Op-Ed: Privacy versus speech in the Hulk Hogan sex tape trial

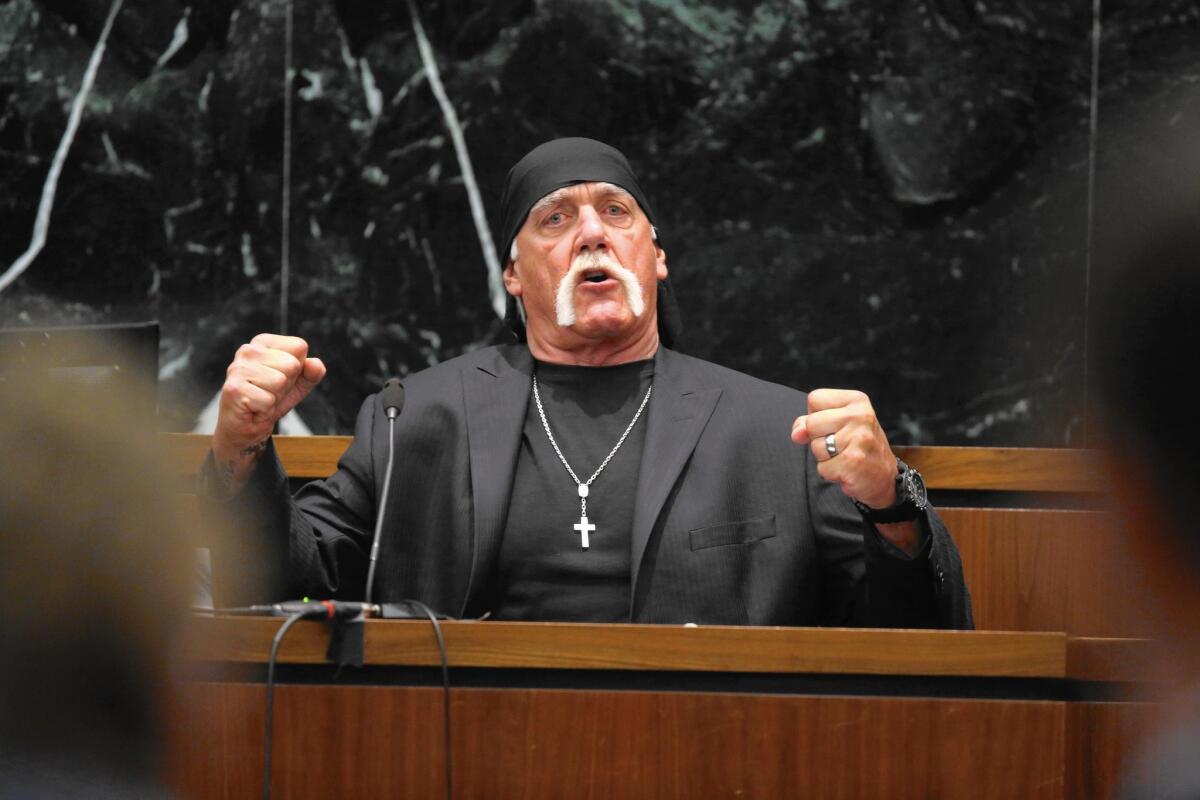

Hulk Hogan, whose given name is Terry Bollea, testifies in court on March 8, 2016, during his trial against Gawker Media in St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Share via

What’s newsworthy?

That’s the legal question at the heart of the Bollea vs. Gawker Media trial in St. Petersburg, Fla., which revolves around a videotape showing the wrestler Hulk Hogan, whose real name is Terry G. Bollea, having sex with the wife of a friend. Apparently, the friend, radio host Bubba “the Love Sponge” Clem, took the video without Bollea’s consent or knowledge. It’s all terribly salacious and, for many, terribly amusing; though Bollea obviously isn’t laughing along.

After the online news and gossip site Gawker posted an edited version of the sex tape, Bollea sued Gawker, its founder Nick Denton and its former editor-in-chief A.J. Daulerio for invasion of privacy. He’s seeking $100 million in damages. Gawker has raised the 1st Amendment as a defense and says that its action is constitutionally protected speech because Bollea is a public figure who has frequently discussed his sex life in books, interviews and his reality TV show.

So here we have high-minded constitutional principles running up against low fare.

Should juries assess newsworthiness according to the public’s actual interest in the material? Isn’t anything then newsworthy if enough people want to look at it?

The law allows recovery for publicly disclosing private information if the revelation would be offensive to a reasonable person and if the information is not “newsworthy.” Put another way, the facts disclosed must not be a matter of legitimate public concern.

But courts, including the Supreme Court, have failed to offer a definition or way of determining what is newsworthy. Defining the concept is problematic. Should juries assess newsworthiness according to the public’s actual interest in the material? Isn’t anything then newsworthy if enough people want to look at it? By this standard, the Hogan videotape is newsworthy simply because many people watched it and — logically — there is virtually no such thing as an invasion of privacy in a prurient society. (Sex, Daulerio readily conceded at trial, sells.)

Alternatively, should juries determine newsworthiness according to what the public should be interested in? But then who gets to decide what’s valid and what’s not? Who’s to say, in a democracy, that much of what fills the tabloids and periodicals at supermarket cash registers isn’t newsworthy, given that so many people are interested in gossip, particularly salacious gossip, about celebrities?

This is not a new issue, but it arises far more often now than in the past because of the Internet, which of course makes it possible to disseminate information — unfortunately including amateur pornography — to a mass audience quickly. Sex and the 1st Amendment are thus in constant contact.

On one side of the spectrum we have “revenge porn,” where a person posts, without consent, a sexually explicit video of a former lover. California and other states have adopted statutes making this a crime.

The Gawker case is more difficult because Bollea has never been media-shy and his past behavior suggests he believes his sex life is of interest to the public. In a 2006 interview with Clem, for instance, he boasted about the size of his appendage as openly as Donald Trump at a Republican debate.

Indeed, this case reflects how the changing notions of privacy in society make it much harder to decide what would be offensive to the reasonable person and what isn’t of public concern.

But juries, it’s said, make decisions based on emotion, on the gut. Accordingly, St. Petersburg jurors may ultimately find it hard to accept that Gawker’s speech rights reach into Bollea’s bedroom, notwithstanding the plaintiff’s lewd persona. There is a difference, after all, between talking about sex and watching it.

If the jury sides with Bollea, 1st Amendment absolutists will worry about the “chilling effect” the verdict may have on speech, and will claim it’s impossible to draw a line between permissible and impermissible expression. Speech is speech.

But I can imagine a clear rule: No videos of people having sex should be made public unless all of the participants consent. I think the media will survive the restriction.

Erwin Chemerinsky is dean and Raymond Pryke Professor of First Amendment Law at the UC Irvine School of Law.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.