The NFL’s bully boys

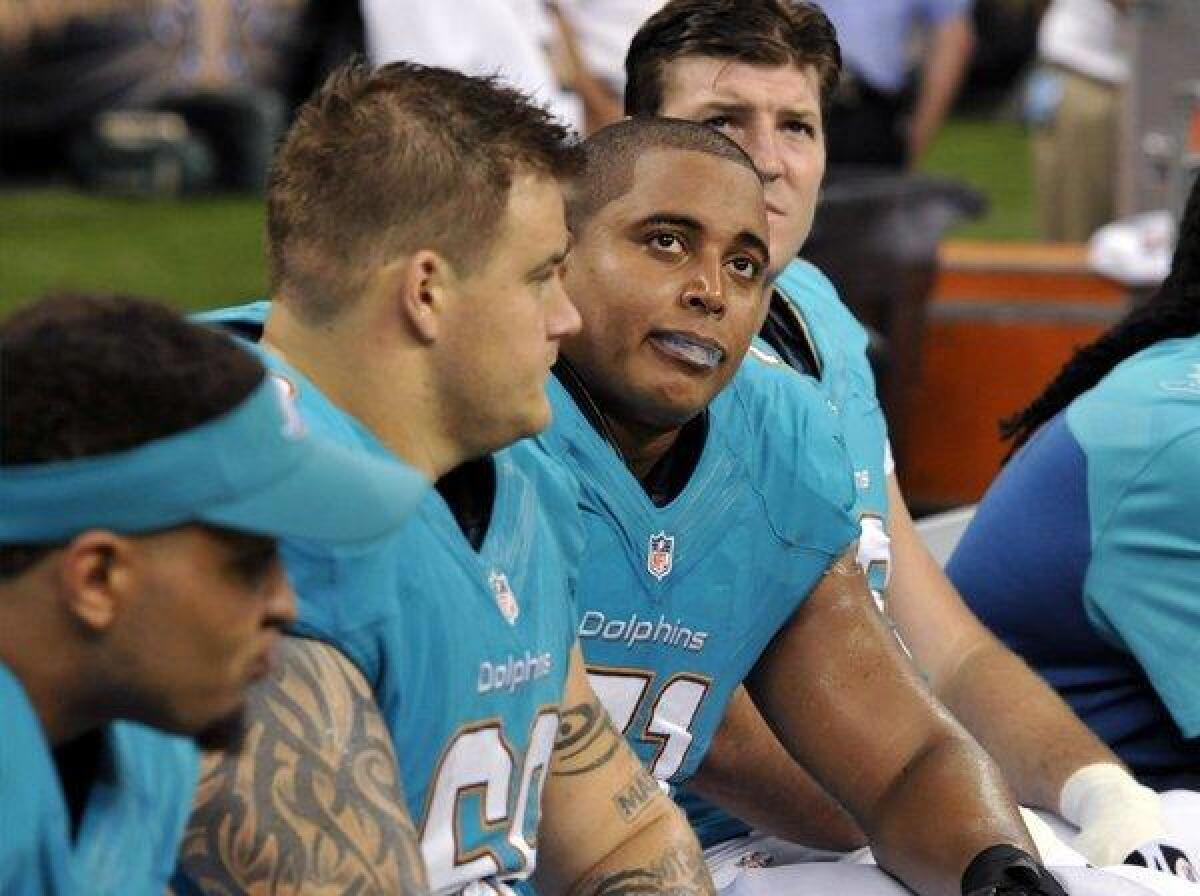

Miami Dolphins guard Richie Incognito (center left) and tackle Jonathan Martin (center right) sit on the bench in the second half of a game against the New Orleans Saints in September. Martin would later go on to accuse Incognito of bullying.

- Share via

So the secret is finally out: The National Football League is an anachronism. Not the game, which is as ever. But the league’s culture.

