Opinion: If Brazil cares about its legacy, it won’t silence World Cup protesters

- Share via

Brazilian officials want the world to believe that there’s nothing extraordinary about the strikes and protests that have vexed the country in the year leading up to the 2014 World Cup.

“I would say it’s almost natural,” said Deputy Minister of Sport Luis Fernandes on a recent call with international media. “Pressure groups understand that this is also an opportunity to make their demands be voiced globally, so we have to deal with that.”

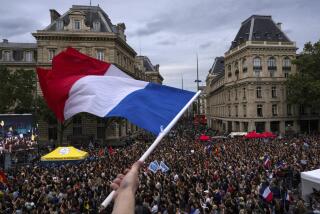

Dealing with that has earned Brazil a cautionary yellow card from Amnesty International in the wake of numerous reports of police violence against protesters and journalists since the Confederations Cup last summer — a warm-up for this summer’s World Cup that sparked demonstrations nationwide. In the months following, protesters took to the streets in historic numbers, from students airing grievances about FIFA imperialism and wasteful World Cup spending, to public-sector employees on strike for better wages and working conditions, to black bloc anarchists lighting fires.

The chaotic vibes have threatened to spoil what was hoped to be a giant coming-out party for Brazil. Though an array of protesters have taken to the streets in recent months, the unrest is largely the consequence of poor communications about the costs and benefits of the World Cup, according to Fernandes and others in the government.

“I think basically we thought that the benefits were evident and that the World Cup addresses our main sport, so that support and understanding of the benefits would be almost automatic,” Fernandes said.

Brazilians! Soccer! What could go wrong?

As it turns out, the benefits of hosting the World Cup were mostly evident to the Brazilian elites using the public coffers like an ATM machine. For many other Brazilians, the World Cup has come to represent unfulfilled promises, brutal evictions and the transfer of public spaces to private hands. At times the rumble in the streets has overshadowed the action on the pitch, like when police fired rubber bullets and tear gas outside Maracana Stadium as fans watched a match inside.

The swelling frustration creates what Fernandes calls “paradoxes of our development efforts.” In Manaus, for example, protesters will be able to organize more effectively by taking advantage of broadband improvements that have connected the Amazon region to the rest of the country in unprecedented ways.

Now, FIFA and local officials are scrambling to finish stadiums in time for this week’s opening match in Sao Paulo, where an ongoing strike of subway workers has courts raising yellow cards of their own, ruling that labor disputes at this critical time are an abuse of power. Meanwhile, across the country, unfinished transportation, energy and telecommunication projects are drawing scrutiny from hordes of Twitter-happy foreign media.

“We have to think legacy,” said Fernandes of the delayed projects, now rebranded as long-term projects. “We have to think beyond the World Cup.”

The Ministry of Sport claims that investment in all of the World Cup stadiums amounts to less than 1% of what the national government has spent on health and education over the last four years, not including state and municipal spending. Development has been a historical challenge for Brazil, Fernandes said. “It won’t be solved by one World Cup or one Olympic Games. It’s a continued effort of various generations.”

For many Brazilians of this generation, development means testing the limits of their young democracy. In the last decade, the wealthiest Brazilians have reaped the rewards of globalization and millions have emerged from poverty thanks to widespread federal assistance programs, yet the poor are still subject to forced evictions, military occupations and police brutality, while Brazilians from all walks of life struggle against the historical headwinds of corruption and inflation.

There is an underlying hope among government and FIFA officials that everyone will just chill out and enjoy the party, but that doesn’t seem to be happening. Even the beloved Brazilian national team has been the target of small but passionate protests. If the team falters and protests regain steam, authorities could have their hands full.

After last June’s protest, Brazilian police and military have received training to help avoid bloody conflicts in the street, yet the riot gear, tear gas and rubber bullets — and a dash of 21st century drone technology — echo the oppressive military regime that kept a tight lid on dissent from 1964 to 1985. Over the next several weeks, how the government chooses to deploy its nearly $1 billion security apparatus is vital to how the world sees Brazil — and how Brazil sees itself.

At this point, it’s clear that the country’s World Cup legacy won’t be one of flawless stadiums and economic miracles. And even though the Brazilian national team is favored to win the tournament, a sixth trophy is no sure thing. Yet whether foreign visitors have 4G cell service or a timely train is secondary to whether Brazilians have the right to peacefully assemble.

In that sense, the most lasting legacy of Brazil’s World Cup hinges on freedom of expression. Instead of resorting to security policies that hearken back to the country’s most oppressive eras, Brazilian officials need to show the world that even if the stadiums are unfinished, the people’s voice is loud and clear.

Chris Feliciano Arnold is a recipient of a 2014 Literature Fellowship from the National Endowment of the Arts. He has written essays and journalism for the Atlantic, Salon, the Millions, the Rumpus and Los Angeles Review of Books. Follow him on Twitter @chrisarnold.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.