San Bernardino County’s smallest city faces big financial woes

- Share via

Reporting from ADELANTO, Calif. — For four decades, the smallest city in San Bernardino County fought them. But the financial burdens that have troubled this city since its incorporation 44 years ago have finally caught up to it.

Back in 1970, San Bernardino County staffers recommended against allowing this lightly populated swath of high desert to incorporate, arguing that it was “hard to see how a city of this size could rank with other cities of California.”

Despite the warning, the residents pushed ahead, believing retail would come in and boost city revenues, allowing it to grow and flourish.

Since then, the hoped-for arrival of major retailers has not materialized, and the city has barely scraped by, often balancing its budget by relying on grant funds, investment income or other one-time revenue sources.

Last year, Adelanto’s luck ran out.

The 56-square-mile city of 32,000 declared a fiscal emergency in June 2013 to remain solvent through 2014. As part of an effort to cut its $5.5-million deficit, the city laid off 19 employees (23% of its workforce), closed one of the town’s two fire stations and cut the sheriff’s department’s administrative staff.

Adelanto is still $2.6 million in the hole.

“You could lay every employee in the city off and you’d still have a $100,000 deficit,” said City Manager James Hart. “Cutting employees or their salaries isn’t going to get you where you need to be. There needs to be additional revenue.”

Now officials are asking voters to pass a 7.95% utility users tax in November to keep the city afloat. If approved, the tax would be in place for seven years with the option to lower the rate if finances stabilize. Low-income seniors would pay a discounted rate of 5.95%.

“It isn’t a matter of need or want,” Mayor Cari Thomas said at a recent City Council meeting. “We need this.”

If voters do not approve the utility users tax, Thomas says the city will file for bankruptcy.

The crisis has been brewing for years.

When the housing market crashed in 2008, building in the city stopped and the development fees paid to the city dried up. While Adelanto’s tax revenue remained stagnant, costs for the San Bernardino County sheriff’s and fire departments went up. This year, the cost of those agencies is $7.4 million, a $390,000 increase over 2013. The city’s estimated tax revenue for 2014 is $4.6 million.

In 2010 the city sold the Adelanto Correctional Facility to the GEO Group for $28 million and, anticipating the dire financial situation, allocated that money to cover the budget deficit over the next five years.

All they had to do, officials thought, was get one anchor store to boost sales tax revenue and others would follow.

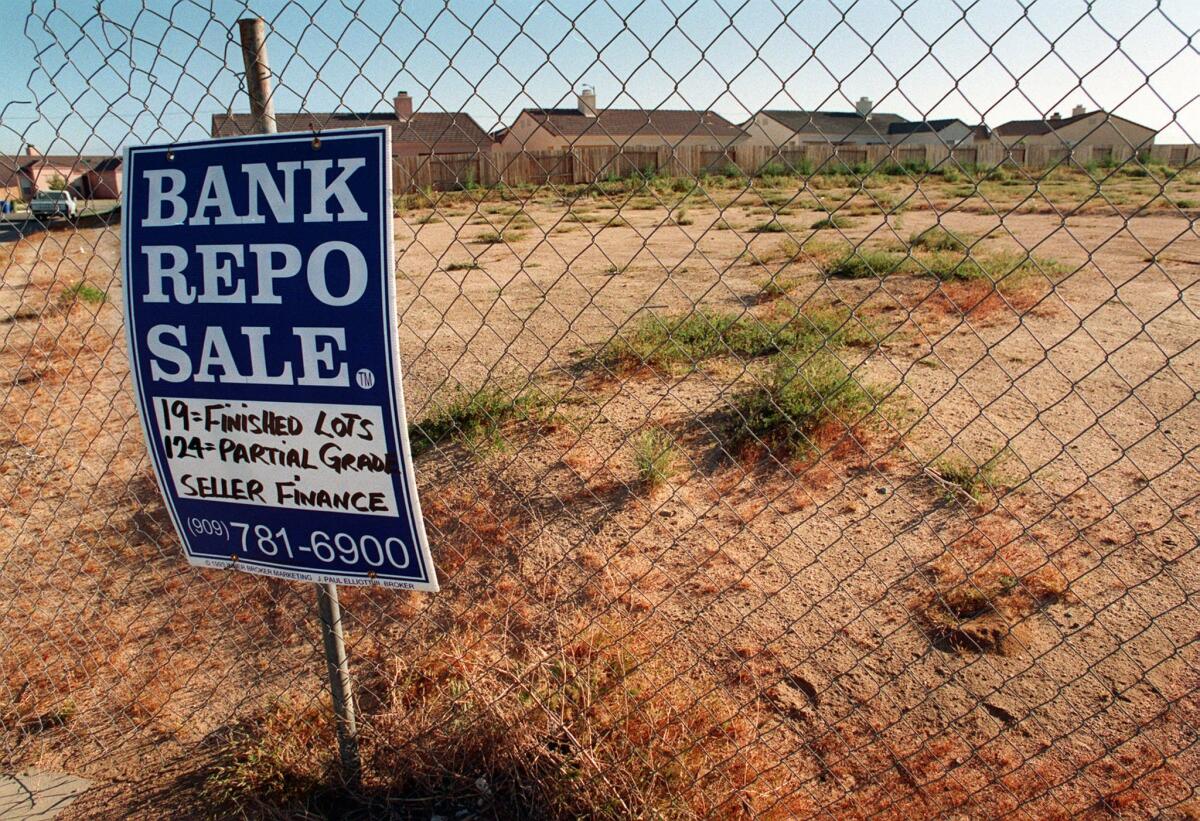

During a housing boom in the mid-2000s, Target bought land for a store in Adelanto. But after the housing crash, the land sat empty year after year.

“We really in our heart of hearts thought Target [was] going to start building,” said Thomas, who was elected to the City Council in 2008. “We thought once it was successful someone else would come.”

Target pulled out completely earlier this year, leaving Adelanto with few options for additional revenue.

The city hopes to get it from the proposed utility users tax. But Adelanto’s residents have weathered a 120% increase in water and sewer service fees in recent years, which makes some of them hesitant to add to their tax burden.

“My frustration is I’ve seen how you handle money and just because I give you more money doesn’t mean you’ll do better,” said resident Kim Smith, who is opposed to the utility users tax.

The city’s history of mismanagement and corruption also makes the pitch for a tax an uphill battle.

Former Mayor James Nehmens and his wife were sentenced to six months in jail in 2008 after pleading guilty to charges of embezzling thousands of dollars from the city’s Little League.

In 1997, Philip Genaway, former chief of the now disbanded Adelanto Police Department, was sentenced to four years in prison for embezzling nearly $10,000 from the canine unit. Two of his officers went to prison the same year for beating two handcuffed suspects and forcing one to lick his blood off the police station floor.

But Teri Ortega, a resident of Adelanto since 2004 and president of the Adelanto Chamber of Commerce, said those cases are part of the past. She said she favors the tax because the alternatives — bankruptcy and disincorporation — would leave her paying more for fewer services.

Disincorporation has not happened in California since the 1970s. At this point, it is unclear what services and at what cost the county could provide in either case.

Adelanto officials insist they have done everything they can to stave off the looming threat of bankruptcy, including trying to sell the city-owned minor league baseball stadium, which has lost $2.5 million since it opened in 1991 in an attempt to bring more traffic and development.

“I’m not guaranteeing anybody anything,” said Charley Glasper, a former Adelanto mayor who sits on the citizens’ advisory committee that proposed the tax. “But I’m in favor of doing something besides sitting there and doing nothing. I’m not going to give up on my city. I love this place.”

james.barragan@latimes.com

Twitter: @james_barragan

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.