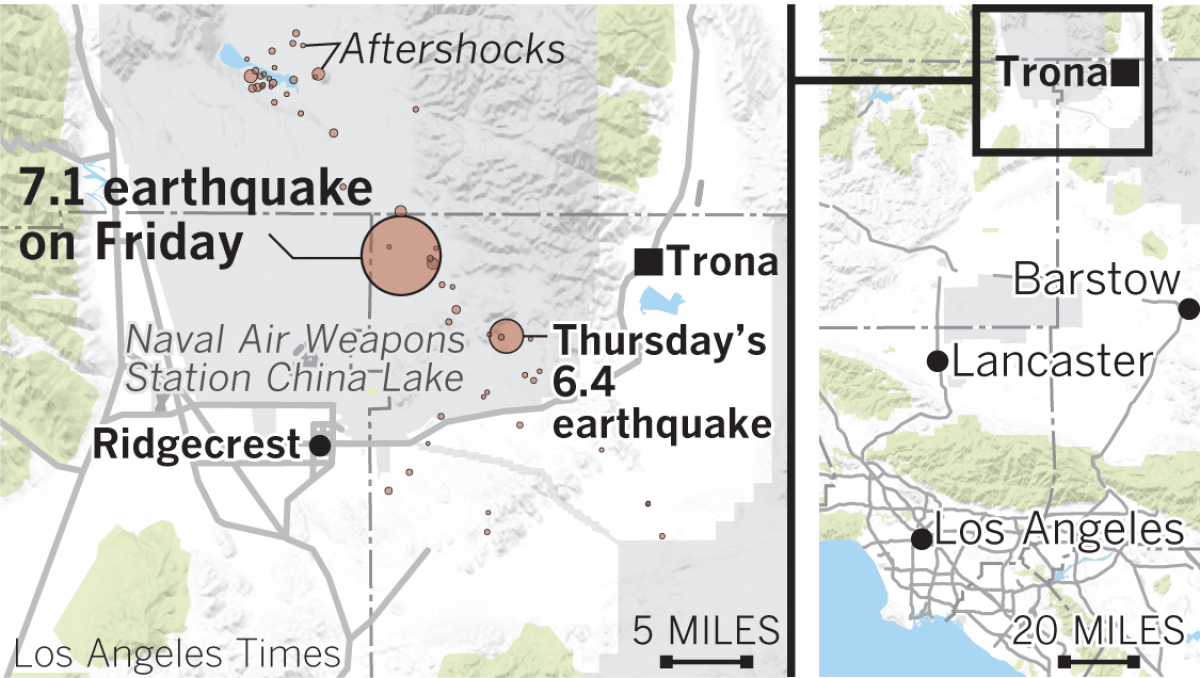

A sleeping bag was laid out on the patchy grass. Bags of chips and candies surrounded a basket of green apples and fruit on a picnic table. The Byrds — mother Kay; father Fred; sisters Karen and Cynthia Thompson; and the latter’s daughter, Brooke — were trying to re-create a household after two major earthquakes. A magnitude 6.4 foreshock on Thursday, then a magnitude 7.1 rumbler the following evening had wrecked their town of 2,000 and left them scared.

They refused to return to their home of 21 years.

“The first one was devastating,” said Karen, as her niece played with Littlest Pet Shop dolls on a sleeping bag. “The second one was terrifying. And they say a bigger one might come. They were right about the second one, so why risk it?”

Across Trona, an unincorporated community on the edge of Death Valley long mythologized in California for its desolate location and tough character (the high school football team is one of the few, possibly the only, in the United States to play on an all-dirt field), residents are still cleaning up after the quakes.

And though it’s hard enough to live here even in the best of conditions, many Tronans say they now face a reckoning about their future.

The twin temblors cracked the very foundations of the town. A chimney stack at the Searles Valley Minerals plant, long Trona’s economic lifeblood, partially toppled. Graves caved in at the cemetery. The sign at the only park crumbled. At Esparza Family Restaurant, where locals gather at 5:30 in the morning every day, a massive fracture blights its outside mural.

Water is inaccessible. Electricity is spotty. Dozens of homes have broken walls, split driveways or interiors that look like one of the hard winds that regularly sweep through town blew right through them. As of Sunday afternoon, cars still needed escorts in and out of Trona on Highway 178 from Ridgecrest, about a half-hour drive away, because of a phalanx of construction crews placing new asphalt.

