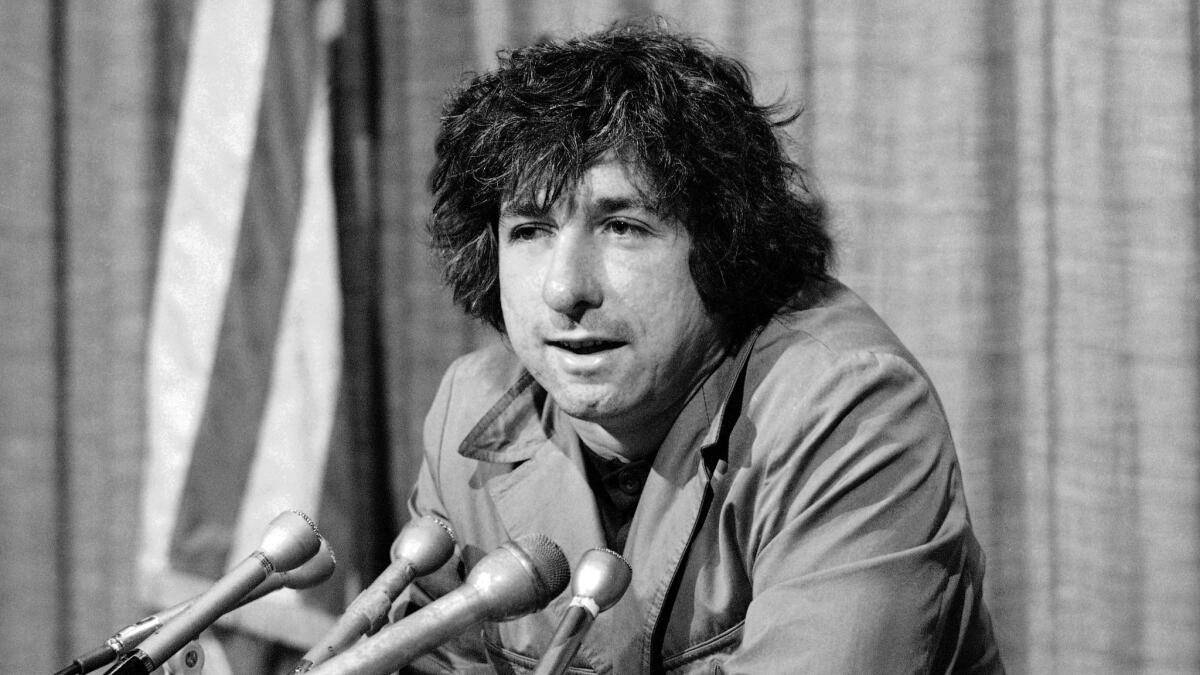

Op-Ed: Stanley Sheinbaum, Tom Hayden and the end of an L.A. leftist era

- Share via

It’s been an emotionally tough couple of months for the Los Angeles left. In September, Stanley Sheinbaum, anti-Vietnam War activist and faux-grumpy host of countless liberal gatherings, died in his Brentwood home at 96. On Sunday, Tom Hayden, author of the seminal document of the ’60s New Left, died in Santa Monica at 76.

For a number of years, Sheinbaum and Hayden lived about a mile from each other on L.A.’s Westside — Sheinbaum, to be sure, on a far ritzier street. (He was married to Betty Warner, daughter of one of the Warner brothers, and as that rare economist who actually knew how to play the markets, he substantially increased their wealth.) History won’t remember Sheinbaum and Hayden exclusively as Westsiders or Angelenos, however. Their commitments and causes were always more universal, even when they trained their attention on the problems at home.

In Los Angeles, Sheinbaum was for decades the chief financial supporter and on-call adviser to the local ACLU. In the wake of the Rodney King beating, then-Mayor Tom Bradley appointed Sheinbaum to head the city’s police commission, where he promoted some long overdue reforms and helped engineer the ouster of Daryl Gates — last in a line of L.A. police chiefs who saw their charge as brutally suppressing the city’s minority communities.

Each moved seamlessly from the local to the global; each sustained intense commitment while continually reevaluating strategies to fit a changing world.

But Sheinbaum was, fundamentally, a globetrotter without a portfolio, planning and participating in some of the first anti-Vietnam War teach-ins; negotiating the release of Greece’s once and future socialist prime minister from that nation’s military junta’s jails; and, in the late 1980s, assembling and leading a delegation of American Jews to meet with Yasser Arafat, inaugurating a process that culminated in the Oslo Accords.

Hayden will long be identified not with a place but a time — the ’60s, when he authored the Port Huron Statement and headed Students for a Democratic Society; went south as a civil rights activist; became a community organizer in the Newark ghetto; planned and led antiwar campaigns; led the demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago; and by dint of his writing, speeches and putting his body on the line, became the all-around personification of the steadily more radical New Left.

As that Left grew violent, however, Hayden recoiled, retreated (to a commune in Northern California) and recalibrated, organizing an emphatically nonviolent nationwide series of antiwar gatherings, part teach-in, part entertainment, that put pressure on Congress to end funding for the war.

Hayden was the writing, speaking and strategizing refutation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s adage that there are no second acts in American lives. As the fires of the ’60s were banked, he redirected his passion for social justice into mainstream politics, waging a primary challenge in 1976 to California Sen. John Tunney, a moderate Democrat.

In the wake of his defeat, Hayden and his then-wife, Jane Fonda, established the Campaign for Economic Democracy — a group of left activists who campaigned within the Democratic Party for environmental and economic reforms, advocating a shift to solar energy and winning rent control in a number of California cities. They also elected some of their own to state and local offices, most notably Hayden himself, who represented the Westside in the state Assembly and then the state Senate from 1982 through 2000. Hayden’s involvement, and CED’s, in state and local politics showed onetime antiwar activists across the country how to reengage with their country; many subsequently became community or union organizers or even elected officials.

Neither Sheinbaum nor Hayden was a man of the Old Left, but each fit the Old Marxist model of scholar-activist: Sheinbaum, a keen student of the global economy (it was he who told then Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton that George H.W. Bush was beatable because an early-’90s recession was in the works); Hayden, the author of 20 books, many of them reformulations of progressive purpose and strategy.

In a sense, each conducted through both word and deed a kind of decades-long tutorial for L.A. progressives. Each moved seamlessly from the local (Hayden even negotiating gang truces in South-Central) to the global; each sustained intense commitment while continually reevaluating strategies to fit a changing world. The city — and the world — were lucky to have them.

Harold Meyerson is executive editor of the American Prospect. He is a contributing writer to Opinion.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.