Clerical errors and luck kept suspect in Lily Burk killing on the street, records show

- Share via

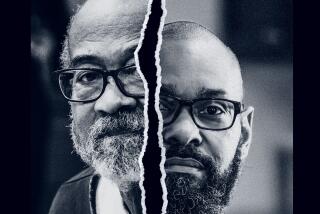

Three years before he was charged with kidnapping and murdering 17-year-old Lily Burk, Charles Samuel slipped through an unlocked side door of a Van Nuys home.

The man living there, James Alger, was dating Samuel’s ex-wife, according to court records newly obtained by The Times. As he spotted Samuel in his home, Alger confronted the intruder, asking why he had entered the house.

“I can do whatever . . . I want,” Samuel responded.

Samuel punched Alger two or three times in the face, leaving the victim bruised before Samuel snatched a cordless phone and keys and fled, according to a probation report released to The Times in response to an order from a court of appeals.

The report gives the clearest picture yet of the criminal record and recent biography of the man accused in the abduction and slaying of Burk, a high school student whose killing this summer jolted a city inured to news of violence.

Samuel’s criminal record stretches over three decades and includes mostly minor theft and drug crimes.

But the probation report shows that Samuel, 50, was also known to authorities as someone with a recent violent past.

This and other public law-enforcement and court records lay out how a combination of clerical errors, decisions by criminal justice officials and luck helped Samuel avoid a lengthy prison term that might otherwise have placed him behind bars on the day Burk was killed.

At the time of the June 30, 2006, Van Nuys attack, Samuel’s record included convictions for robbery and residential burglary in San Bernardino, making him subject to prosecution under the state’s tough three-strikes law. The law carries a 25-years-to-life prison term for third strikers.

Clerical error

But because of clerical errors that misstated Samuel’s criminal record, Los Angeles County prosecutors were unaware of his previous residential burglary conviction.

Even if prosecutors had known about Samuel’s two previous strikes, it is unclear whether they would have sought a life prison term. Under L.A. County Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley, prosecutors generally do not seek life sentences for repeat offenders unless the third strike involves a violent or serious crime, such as robbery.

In this case, the district attorney’s office charged Samuel with one felony -- petty theft with a prior -- and misdemeanor battery. Samuel pleaded no contest to the theft charge.

In her probation report, Deputy Probation Officer Paula Golden listed Samuel’s lengthy rap sheet and described his alleged break-in and attack on Alger as an “extremely serious offense.”

Samuel, she wrote, “is lucky that there were not more serious charges brought against him for his criminal behavior.”

A district attorney’s spokeswoman said in a statement that a “highly accomplished” prosecutor decided which charges to file but that it was “hard to reconstruct the rationale for a filing decision made several years ago.”

In an interview before he was sentenced in the Van Nuys case, Samuel told Golden that he had been unemployed since the 1970s and homeless for a year and a half, the report said. He had been separated from his wife since 2004, he said, and his two children lived with her mother. He denied using drugs.

Samuel told Golden that he agreed to plead no contest to the theft charge as part of a plea bargain to avoid a third strike. The report does not elaborate on the comment.

Samuel was sentenced to two years and eight months in prison and was released two years later.

Lily Burk

On July 24, Samuel was on parole for the Van Nuys incident and enrolled in a residential drug treatment program south of Koreatown when he obtained permission to leave the facility to visit a Department of Motor Vehicles office, even though the office was closed.

Burk went missing the same day while visiting Southwestern Law School in the Mid-Wilshire area as she ran an errand for her mother, a lawyer who teaches at the school.

Police said footage from surveillance cameras showed Samuel driving Burk’s car away from the area of the law school with the 17-year-old in the passenger seat. About 30 minutes later, another camera showed Samuel repeatedly and unsuccessfully trying to withdraw cash at a downtown ATM using a credit card, police said.

Burk made two calls to her parents that afternoon, asking how to use a credit card to withdraw money from an ATM. Her body was found the next morning in her Volvo in a downtown parking lot. Her head had been beaten and her neck slashed.

Samuel has pleaded not guilty to murder, kidnapping and other charges.

His previous strikes stem from the same crime -- one that bears a striking similarity to Burk’s abduction.

In 1986, he was accused of kidnapping an elderly man in San Bernardino and driving the man’s car to an ATM, where he demanded that the victim withdraw cash. Samuel allegedly beat the victim when no money appeared. Samuel pleaded guilty to robbery, residential burglary and car theft. He was sentenced to six years in prison.

Under the 1994 three-strikes law, prosecutors are allowed to charge any felony, however minor, as a third strike if a defendant has been convicted of two crimes considered violent or serious. Samuel’s robbery and residential burglary convictions count as strikes under the law.

But his rap sheet did not say that the 1986 case involved a residential burglary. Only residential burglaries are counted as strikes.

In 1997, Samuel was caught shoplifting a bottle of alcohol from a Barstow grocery store.

He was charged with a single felony: second-degree burglary. But prosecutors in San Bernardino County missed an opportunity to seek a life term for Samuel because they did not realize that he had two prior strikes.

Details about the robbery and residential burglary convictions were included in a probation report made public this year by a San Bernardino County judge at the request of The Times.

The newspaper made a similar request for a probation report in the 2006 Van Nuys attack. The Times argued in court papers that state law requires that a defendant’s old probation reports -- normally public for 60 days after a defendant is sentenced -- be made public again when the offender is charged with a new crime.

Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Patricia Schnegg denied The Times’ request but did not address the newspaper’s legal arguments.

The Times asked the California Court of Appeal to review the decision. An appeals court panel ordered the judge to release the report or explain her refusal to do so. Schnegg released the report Tuesday.

Allan Parachini, a spokesman for the L.A. County Superior Court, said he did not know whether the court, now dealing with a budget crunch, would change its policy to make such probation reports available to the public after the appellate court decision.

“The reality right now is that 100% of the attention of the judicial leadership is focused on the budget,” Parachini said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.