Op-Ed: How Watts and the LAPD make peace

- Share via

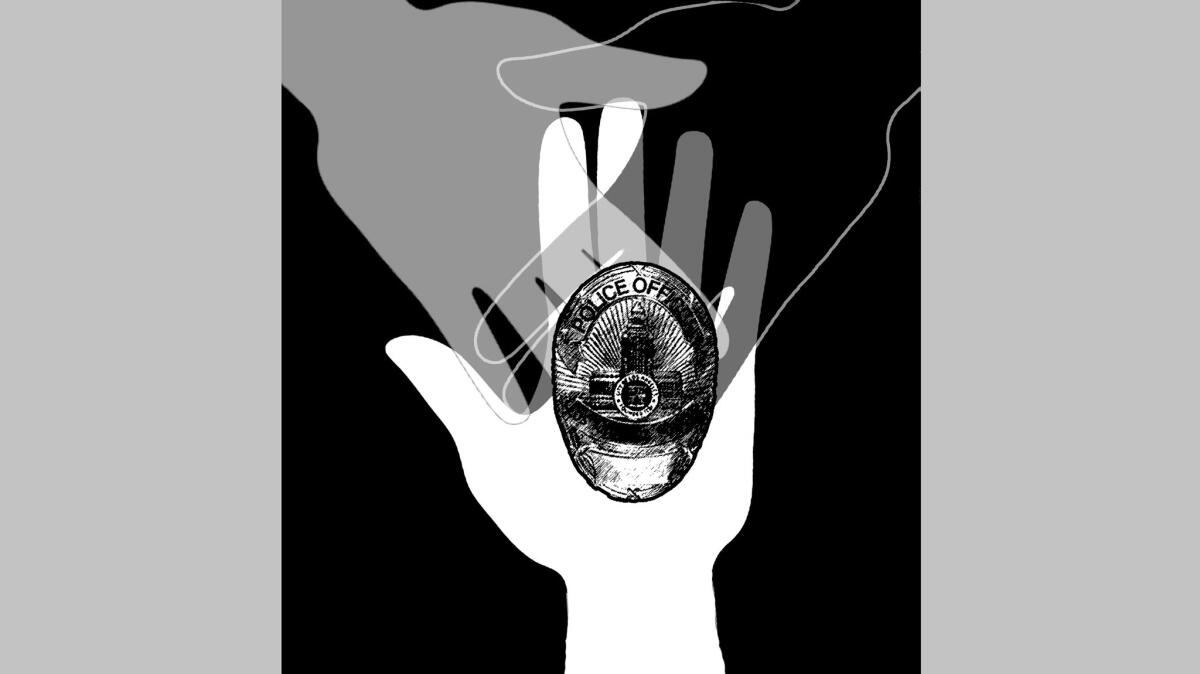

Police killings and resulting protests have sparked a national debate about the enmity among communities of color and the officers charged to serve and protect them. But in the South L.A. neighborhood of Watts, against all odds, police and residents have forged positive relationships that are lowering crime rates and creating a model that holds valuable lessons for other communities.

Many Angelenos think of Watts as the poverty-bound area that exploded 50 years ago in riots, or as the home of the quixotic Watts Towers. But the neighborhood has also given rise to the Watts Gang Task Force, a volunteer group of residents, police officers, community leaders, elected officials and representatives from local schools and nonprofits. Every Monday they meet in a windowless conference room to confront problems and avert violence in a way that would have been unimaginable a decade ago.

The task force was created in 2006 after a spate of violence that claimed seven lives. Its founders were Watts residents who had lost family members to violence, whose children were in gangs, or who had once been gang members themselves. They were tired of seeing young people die, and of police who didn’t seem to care. With then-City Councilwoman Janice Hahn providing the space, the residents met directly with law enforcement.

“There was a lot of anger coming out,” says Phil Tingirides, who became captain of the LAPD’s Southeast Station in 2007, “a lot of distrust and fear.”

