A wary hold on 9/11 trials

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The Defense Department had an eye on history Monday when it announced capital murder and war crimes charges against six detainees at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, saying the alleged Sept. 11 plotters would be given an “extraordinary set of rights” when they go on trial.

They will receive more rights than the top Nazis tried at Nuremberg, military officials pointed out, and far more than the plotters in the assassination of President Lincoln, who were hanged within three months.

Still, the tribunal will be run by the U.S. military, with military lawyers and military judges. Even Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates has said that trials at the island prison would carry “a taint.”

Those proceedings could begin as early as summer, following the decision by military prosecutors to charge the suspects -- including self-proclaimed Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed. Prosecutors have recommended that all six be put to death if found guilty.

Each of the men was charged with conspiracy, murder and other offenses. Four were accused specifically of hijacking the airliners that hit the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, as well as the one that crashed into a Pennsylvania field.

When military tribunals were first convened at Guantanamo nearly four years ago, the rules allowed prosecutors to use secret evidence and to consider information gathered through torture. The Supreme Court in 2006 struck down those commissions because they violated the Geneva Convention.

Under a law since passed by Congress, the Pentagon has gone a long way to change the rules governing terrorism trials. Even critics acknowledge that they now more closely mirror civilian trials or military courts-martial.

Gone, for instance, are provisions allowing secret evidence. All evidence, even that considered classified by the government, must be shown to the accused.

Gone too is the allowance for evidence gathered under torture. However, the question of whether prosecutors may use information obtained through controversial forms of coercion -- particularly the simulated drowning practice called waterboarding, which critics consider to be torture -- will be left up to individual trial judges.

Perhaps most important, defendants can appeal convictions to U.S. civilian courts, including the Supreme Court.

Despite the tightened rules, the court of public opinion may never be convinced that the trials of some of the world’s most notorious suspects will be fair and credible.

“It will never be judged to be legitimate, not by those who despise us . . . [and] not by our staunchest allies,” said Jack Cloonan, a former FBI agent assigned to the Osama bin Laden squad in the New York field office. “A military judge, a military prosecutor and defense team and essentially a military jury -- even our staunchest allies can’t look at this with any sense of justice.”

Officials involved in drafting the new rules under the Military Commissions Act of 2006 said lawmakers took as their guide the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the well-regarded system for courts-martial. Some human-rights advocates have been urging the use of the military justice system for the Guantanamo prosecutions.

Charles D. “Cully” Stimson, who oversaw detainee affairs at the Pentagon until resigning last year, said courts-martial and the military commissions were “virtually identical in 98% of the rules.”

Still, advocates of the military commissions acknowledge that the new procedures fall short of all protections provided in civilian courts and under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

The Guantanamo commission rules allow for more liberal use of hearsay evidence -- information gathered second- or third-hand. And in other U.S. courts, almost all testimony gathered under extreme duress would be ruled out automatically, not left up to the discretion of the trial judge, as military commission regulations permit.

Questions concerning information-gathering techniques could become particularly contentious, given the recent CIA admission that three detainees -- including Mohammed -- were subjected to waterboarding, a practice that administration officials say has led to a trove of intelligence.

“The rules are so loose that, you know how they say a grand jury can indict a ham sandwich? A military commission can convict that sandwich through torture and hearsay,” said Jumana Musa, who has tracked the Guantanamo trials for Amnesty International.

Charging documents released Monday by the military give no indication whether prosecutors intend to use evidence gathered under coercive questioning in the trials of the six alleged plotters.

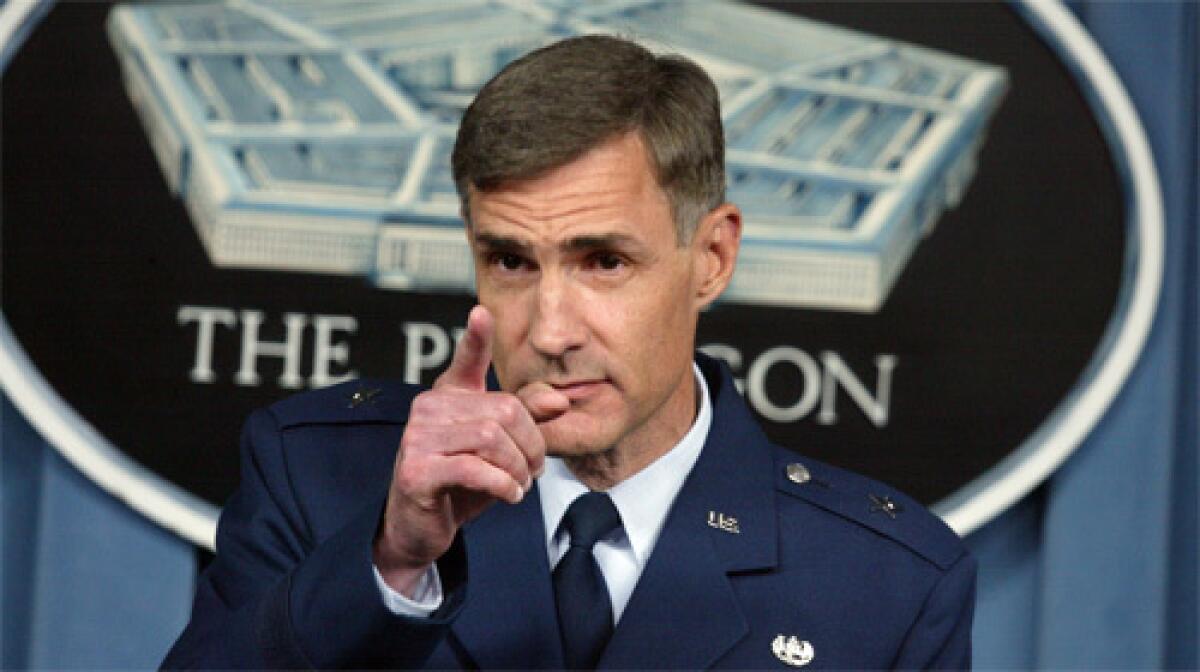

Air Force Brig. Gen. Thomas Hartmann, one of the military lawyers who will decide whether the cases can proceed to trial, told reporters at the Pentagon that he did not know yet whether such evidence would be used.

But he defended the practice, noting Congress explicitly allowed for a trial judge to decide whether information gleaned through questionable interrogation tactics should be allowed.

“The question of what evidence will be admitted, whether waterboarding or otherwise, will be decided in the courts, in front of a judge, after it’s fought out between the defense and the prosecution in these cases,” Hartmann said.

But just as it has taken years for the alleged Sept. 11 conspirators to be charged, there is no assurance the six will see the inside of a courtroom any time soon.

The law that tightened the tribunal process also bars detainees from legally challenging their imprisonment. But the Supreme Court is considering a challenge to that prohibition.

If the justices agree that legal claims from Guantanamo may be heard, attorneys for the six detainees may well go to court and try to head off a trial for their clients before they reach a military commission.

Times staff writer Josh Meyer contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.