Mothers’ 26-year quest for justice takes them to state Supreme Court

- Share via

It has been 26 years since the two mothers last saw their young sons, boyhood friends who hopped on their bikes one Saturday afternoon to enjoy burgers and candy and never came home.

But on Wednesday, Milena (Sellers) Phillips and Maria Keever sat in the chambers of the California Supreme Court in San Francisco listening to a lawyer argue why the sexual predator who murdered their children should have his death penalty sentence overturned.

“As long as we’re alive, anything that has to do with our children, we’re going to be there,” Phillips said.

Ever since Charlie Keever, 13, and Jonathan Sellers, 9, were abducted, raped, tortured and killed by the banks of the Otay River in 1993, Phillips and Keever have been searching for justice and some semblance of peace.

“Just about every night I cry and talk to Charlie. Every night,” said Keever, 72. “It’s like a tape recording in my head. From the minute it happened, it just goes on and on. I don’t know how I’m not crazy.”

When she talks to her son at night, Keever asks Charlie for help. “And then I thank God for what I’ve got. I’ve got a roof over my head and food. And I think Charlie is with me. I feel him. I know he is with me.”

Keever said a few years ago a man came to laminate a floor in her house, the same house where she raised her son in the South Bay neighborhood of San Diego.

“He didn’t know the story. He told me he had seen a little boy running in the kitchen. I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Yeah, I didn’t think you had any kids.’ And then I told him the story. His hair on his arms was standing up. He was so shook up. Isn’t that weird? I knew Charlie was in the house.”

For eight years, the crime that detectives testified was the worst they had ever worked went unsolved. Then advances in DNA testing locked on a suspect, Scott Erskine, who was already serving a 70-year sentence for the brutal rape of a woman that took place later in 1993.

From 2002 until 2004, the mothers attended numerous hearings in San Diego Superior Court as the death penalty case against Erskine progressed. He was found guilty and, after two penalty phase trials, sentenced to die. He has been on death row at San Quentin ever since.

Last week, the first of what promises to be many more automatic appeals of the sentence was heard by the state Supreme Court justices.

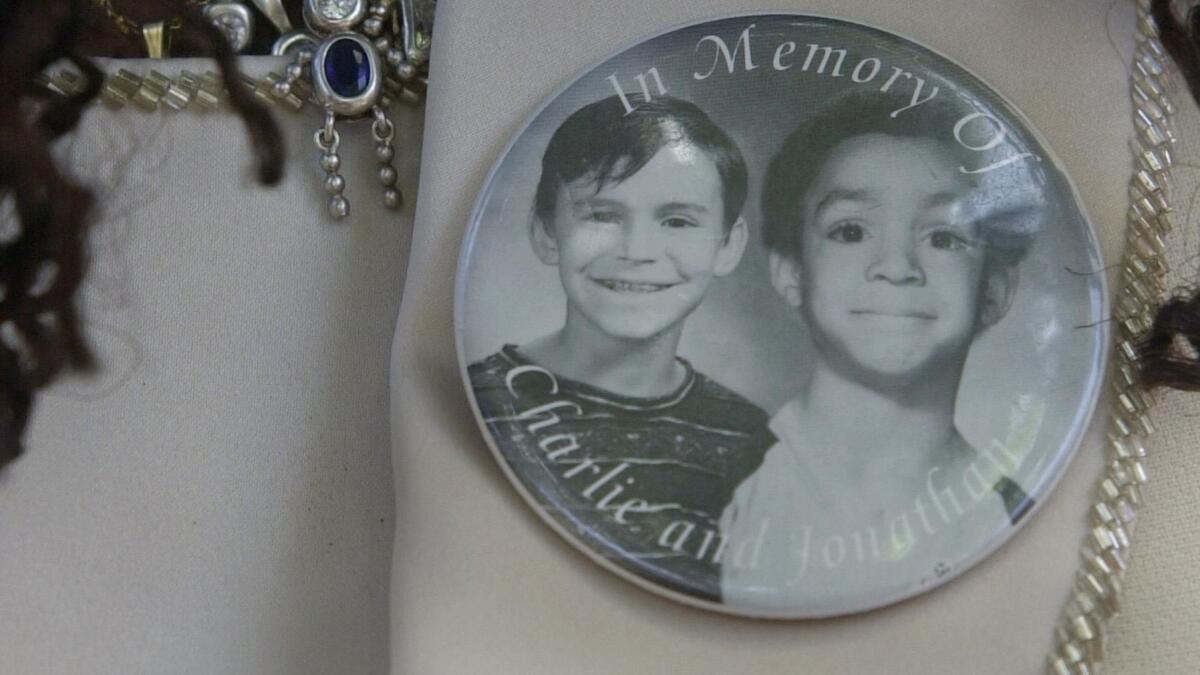

Phillips and Keever were in the gallery. Draped around their necks, as always, were necklaces with photos of their boys.

It will be 90 days before the justices rule on the appeal, but lawyers with the Attorney General’s office told the mothers after the 20-minute hearing that they were confident it would be rejected.

But they warned this was just the beginning, with many more appeals to come.