But from those first tense meetings an effort evolved that is now largely credited with reducing shootings among youths in Watts by two-thirds, and with the near-eradication of homicides in its four public housing projects. It has changed the distrust-and-fear dynamic between the people and the police.

Each week, representatives from law enforcement report on crime and give updates on investigations in progress. Community problems are raised and resolved. The meetings have also become a clearinghouse of sorts, with the task force board — made up mostly of founding members — connecting residents, who often come looking for help, with resources right there in the room: employment training for men who are looking for work; a mobile medical program for parents to immunize their kids; grief counseling for a mother who’s just lost her child.

My organization has been part of the task force since 2007. I’ve seen firsthand what Watts and the LAPD have accomplished, and I am certain it can be replicated.

There are several key elements to the task force’s success. First, it’s community-driven. It was created by people who have a deep stake and sense of ownership in its work. “There’s a way you can build a relationship with your police department,” says Donny Joubert, vice president of the group and a longtime resident of Watts. “But the community has to demand it.”

Second, the police show respect for the residents, which began with the simple act of listening. “Phil started to feel the things that we were saying,” Joubert says. “He started to feel the pain.” The relationship grew to the point that Tingirides and his wife, LAPD Sgt. Emada Tingirides, would show up at the hospital, off duty, in the middle of the night, when neighborhood people had been shot. “Not because we were cops,” he says, “but because we were friends.”

This empathy led to a change in day-to-day policing practices in Watts, embodied by the Community Safety Partnership, or CSP, program — a collaboration between the LAPD and L.A.’s Housing Authority that places officers at the Watts public housing developments. CSP officers don’t just patrol the projects; they coach football, lead Girl Scout troops, attend health fairs and prayer services.

A few years ago, “the kids were just flat-out afraid of us,” says Emada Tingirides, who directs the program. Now, they swarm CSP cops, eager for a hug or high-five. Some of these officers, including Tingirides, grew up in Watts. Others meet with local residents during their training. These officers aren’t just policing the community; they’ve become a part of it.

And that affects how they respond in tense situations. Several months ago, a young boy wielding what looked like a 9-millimeter gun ran toward a group of cops in the Nickerson Gardens development. A similar situation in Cleveland in November led to police killing 12-year-old Tamir Rice. But at Nickerson Gardens, Joubert says, the police “didn’t reach for their guns, didn’t flinch, not even one time.” They recognized the gun was a toy; because they knew and mentored so many boys in the neighborhood, they didn’t assume this one had violence in mind. “If it had been regular police,” Joubert observed, “it would have been a whole different story.”

The incident didn’t stop there. Joubert went to nearby merchants, including ice cream truck drivers, and persuaded them to stop selling toy guns.

This speaks to another element of the success story in Watts. There is mutual accountability between the police and resident leaders — expectations they have of one another, and of themselves that are maintained and reinforced by the weekly task force meetings.

“We set a tone for how police work’s going to be done in this division,” says Phil Tingirides, who was recently promoted to commander of South Bureau, which includes Watts. Joubert adds that the community must “be willing to step up” before its own. He and other leaders send pot-smoking men and pimps away from schoolyards; insist that parents keep track of their kids’ activities in the dangerous after-school hours; set clear expectations of teens in youth employment programs. Residents share information with police — about drug hot spots, weapons caches, rumored gang retaliations — which requires a level of courage outsiders can’t fathom. “That takes a lot of power away from gangs,” says Tingirides, “when they can’t count on silence from fear.”

Like any genuine relationship, the one between law enforcement and Watts residents requires work, time and commitment. Tensions flared in March after a fatal, unsolved shooting in Jordan Downs, the first in nearly four years, but both sides have stayed at the table. Police officials nationwide — and in the rest of Los Angeles — would be wise to take notice. In the place where the nation’s most famous civil unrest was sparked by a police stop gone bad, the LAPD and the community have joined forces, calmed a neighborhood and saved lives. If this kind of transformation can happen in Watts, it can happen anywhere.

Nina Revoyr is the executive vice president and chief operating officer of Children’s Institute Inc. and the author of several novels, including “Southland.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.