Even the sulfur stench that usually pervades the air in Trona is more noticeable by its absence. The Searles Valley Minerals plant is shut down.

“If they don’t get up the mine,” Kay said, “the town is finished.”

A struggling town

Trona sits at the edge of a dry lake from which various companies have extracted minerals such as borax and soda ash for over a century, and its neighborhoods are roughly planned around four plants, all connected by long, winding Trona Road.

In the 1950s, it had the makings of any respectable town: bowling alleys, a Fox movie theater, a hospital, a large pool. At its height, it had 6,000 people.

But Trona’s fortunes soured as the Navy expanded its China Lake station and nearby Ridgecrest grew. Mining jobs became scarcer; many residents grumble that the current plant owners, Nirma Ltd., are based in India and don’t care about their well-being like previous bosses did.

Earthquake batters Trona: Rockslides cut off town; water is scarce »

The population has declined dramatically, along with the aesthetics; abandoned homes litter the already parched landscape. On the way into town, someone spray-painted a sign advertising a San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department substation with the face of a pig.

“The town is not too good right now,” said 80-year-old Gail Austin, who has lived in Trona nearly his entire life and retired in 2000 as a Searles Valley Minerals plant manager.

“There is a bit of a drug class,” admitted Larry Cox, pastor at First Baptist Church of Searles Valley, which had to cancel its 65th anniversary celebration after the roof of its fellowship hall caved in.

“It’s gone from being a great town where we had everything to one where we only have ourselves,” said Ralph “Zeb” Haleman, who was eight stories up at the main minerals plant when the second quake hit.

People had tried to rally community spirit in recent years. The nonprofit Trona Care has bought abandoned houses to tear them down. There were plans for a new park, redeveloped apartments. A Family Dollar opened in 2015.

It hasn’t been open since Thursday.

In front of Trona High School, where residents lined up to get cases of water, oatmeal cookies and vegan Chinese food brought by good Samaritans from Perris, Ricardo Romo tended to his four pit bulls. They were in a cage in the back of his truck. He was on his way to Joshua Tree, accompanied by his dad and other family members.

“My house is wrecked,” he said. “And I don’t know if we’re going to have a job on Monday.”

When the quake hit these Trona families, ‘everything came tumbling down’ »

“If there’s another big one, Trona will be gone,” said 76-year-old RoseAnn Austin, who has lived here since 1963. Her main house didn’t see much damage. But a property across the street saw its front fence completely ruined; cinder blocks were spilled across the sidewalk and covered a large pile of wood that the Austins had left for chipmunks to live in.

“Our chipmunks don’t know what to do,” Austin said. “They don’t know where to go. I hope they have enough food stored away.”

Community spirit

Other residents have buckled down.

Tommy Channell, originally from Victorville, has lived in Trona only since October but said he quickly found a community groove he had never previously experienced. After the second quake, he immediately got a crescent wrench and went around his neighborhood volunteering to shut off gas lines.

“I’m 40, but this is the first time I’ve found a real home,” he said. “It looks ugly from the outside, but inside, it’s a lot of love.”

First Baptist Church served as a water station and had the men of its congregation go from home to home to check in on “widows and shut-ins,” Cox said. St. Madeleine Sophie Barat Catholic Church, usually open only twice a month, planned to hear confessions.

Full coverage: 2nd major quake in two days hits Southern California »

At the Christian Fellowship of Trona, where the power was out, about 12 congregants stood in the sanctuary room to gather information they’d pass along to others around town. Tips came fast: The Red Cross was going to have a bigger presence from now on after a miscommunication the day before. Beware of price gouging in town. People from around the world want to donate money, so who can help set up a GoFundMe page?

Julia Doss, who runs a Trona Neighborhood Watch Facebook page, did most of the talking. She said that 40 sack lunches someone had donated were “grabbed in no time,” and that what the town needed most besides water and ice were diapers, wipes and gallon-sized Ziploc bags.

Doss, who works at Searles Valley Minerals, noted that there were a lot of newcomers in town. “As a community, we’ve gotten used to keeping to our friends,” she said. “Now is a time to learn who [strangers] all are.”

Those present nodded. They were enthusiastic but tired. Seven aftershocks with magnitudes of at least 3.0 had already struck Trona on Sunday morning.

“Try to get a little bit of rest,” Doss said with a smile, “between the shivers and shakes.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.