The mothers know Erskine will almost certainly never be put to death. California hasn’t executed anyone since 2006. And the list of death row inmates hovers around 750, with Erskine far back in the pack.

“I’m realistic,” Phillips said. “They told me it’s not going to happen. I only want him on death row because he doesn’t want to be there. The punishment on death row is different than the punishment they give for life in prison. I want him on death row, by himself, period. End of discussion. He will not make new friends. He will not be watching movies with other inmates. No. He doesn’t deserve it.”

Both said Erskine’s freedom should be limited to his small death row cell.

“Look how much space my son and Charlie have,” Phillips said. “They’re in coffins, forever. Look at their space.”

On the flight to the Bay Area on Tuesday, Keever said she wished the trip was to view Erskine’s execution. Both women would like to witness that.

“I don’t feel like it’s revenge; it’s just justice,” Phillips said. “You don’t kill kids. You don’t kill people. We’re talking innocent kids doing nothing. He purposely murdered them for his own sexual pleasures. He needs to be punished. That’s not revenge. I don’t believe in revenge. I do believe in justice.”

They were comforted by Deputy Atty. Gen. Robin Urbanski, who argued the state’s case and later told the women she will follow the case for as long as it takes.

She said there are plenty of cases she would gladly pass on to another attorney, “but not this one. I have only a handful I can say that about.”

“Thank you,” Phillips said.

Keever also came out of the hearing with a ray of hope.

Erskine’s attorney, Kimberly Grove, said her client, now 56 years old, is ill and recently was hospitalized for heart and lung problems. Grove said she would encourage Erskine to speak with Keever, something Keever has been trying to do all this time.

Twice in the early years of his death row incarceration, Keever went to the prison to speak with Erskine, but he declined.

Keever wants to know every detail of what happened to the boys. Many specifics were covered in gruesome detail during the trials. What nobody knows is how Erskine lured the boys into a man-made brush enclosure by the river, where they were found two days later.

Keever hopes Erskine will tell her, especially now if his health is poor and he realizes his time is short-lived.

“I think if he would talk to me, it would give me more peace,” Keever said. “If I knew what happened, how he took them. Milena doesn’t want to know, but I want to know. I think it would make me feel better. Because right now, all I know is what I imagine. Maybe I’m imagining worse things than what really happened. I want to know how he got them. That’s what bothers me, not knowing.”

All death penalty sentences are automatically appealed directly to the Supreme Court. The brief prepared by Erskine’s lawyer numbered hundreds of pages, but Grove chose just one issue to focus on during the hearing. It had to do with the dismissal of one juror by the court during the second penalty phase trial (the first ended with the jury hung 11-1 for death). The argument was that the juror had said she was opposed morally to the death penalty, but could set her beliefs aside and follow the instruction of the court.

It’s an argument that has been made often in other cases without success, attorneys said.

The justices asked only a couple of brief questions.

During a Lyft ride back to a motel after the hearing, the driver, listening to snippets of the conversation the women were having in the back, asked why they were in town.

He was shocked when he heard the reason, a look of admiration mixed with pity in his face.

There is a park at the south end of San Diego Bay that was dedicated in 2012 to the boys’ memory. The Sellers-Keever Park is along the Bayshore Bikeway at the end of 13th Street .

There is the Jonathan Sellers and Charlie Keever Foundation, run by the moms. Its mission is to promote the safety and well-being of children through education to prevent child abduction and exploitation, and provide support to families who’ve lost a loved one to violence.

Phillips is a nurse at a Fallbrook elementary school, one of several jobs she has, many of which have to do with Jonathan’s murder. She lectures police on how to deal with parents of abducted kids and has written a children’s book aimed at keeping children safe. She is also an actress, having performed in many local theatrical productions. Right now on television, a Mor Furniture ad begins with a shot of her happily jumping onto a couch with a little girl in her arms.

She and Jonathan’s father divorced the same year their son was killed. She remarried in 2008 and moved to Fallbrook with her husband, Clyde Phillips, where they are now legal guardians to a 9-year-old boy.

Jonathan was 9 when he was killed on March 27, 1993.

Just before Jonathan and Charlie took off on their bicycles that day, Jonathan reminded her he was going to be turning 10 in less than three weeks.

“The scene that keeps playing over and over in my head is Jonathan coming into the house,” Phillips said. “He asked for his bike lock, reminded me he was going to be ‘the big 1-0’ soon, and gave me a big wet kiss.”

She said she plans on making sure the boy she is raising now has a very special 10th birthday.

J. Harry Jones writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

Jones writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

jharry.jones@sduniontribune.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Vista, California-Apri 2, 2025-Hours after undergoing dental surgery a 9-year-old girl was found unresponsive in her home, officials are investigating what caused her death. On March 18, Silvanna Moreno was placed under anesthesia for a dental surgery at Dreamtime Dentistry, a dental facility that "strive[s] to be the premier office for sedation dentistry in Vitsa, CA. (Google Maps)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/07a58b2/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2016x1344+29+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F78%2Ffd%2F9bbf9b62489fa209f9c67df2e472%2Fla-me-dreamtime-dentist-01.jpg)