The NFL’s out-of-touch, out-of-time “context” has been on vivid display during the ongoing contretemps between Miami Dolphin guard Richie Incognito and his offensive tackle teammate Jonathan Martin. When Martin left the team complaining of an unsafe workplace environment due to harassment by Incognito and other Dolphins, he launched a national conversation about bullying, hazing, physical and verbal abuse, and athletes’ antics. But as important as these things may be — especially bullying — they are tangential to the deeper issue of the Incognito-Martin dust-up: the war to define what constitutes masculinity.

For generations, just about every boy growing up in America felt obliged to prove his manhood, which generally meant demonstrating physical strength, a disdain for gentility, a willingness and ability to stand up for himself, especially with his fists, and a disregard for anything “soft” — women, except as sex objects; intellectual prowess; and general sensitivity.

That’s how it was, right through adolescence and often beyond. Toughness is what made a man a man. No boy wanted to be called a “sissy” or a “wimp” or, worst of all, a “girl,” which is still a term of opprobrium used by some coaches to push their troops.

And that is the way it still is, apparently, in large parts of the NFL. That sort of manliness was on full display when, according to a Florida police report, Incognito allegedly used a golf club to touch the genital area of a female volunteer at a charity tournament and then rubbed himself against her; or when, as the head of a Dolphin Leadership Council, he held meetings at a strip club; or when he left a vicious, racist message on Martin’s voicemail. Incognito has defended himself by calling these episodes a “product of the environment,” and he is right.

But Incognito and many of his NFL brethren don’t seem to realize that they are living in a time warp. Just about everyone in the media, including the sports media, was scandalized by Incognito’s language — even after he protested that it was a joke and told a Fox Sports reporter that Martin used similar language with him — and just about everyone outside the NFL seems inclined toward defending Martin, which is how the bullying meme began.

That’s due in part to decades of feminist proselytizing but also to general civilizing forces that have deemphasized machismo and allowed men to define themselves in ways other than physical intimidation.

Martin is himself an example. He’s an offensive lineman who is the son of two Harvard-educated lawyers. He graduated from Harvard-Westlake School in L.A., and then Stanford. By all accounts, he loved football, but he didn’t love the muscle-flexing culture of the NFL. As his high school coach said — speaking of the cultural divide between Martin and others in the game — Martin was accustomed to Stanford, Duke and Rice players, not Nebraska, Miami and LSU players.

The old machismo, however, dies hard. Incognito’s teammates have leapt to his defense, and so have many others associated with the NFL, lambasting Martin in the bargain. A number of players called Martin a coward. One ex-Dolphins’ lineman, Lydon Murtha, said that Martin “broke the code,” adding that playing football was a “man’s job” and suggesting that the 312-pound Martin wasn’t up to it. New York Giants safety Antrel Rolle said that Martin should have punched Incognito in the face, presumably because that’s how men settle disputes.

Incognito himself is said to have felt betrayed by Martin because, he asserts, the racial slurs and abuse were intended as a form of “tough love.” Even several African American players on the Dolphins excused Incognito’s use of the “N-word” as just Incognito being Incognito. In effect, they were saying that machismo is thicker than race — though, of course, in defending Incognito, they were defending their own outdated machismo. What it all adds up to is an admission of this old-fashioned notion: How do you know you are a man if you don’t act like a goon?

The NFL is one of the last redoubts where goons and thugs have a privileged status. Two years ago the New Orleans Saints were punished for paying a bounty to players who incapacitated opposing players. Everyone admits that the violence of the sport, the danger and the hits, are a good part of the appeal of the league — our very own Hunger Games. Professional football allows its fans, and especially men who may feel culturally neutered, to reexperience the good old days when bravado and violence defined winners. Even cuddly John Madden, the former analyst, used to enthuse over what he called a “de-cleater” — a tackle that knocked a man off his feet.

So whatever else Jonathan Martin is the victim of, he has been preyed on by a form of ugly, vestigial, brutalizing masculinity. And he decided to resist it, not with his fists but with a legal process. That may not seem “manly,” but it is the way men do things nowadays — real men, that is.

Neal Gabler is a fellow at the Lear Center at USC. He is working on a biography of Edward M. Kennedy.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.