Op-Ed: One doctor’s patient of the year

- Share via

End-of-year lists abound. Standout movies. The most memorable books. Yet I’ve never seen a doctor publish a “top 10” or recognize a practice’s patient of the year. Not that we lack material. The average primary-care physician follows the health of about 2,000 people. Over a year, that’s enough to view the full spectrum of life’s calamities and triumphs. Despite our best efforts, some patients experience a bad-news bolt from the blue. Others overcome every obstacle posed by a seemingly malevolent fate. Dramatic though they may be, the stories usually remain in the exam room, as perhaps they should. Occasionally though, a tale demands to be told. Amid this year’s welter of joy and suffering, my patient Monica’s story stands out.

I had not seen Monica for some years while she was treated for breast cancer. Her cancer proved difficult to cure. She had undergone bilateral mastectomies and many rounds of chemotherapy. She scheduled an appointment with me, her primary-care doctor, primarily to allay her husband’s concerns about overlooking health issues beyond her cancer.

Monica mostly needed someone to talk to. An accomplished woman, she recounted how the illness struck her just when she was offered a job that would have moved her to another level in her profession. Her prospective employer kept the position open in anticipation of her recovery. The duration of her treatment proved unexpectedly long and nixed the opportunity.

Practicing in “body beautiful” Los Angeles, the land of the nips and tucks, we need to be particularly careful not to reinforce social stereotypes.

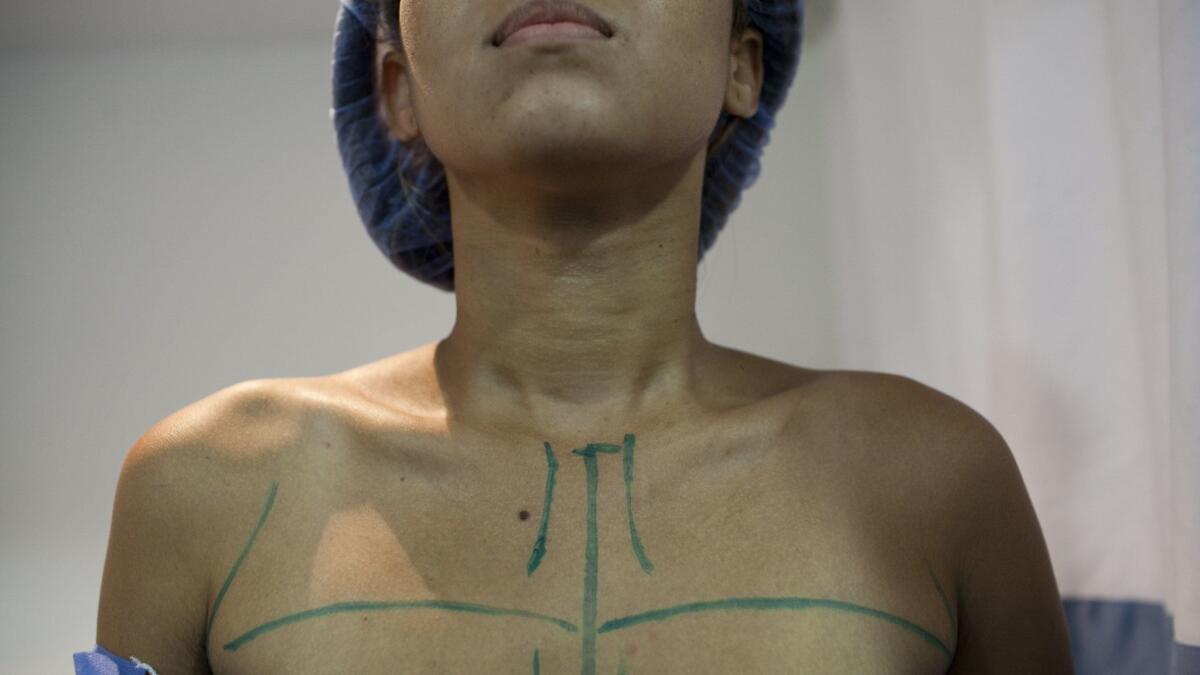

Now Monica faced a decision on breast reconstruction. After many months of treatment, the prospect appeared daunting. She would need surgical placement of tissue expanders to create room to allow yet another surgery to place implants. The whole process would mean more doctor visits, hospital time, surgical risks and the chance of infection. Choosing additional treatment just as her recovery stabilized felt wrong to her.

Monica’s oncologist had referred her to an accomplished plastic surgeon with the comment that she might not want to be “disfigured” forever. When she used the doctor’s word, I felt a surge of emotion that rarely occurs when I see patients. Disfigured? Yes, Monica’s breasts were gone, but the fine work of the surgeon left her symmetrical and far from disfigured. Monica’s husband told her not to have the surgery for him. The week prior to her visit, he had broken down in my exam room, describing Monica’s treatments and his concerns for her long-term health. In a year that has revealed so much disrespect and bullying directed against women, his reaction offered a dramatic reminder that men can be steadfast partners through life’s most adverse circumstances.

I told Monica what she surely already knew: She could make the best decision for herself. In my experience, reconstruction is critical for many breast cancer patients. It allows them to take a much needed step to restore their body and self-image. No doubt, that knowledge was also behind the comments from Monica’s oncologist. But Monica was not “many patients.” She had the emotional strength to resist conventional thinking. She could weigh whether additional surgery and the burden of treatment made sense. In any case, the notion that she was suffering from disfigurement was absurd. Ten minutes with Monica and anyone would see she’s a vibrant and intelligent woman engaged in her life, ready to continue her career, connected to her husband and a full participant in the lives of their children. She has no need to satisfy others’ expectations.

The oncologists and plastic surgeons I work with perform miracles. Still, healthcare providers sometimes benefit from a reminder that we serve patients, not vice versa. Practicing in “body beautiful” Los Angeles, the land of the nips and tucks, we need to be particularly careful not to reinforce social stereotypes. Monica made the choice to say “no,” or at least “not now.”

After nearly 30 years in clinical practice, seeing such strength in the wake of life-threatening illness still inspires. Monica’s character defines the term “healthy cancer patient.” She is my patient of the year for 2017.

Daniel J. Stone is an internal medicine and geriatric medicine specialist in Los Angeles.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.