Cap-and-trade or a carbon tax: Which pain at the pump do you prefer?

- Share via

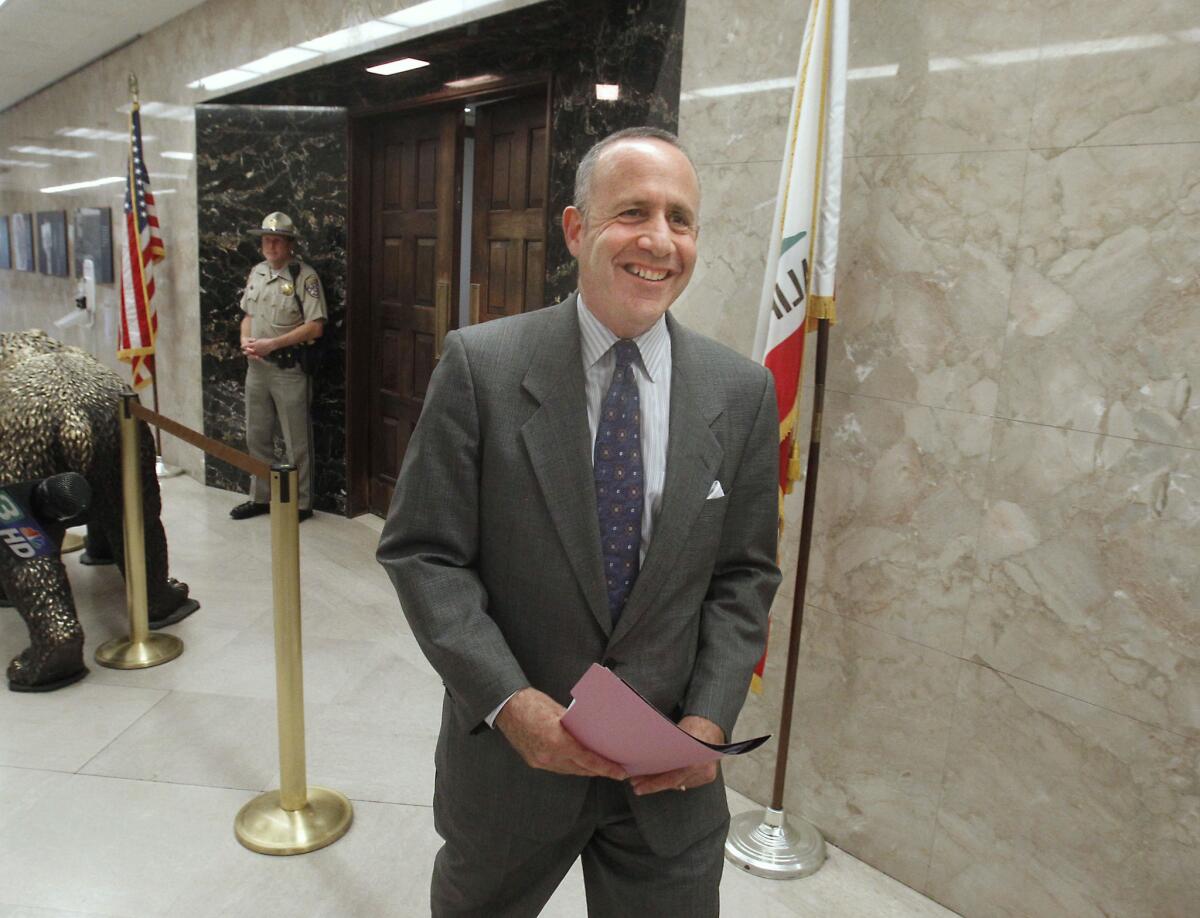

State Sen. Darrell Steinberg (D-Sacramento) is in his last year as a legislator, so it’s now or never for the carbon tax bill he outlined Thursday. Yet the proposal may have arrived one year too early.

Steinberg, the Senate president pro tem, wants to change the state’s approach to reducing carbon emissions from fuel. Under AB 32, the state’s landmark cap-and-trade law, oil companies must meet a gradually declining limit on emissions starting next Jan. 1 or buy credits from other companies whose carbon releases are below their caps. The cost of those credits is expected to add more than 12 cents a gallon to the price of gasoline, my colleague Mark Lifsher reported.

The plan Steinberg outlined would take oil companies out of the cap-and-trade system, requiring them instead to pay a carbon tax of 15 cents a gallon next year. Two-thirds of the money raised by the tax, which would increase to roughly 24 cents in 2020, would be doled out to California families earning less than $75,000. The rest would be used to support mass transit.

According to Steinberg, the tax would cost consumers less than the fees imposed on oil companies by the cap-and-trade law. But consumers haven’t encountered those fees yet; it’s all hypothetical at this point. If Sacramento approved Steinberg’s plan, drivers would blame the higher prices they see at the pump in January on the new carbon tax. On the other hand, if the carbon tax were imposed in 2016, drivers might not notice any change at the pump. That’s because prices already would have been raised to reflect the cap-and-trade fees imposed in 2015.

Even if there’s no apparent effect on prices, introducing a whole new type of tax is a politically dicey proposition. Voters fear that whatever the advertised purpose of the tax may be, lawmakers will eventually raise it to pay for other programs and services.

That’s why the best carbon-tax proposals don’t raise money for government at all. They return every dollar collected to residents in the form of rebates. They also pay an equal rebate to every resident, rather than basing the payment on the number of miles driven. That way, the tax encourages people to drive less in the hope of receiving more from the state than they paid in carbon taxes.

Steinberg’s proposal falls short of that ideal in a couple of respects. It would steer a third of the money to transit programs, and it would pay rebates only to low- and moderate-income households. Those provisions make the tax look more like an attempt to transfer wealth and less like an effort to reduce carbon emissions.

Critics on both the right and the left are already lining up against Steinberg’s plan, so it looks like the odds for passage are slim. And considering the broad opposition to new types of taxes, the odds would be slim even under the best of circumstances. Still, the public might be more receptive to the idea next year, after the cap-and-trade fees hit the gas pumps.

ALSO:

Daum: Belgium’s humane stance on dying kids

A costly pain in the neck, and what it says about healthcare

PHOTOS: Let’s celebrate some of America’s unsung heroes this Black History Month

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey and Google+

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.