Seismic safety wins a round in Trump budget battle

- Share via

First, a congressional panel voted last week to keep funding a West Coast earthquake early warning system that could have been shut down under the proposed budget.

Then, a different subcommittee voted to continue funding a global tsunami detection system that gives U.S. officials an accurate forecast of when and how big floodwaters will arrive from a distant earthquake.

The House of Representatives’ appropriations subcommittee overseeing the Department of Commerce voted Thursday to reject a provision in Trump’s proposed budget that would have ended funding of the U.S. deep-ocean tsunami sensor network.

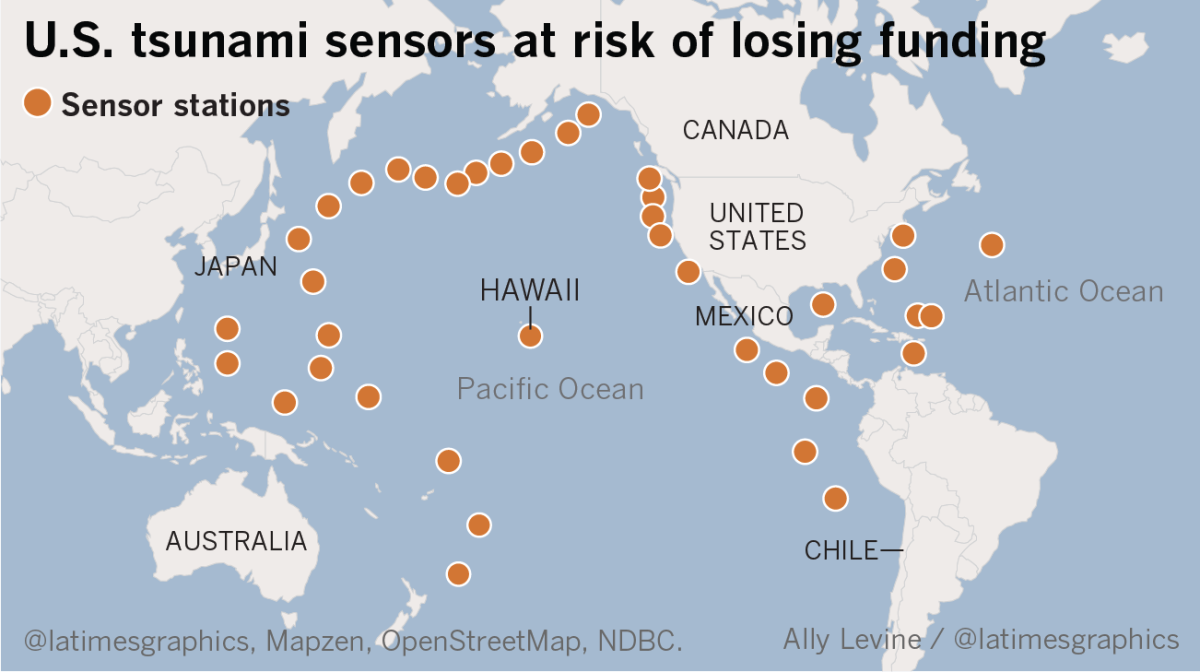

Ending funding for the $12-million network would have eventually shut it down, as batteries for the system’s 39 stations, located on sea floors around the world, would run out of power in about two years.

The deep-ocean tsunami sensing system was built after a false tsunami alert in 1986 caused a costly, unneeded evacuation of Honolulu’s famed tourist district, Waikiki, trapping cars in the evacuation zone and costing the state tens of millions of dollars.

The system was modernized and expanded to its latest incarnation after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which killed more than 235,000 people and underscored the dangers of an inadequate tsunami warning system.

No deep-ocean sensors existed in the Indian Ocean when that tsunami struck, and the disaster led then-President George W. Bush and Congress to back the creation of a U.S.-led global tsunami sensing system, which increased the number of deep-ocean sensors operated by the U.S.

The panel also rejected a proposed reduction in funding for the U.S. tsunami warning centers. The Trump administration suggested cutting the number of tsunami warning centers from two to one and slash staffing from 40 full-time employees to 15 — saving $11 million.

“The committee does not adopt the proposed reduction for the Tsunami Warning Centers ... or the Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART) buoys,” a subcommittee report said.

Congressional aides said the subcommittee also rejected a proposal to end $6 million in grants given to states to reduce tsunami hazards, which fund emergency drills and the drawing of flood maps and evacuation plans.

A document explaining the Trump administration’s plan acknowledged that “tough choices” were made to reduce funding, but “is necessary as we move toward a more efficient government that re-focuses on national security and core government functions.”

The sensing system operates on a simple premise: recording the tsunami as it races through the deep ocean, before it strikes the shore.

Officials long ago realized that simply relying on how big an earthquake is in the ocean cannot accurately predict a tsunami. Sometimes, big earthquakes produce no tsunami, and at other times a moderate temblor might conjure up a tsunami surprise.

The solution developed by NOAA scientists was to send ships into the deep ocean and drop sensors that would sink to the sea floor, according to Eddie Bernard, a former director of the U.S. Pacific Tsunami Warning Center and a key architect of the system. The sensors would detect the tsunami as it rushed through and then send signals to a connected floating buoy that would send data to the warning centers by satellite.

The panel also rejected a proposed $11-million cut for the National Mesonet Program, a network of automated weather stations that can indicate rapidly deteriorating weather conditions. If the cut had gone through, NOAA would not have been able to monitor these conditions in all 50 states, and would have had to “prioritize states most susceptible to tornadoes and severe weather.”

Also reversed was the proposed termination in an investment to extend operational weather outlooks from 16 days to 30 days, saving $5 million, and a suggested halt to a project that would improve tornado forecasts in the southeastern United States, which would have also saved $5 million.

The budget proposal will next be considered by the full House Appropriations Committee, and eventually the full House of Representatives and the Senate will weigh in before a budget is sent to Trump. The next budget year begins Oct. 1.

The president’s budget proposals can be changed significantly by Congress, which takes over the process once the administration submits its recommendations.

A separate congressional subcommittee, which oversees the Department of the Interior, said last week that the U.S. Geological Survey should be allowed to continue receiving the same $10.2 million the earthquake early warning system received in the last budget. The system is expected to begin limited public operation by next year if the network continues to receive stable funding.

Rep. Ken Calvert (R-Corona), chairman of the subcommittee, said last week he has been a big supporter of the earthquake early warning system and was the architect behind the decision to allocate $10.2 million to the system in the last budget year.

Calvert said the funding has backing from both parties.

ALSO

Earthquake denial gets a lot harder when you stand on top of the San Andreas fault

Threatened by Trump's budget, tsunami warning system gets backing from congressional panel

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.