Op-Ed: Being L.A.’s mayor is a political road to nowhere

- Share via

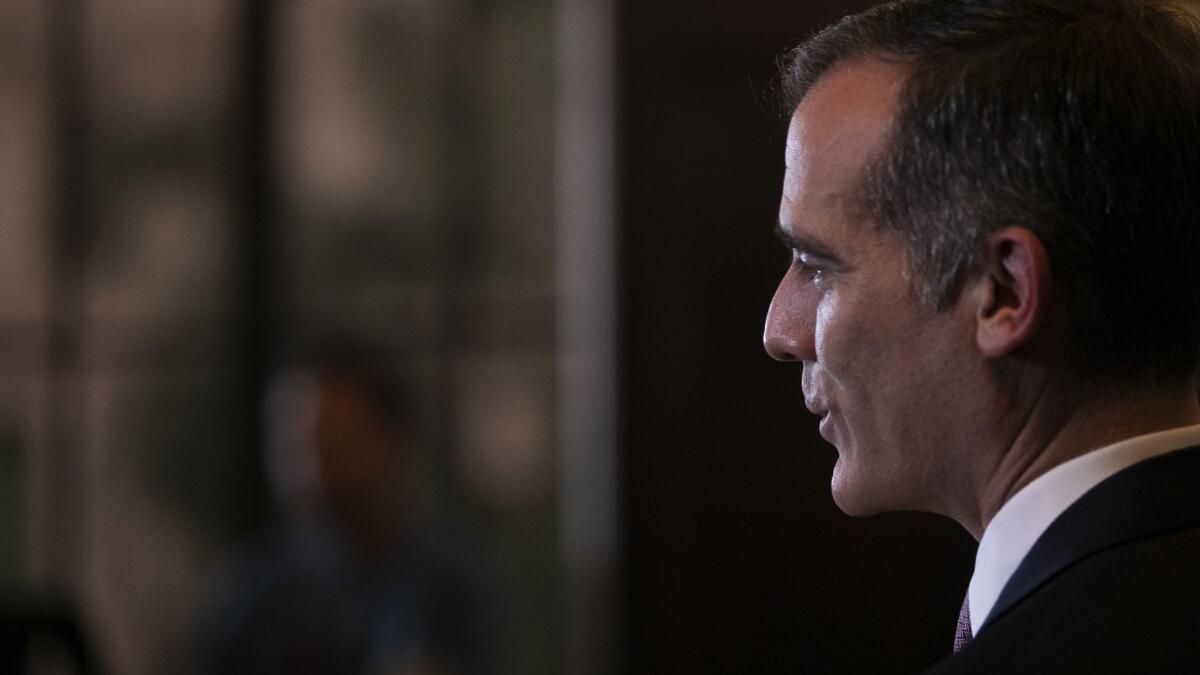

Five-and-a-half years after he first took the job, Eric Garcetti has discovered the downside of being mayor of Los Angeles: Politically, it’s a complete dead end.

After nearly 18 months of ostentatiously flirting with the notion of running for president — a flirtation that came complete with visits to such early primary and caucus states as South Carolina and Iowa — Garcetti announced Tuesday that he was abandoning the quest. There was plenty left to do in L.A., he noted, a sentiment with which no one could disagree.

A number of recent developments surely informed Garcetti’s decision. On the plus side, his mediation of the recent teachers’ strike heightened his national profile; on the minus side, it also dramatized the abysmal understaffing of L.A. schools. On the plus side, he’d won notices for his campaign to end L.A.’s homeless epidemic; on the minus side, the epidemic rages unchecked. On the plus side, the legislature had moved the California primary to very near the head of the list; on the minus side, Sen. Kamala Harris looks well on her way to becoming California’s favorite daughter when primary voters go to the polls.

No matter their ideology, mayors of Los Angeles don’t end up in higher office when they leave Spring Street.

But two higher and more enduring hurdles stood to thwart Garcetti’s dreams of hearing “Hail to the Chief” when he entered a room. First, mayors don’t become president (not unless they make the move from City Hall to the governor’s mansion first — and that hasn’t happened since Grover Cleveland). Second, mayors of Los Angeles rarely if ever move on to any higher office. Presiding over L.A. amounts to a death knell for all future political aspiration.

Consider: Tom Bradley, Richard Riordan and Antonio Villaraigosa all ran for governor and lost. Sam Yorty ran for president in the 1972 Democratic primaries and didn’t win a single delegate (though as a onetime leader of “Democrats for Nixon,” he might have suspected he didn’t have a lock on the nomination). Only one-term Mayor Jim Hahn seemed to understand the limited options that follow a career in City Hall: he happily subsided into a superior court judgeship.

This is a clear case of L.A. exceptionalism: mayors of other California cities have gone on to be governor. Democrat Gavin Newsom had first presided over San Francisco; Republican Pete Wilson had first presided over San Diego.

In California, a disproportionate number of statewide elected officials have come out of the Bay Area. Senators Harris, Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer are all San Franciscans (city or suburb), as was the elder Governor Brown and (the second time around) the younger. The difference here is largely one of civic culture: San Francisco, and San Diego, too, are cities where both elites and the media have paid more attention to local government than their L.A. counterparts. In Los Angeles, by contrast, local news coverage (particularly television) has focused more on the entertainment industry than on political leaders, while political elites — particularly the rich — have long been more swept up in national politics than local.

When Angelenos do advance to statewide office — like Ronald Reagan and Arnold Schwarzenegger — they’ve often come from Hollywood, not City Hall. As well, L.A. County is so vast and so divided — with 88 separate cities — that it’s hard for one local political figure to stand out. In New York and Chicago, by contrast, the mayor looms larger in public consciousness than in L.A.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

But that brings us to the other barrier to mayoral advancement — because mayors of Chicago and New York, their big-deal status notwithstanding, haven’t gone on to become governors or senators, much less presidents, either, as the Daleys, Rudy Giuliani, John Lindsay and Ed Koch could attest. (Michael Bloomberg is, of course, preparing to run for president, but there’s no way Democrats are about to anoint a New York billionaire to run against the New York billionaire already in the White House.) Mega-cities have always been such a distinct political terrain that presiding over them hasn’t struck suburban and rural voters as suitable preparation for governing a broader public.

And the politics of cities have seldom been as distinctive as they are today. Home chiefly to minorities, immigrants and millennials, America’s cities are moving well to the left of the rest of the country and, in some cases, their states. Last November, in otherwise solidly Republican states, Democratic candidates won upset congressional victories in Oklahoma City, Salt Lake City and Charleston, S.C.

No matter their ideology, however, mayors of Los Angeles don’t end up in higher office when they leave Spring Street. Alongside the seal of the city, the mayor’s office should have a Dante-esque inscription emblazoned on its doors: Abandon all hope for advancement, ye who enter here.

Harold Meyerson is executive editor of the American Prospect and a contributing writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.